For many seasonal sailors, the winterizing routine is already well underway. But there are more than a few diehard sailors in the mid-Atlantic regions, on the West Coast, and even in New England, who plan to spend all or part of the snowy season afloat. Some, we daresay, look forward to the quiet of winter. If youre toying with the idea of keeping your boat in the water during the winter, heres a short rundown on some of the more important steps to take.

Many of these steps can be delayed until temperature lows are in the mid-20s-a little early frost doesn’t generally matter. Liveaboards-those who will be using the heater every day-can skip many of the steps. They can also install a semi-permanent winter cover or shrink wrap to ward off snow and ice, but the aim of this report is to keep you sailing through the winter.

The online version of this article includes links to several related tests and blog posts that provide further guidance on making your winter more enjoyable-whether you plan to stay afloat or not.

Winterizing systems

Scrub and pump out the potable water tank. A light once over with a brush, without any cleaner, is enough if its done annually. Rinse and vacuum out the remains with a shop vac and leave the tank cover off. If you lay the tank up clean and dry, it will be fresh and ready to fill in the spring.

Downstream of the water tank but upstream of the pressure pump, add a shutoff valve followed by a diverter T. Add a second valve on the diverter T and a length of half-inch ID hose. Remove any carbon water filters and replace the water-filter cover. Draw -50-degree burst point propylene glycol antifreeze mixture into all of the lines using the pressure pump, opening the taps one at a time (hot and cold) and letting them run. Let the clear water go down the drain until its as pink as the feed, then shut off the faucet. Test the blend with a refractometer and save some of the weak stuff; it will be useful for flushing the head in mid-winter. When finished, remove the suction hose from the antifreeze container and blow out the lines with the pump by letting it run dry for about 10 seconds per tap. (The glycol lubricates the pump, so it will not be damaged.) If you have a tank water heater, you should drain it and bypass it.

Don’t leave the glycol in the system any longer than needed. Glycol is biodegradable and can turn into a nasty soup of bacteria and yeast if left in place in warm weather. Ethanol antifreeze is even more vulnerable to this.

Dont winterize with weak glycol. Not only is freezing possible, but a nasty water system is a common result. If the anti-freeze solution is more than 25-percent glycol, bacteria and yeast cannot grow; at lesser concentrations, they thrive.

Be careful which glycol you use. Potable systems call for food-grade propylene glycol, but this can harm neoprene and clear strainers. Flushing and draining the potable water system may be your best option. Black water and engines should be winterized with ethylene glycol, which is less harmful to neoprene parts. In our view, there is no environmental preference for either propylene glycol (the pink stuff) or ethylene glycol (ordinary antifreeze). Both are essentially non-toxic to fish and are easily treated at the sewage treatment plant.

Pump out the holding tank. The head will be flushed with a jug of ethylene glycol for the rest of the winter. If the boat is kept in the water, this can safely be diluted to about 20-percent glycol; the water moderates the temperature, and the tank will not go far below freezing. While youre at it, give some thought to where you will pump out mid-winter, when most of the pumpout stations and services are shut down.

Pull the top off the head-pump mechanism, lubricate the piston, and pour glycol into the chamber. Alternatively, install valves in the head intake to allow winterizing, similar to the way potable systems are winterized. (See Fighting Off the Big Freeze. top right)

Keep the gasoline or diesel tank full. This is particularly important in the spring, when the water will be cold but the air warm and humid, drawing water into the tank. Alternatively, install a silica-gel vent filter in the system. (See PS January 2013 and January 2014 online.)

If you use your outboard every few weeks, it requires no winterization other than tipping it up out of the water. The engine will drain and antifreeze is not required. There is no need to run the engine out of fuel, or to fog the cylinders, if a good anti-corrosion additive is used. (See E-10 Fuel Additives That Fight Corrosion, PS August 2012 online.)

Inboard engines also require attention, but how much depends on the climate and fuel system design. Diesel can begin to gel at 15 degrees below zero. In the lower 48 states, its rare that your fuel will actually get this cold, but your diesel tanks might still benefit from an anti-gel treatment. If youre expecting arctic temperatures, talk with your engine manufacturer and local mariners about recommended measures.

