Solid fiberglass is strong and durable, but it weighs a ton. Even boats with solid hulls generally have cored decks, cabins, stringers, and bulkheads. By constructing a boat using sandwiches of resin, fiber, and core materials, we can improve both performance and stability, while maintaining durability, but only if we’re smart about it. In October 2007 (“Core Issues in Hull Construction”) we presented an overview of core materials, discussing strengths, weaknesses, and construction methods. Here we focus on a unique product that combines the best structural properties of plywood and balsa with the rot resistance of foam.

Observations

We’ve used a variety of foam, balsa, and plywood cores in our boats and used all of them during repairs. For any do-it-yourselfer, it’s important to recognize that each has a place and a few quirks regarding proper use.

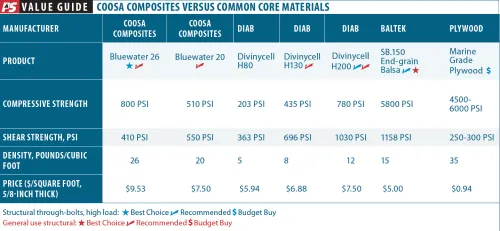

For instance, it’s important to know what forces the panel will be subject to—compressive or shear. Compressive strength resists crushing under fasteners and denting. Shear strength prevents failure caused by flexing across a panel. Not all panels are best suited for each of these forces.

Plywood

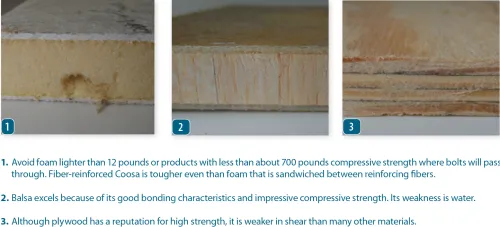

Plywood is the low-cost option, it has high compressive strength and provides some stiffness, but its low shear strength reduces its efficiency as a composite sandwich component. If a leak in the bedding or coating occurs, water wicks rapidly along the grain, spreading rot. Unlike other cores, it will hold screws, but this is the worst thing you can do, since it nearly guarantees water will eventually sneak inside.

Bottom line: Plywood is the penny-pincher’s solution.

Balsa

The stories of hidden rot in a cored hull or deck make some sailors nervous about balsa core, and we’ve dug out our share of rotten balsa. But the cause was almost always poor sealing of fasteners, and in some cases, poor construction practices —i.e. poor wet-out that leaves core kerfs unfilled, or a failure to seal holes or replace balsa with solid laminate where though-deck hardware is mounted.

On the plus side, balsa has superior compressive strength and good shear strength, making for exceptionally strong, light, and fatigue-resistant structures. It is the easiest core material to bond and is one of the most rugged if you can keep it dry. Minor leaks are not as immediately fatal as with plywood because the vertical cell structure resists lateral water migration.

Bottom line: Structurally top notch, and durable if you to pay attention to sealing details where fittings attach.

Foam

Foam won’t rot. But that doesn’t mean it can’t delaminate. Most types do not bond as well as balsa. If water gets between the layers, freeze and thaw cycling can reduce large areas of foam core to mush in just a few years. Low density foam has low shear strength; it is vulnerable to denting and requires oversized backing plates. The shear strength is low, so excessive flexing loads should be avoided. High density foam improves on these properties, but never reaches the level of balsa and is not very light.

Coosa board

Coosa board is a high density glass fiber reinforced urethane foam sheet from Coosa Composites, available in a variety of densities. It has far greater stiffness and flex strength than balsa or unreinforced foam core materials, making it handy for fabricating free standing structures and bulkheads.

Impact resistance is much better than other cores, making it good for decks and transoms. On the other hand, it is too stiff for curved surfaces; a kerfed balsa or foam is needed for that.

Lamination and bonding are performed using standard epoxy and polyester resin methods.

Construction varies with the panel weight; Bluewater 26, for example, has about 30 to 50 percent of the flexural strength and stiffness of plywood. You can tack rectangular structures together with screws, nails, and staples, speeding the work, but it does not hold screws as well as fiberglass or wood. Lighter grades, such as Nautical 15, require more support.

Even though the panels are much stronger than other cores, conservative design still requires the skins to carry the load for critical structural elements. However, when a stronger grade is used, such as Bluewater 26, nonstructural panels and hatch covers may require only 1-2 layers of 6-ounce fiberglass finish cloth to create a lightweight and extremely durable part. In non-marine applications, if the strength is sufficient, Coosa Board is often used with only a finish. The strength can be considerable in denser grades and greater thicknesses.

Unlike plywood, it will not absorb water and warp. It sands, cuts, and drills accurately and quickly, and the lack of grain makes it practical to carve complex parts. In many ways it is like working with wood, but the result is far more durable once covered with fiberglass.

Areas that are chronically wet such as stiffeners and frames in the bilge are good candidates for Coosa. We also like the high-compression stiffness, making it suitable for mounting hardware or stanchion bases in places where solid laminate is impractical.

Transoms are a great candidate, as is anywhere that plywood is being replaced. We also like it for building interiors, where it is light and stiff.

Conclusions

Coosa has become quite popular with quality powerboat builders, who were looking for something stronger than traditional foam cores and more rot resistant than plywood. We’re not throwing away balsa and low density foam. There are places where these make sense. But we definitely see Coosa board as a superior building material where a stiff, tough, water resistant core is needed. We like it where fasteners must pass through, where impact is a concern, and for small, complex parts.

Related post: Tough, Versatile Coosa Board Suited for Various Projects

I wish I could purchase a sheet of marine grade plywood for less than $32! I think the plywood price should be increased at least two maybe three fold. Still it’s less expensive but with poorer attributes than the alternatives.