Your bilge pumps should have no loops or check valves. Any water must be free to drain back to the sump, and this should remain ice-free as long as the boat is in the water. If any water remains in the line, it will freeze and the pump will not function.

Adding warmth

Replace most port and hatch screens with a piece of 1/8-inch acrylic or Lexan cut to fit. This adds considerable warmth to the cabin and prevents condensation. (See DIY Fixes to Beat the Cold, PS December 2015 online.)

Window covers also add warmth downbelow, whether external (canvas or rigid) or internal (drapes or blinds). Be sure to remove any outside covers on sunny days to benefit from the radiation. A bank of large windows and hatches can contribute as much as 500 BTUs per hour on a sunny day.

There are a variety of ways to insulate doors and windows. The aim is to add both insulation and draft control, in ways that don’t impair access. On one Chesapeake-based PS test boat, we use closed-cell foam attached to the door with Velcro, but weve also seen beautiful quilted covers. Even a simple draped beach towel helps.

Heaters that release combustion products into the cabin, no matter how clean they seem, don’t belong on board. They add moisture to the cabin, require continuous venting, and are utterly unsafe for sleeping. Install CO and CO2 detectors, but bear in mind that detector failures are common. They should be replaced every few years. Electric heat is fine while at a dock, but portable heaters also have their hazards.

Snow Risks

Storing your tender on davits during the winter is a risk, even when its covered. The tender will deflate in the cold, and should it blow off in a storm, the combination of snowfall and ice blocking the drains can make it extremely heavy. If you insist on keeping the dinghy on davits, tricing lines, crisscrossed under the tender, can help support and distribute any added load.

Deep snow presents unexpected scenarios. A fuel fill that is normally well-drained may be submerged. Cockpit lockers that are normally exposed only to splashes may be in standing water after the cockpit drains plug with ice (a common scenario on boats that are left untended). Since the deck will not warm with the sun, condensation will get worse. A dodger helps keep the companionway clear. Finally, although the weight of the snow itself is not damaging, a boat can sink 3 to 6 inches below its standard waterline due to snow cover, pushing water up the exhausts and through low cockpit drains. Can your boat manage this waterline change (or worse) without flooding? A collapsible plastic shovel is a big help for clearing decks and cockpits.

In high-snow areas, liveaboards will need to add extensions to prevent the smokestack vent from becoming blocked by accumulated snow.

Do not roll soft-vinyl windows when temps dip below 50 degrees; cracking is likely.

Luke-warm water works for melting ice from frozen drains and stuck lockers without a risk of cracking; avoid chipping or force in cold temperatures since plastics become brittle. Also, if the temperature is above freezing, the salt in seawater helps clear frost from decks.

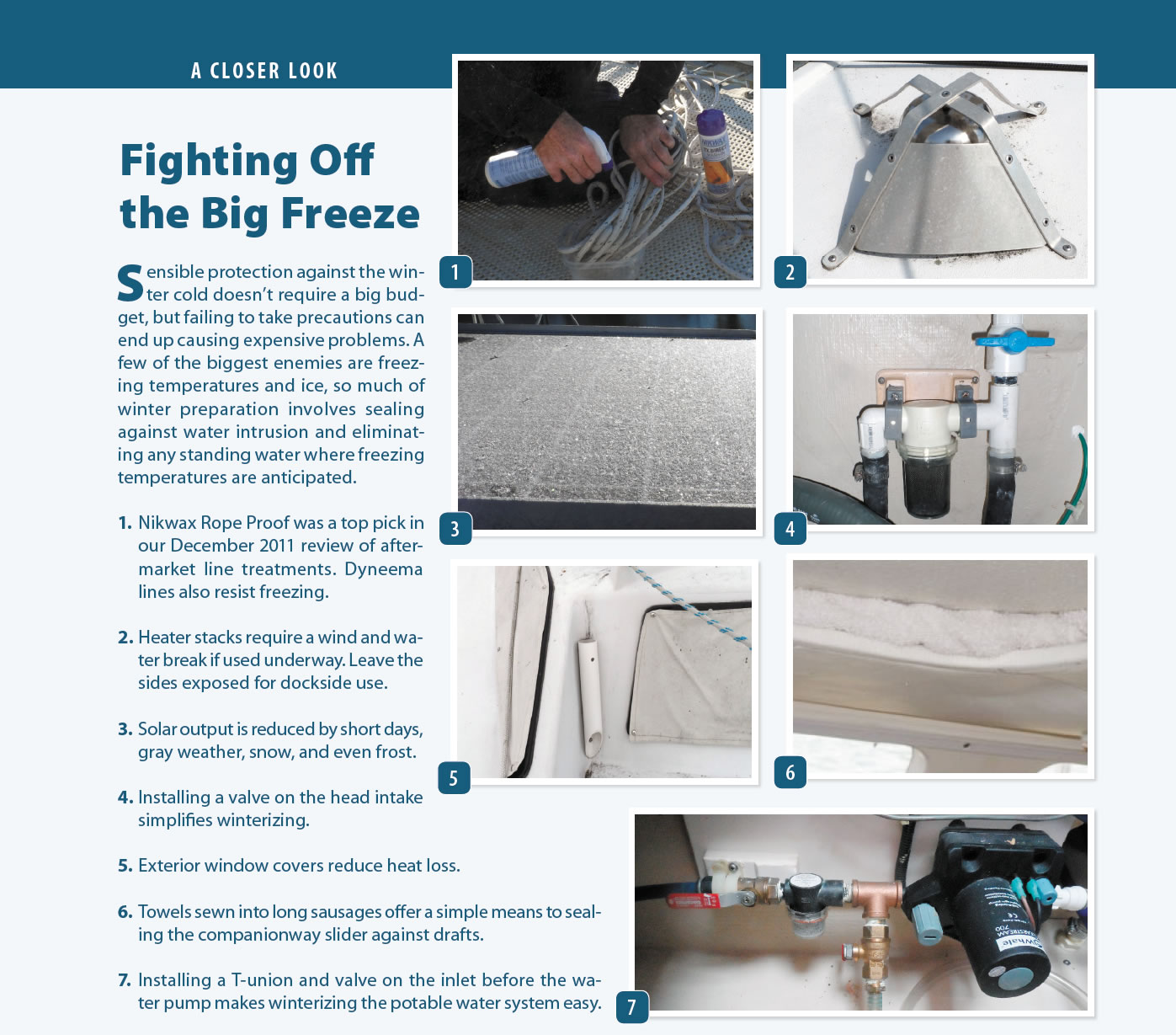

Sensible protection against the winter cold doesn’t require a big budget, but failing to take precautions can end up causing expensive problems. A few of the biggest enemies are freezing temperatures and ice, so much of winter preparation involves sealing against water intrusion and eliminating any standing water where freezing temperatures are anticipated.

1. Nikwax Rope Proof was a top pick in our December 2011 review of after-market line treatments. Dyneema lines also resist freezing.

2. Heater stacks require a wind and water break if used underway. Leave the sides exposed for dockside use.

3. Solar output is reduced by short days, gray weather, snow, and even frost.

4. Installing a valve on the head intake simplifies winterizing.

5. Exterior window covers reduce heat loss.

6. Towels sewn into long sausages offer a simple means to sealing the companionway slider against drafts.

7. Installing a T-union and valve on the inlet before the water pump makes winterizing the potable water system easy.

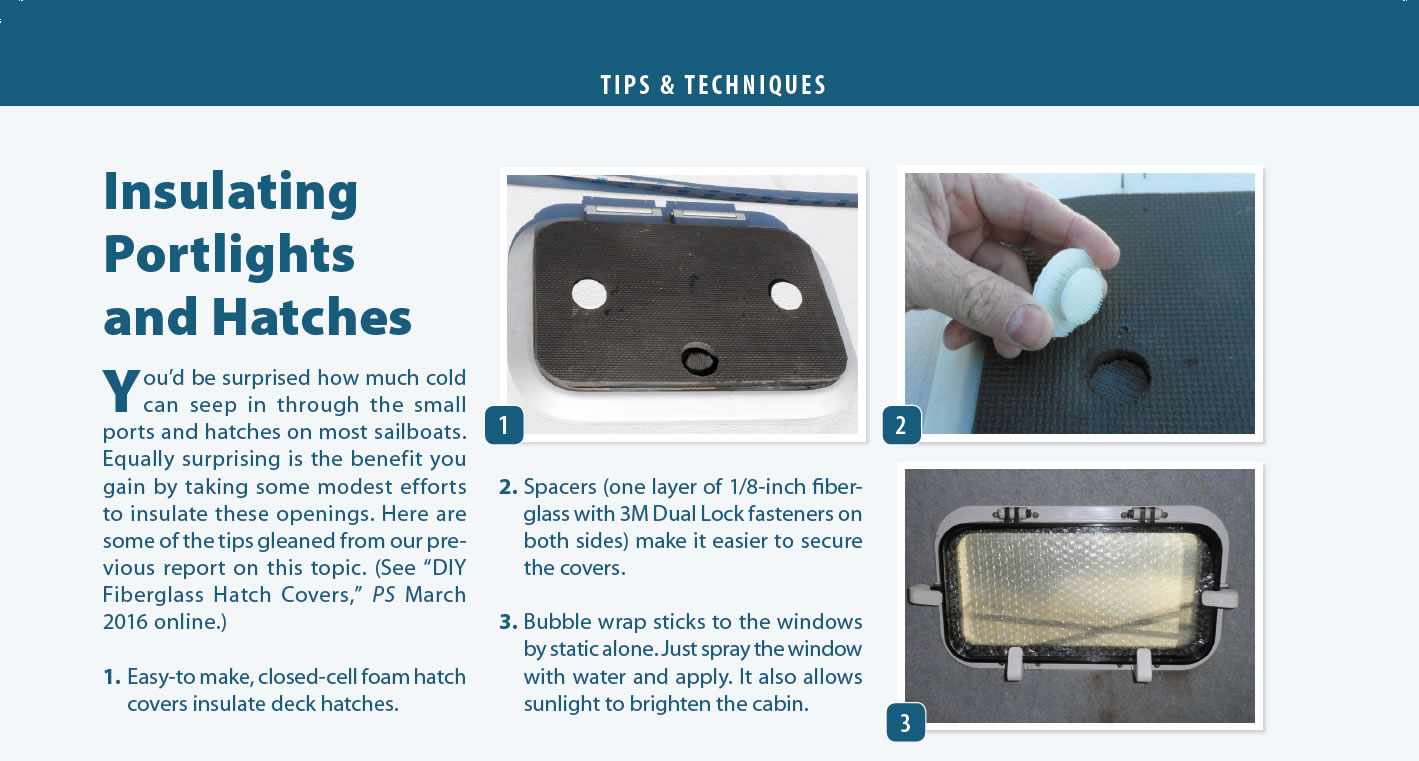

You’d be surprised how much cold can seep in through the small ports and hatches on most sailboats. Equally surprising is the benefit you gain by taking some modest efforts to insulate these openings. Here are some of the tips gleaned from our previous report on this topic. (See “DIY Fiberglass Hatch Covers,” PS March 2016 online.)

1. Easy-to make, closed-cell foam hatch covers insulate deck hatches.

2. Spacers (one layer of 1/8-inch fiberglass with 3M Dual Lock fasteners on both sides) make it easier to secure the covers.

3. Bubble wrap sticks to the windows by static alone. Just spray the window with water and apply. It also allows sunlight to brighten the cabin.

Thanks for sharing this informative article, I definitely enjoyed reading it, you may be a great author.

Diesel begins to gel at 15F ABOVE zero, 15F below freezing. At these temperatures you will need an icebreaker to move your boat.

Thanks for this article. My vessel is a damp and year-round cool environment that never experiences freezing. Low temperatures rarely dip below +2 degrees C. To control mold, I have had good results using a humidistat at at 60% RH to power an oil-filled electric heater year-round. I caution against using electric heaters with integrated fans. If the fan fails, the only protection against a heater melt-down and potential fire is a thermal fuse link in the heater that may or may not work. Also, any heater with an electronic control, as opposed to a simple thermostatic switch, may reset the first time power is interrupted making the heater nonresilient to a power interruption and making a humidistat unusable. I set the thermostat at 25 degrees C (77 F) as a maximum temperature and let the humidistat control the heater, thus allowing the temperature to follow the humidity, saving money on shore power on cold but dry days.

For portlights and hatches we find that refectix makes a huge difference in heat loss. We cover them when the sun goes down and you can immediately feel the difference.

We also use them on the sunny side of the boat on really hot days.