What jobs can push down on your ‘to-do’ list for later, and will there come a time when you really regret doing that? Sometimes the answer to that question is obvious. If the engine won’t start or the main halyard fell in a heap at your feet when you tried to hoist it, you aren’t going sailing until you’ve fixed it! What I want to talk about here is not the obvious but rather the hidden problems. Especially if you are relatively new to maintaining a boat, but even for the more experienced skippers, some jobs are not at all obvious. There are jobs you may not even be aware of, but they can lead to very expensive or dangerous situations if left undone. These are the hidden boat killers.

It doesn’t matter if you sail a 16-ft. dingy or a 50-ft., 8-berth cat, they all share similar systems and materials. Regardless of the boat, it will have a steering system, rigging, probably an electrical system and a bilge that can fill with water. It will also be made of a relatively small number of different materials—wood, resin, stainless steel, etc. So, I am going to look at these materials and systems to see what can destroy them without being obvious to the skipper or crew. I am also going to look at the sort of failures in three categories.

Critical – Things that can disable or sink your boat without warning and put lives at risk.

Catastrophic – Serious problems that are really going to spoil your day but not have you calling “Mayday.”

Insidious – Things that creep up without being spotted, but when they eventually are spotted you find they are way more expensive and/or need lots of time and skill to fix.

In general, we’re going to look at things that can lead to the boat being laid up for a month or more of work. This is the classic “stitch in time” but you need to know where the stitch has to go!

WHAT IS STAINLESS STEEL’S DARK SIDE?

Whether your hull is made from resin and glass, wood, steel or aluminum, if it is less than about 50 years old, most of the metalwork will be stainless steel. Those fittings hold the mast up, control the sails and work the steering. If they fail, the result will be critical or catastrophic. But why might they fail? For starters, stainless steel has a dark side, literally. All of those things fitted to your boat have at least one side that is hidden. Chain plates are up against the hull or a bulkhead, all the deck fittings are, well, fastened down to the deck. Even the rigging has a dark side. There are plates fastened to the mast, and any rigging wire has a terminal on the end. Why does this matter?

The dark side of stainless is that the nice shiny finish that you see, which seems almost indestructible is in fact a very, very thin layer that has reacted to the oxygen in the air to form an almost invulnerable skin. Even more magically, if you scratch it, that skin immediately reforms! Wonderful, but this only happens when it is exposed to the air (specifically the oxygen in the air). If there is no air, there is no protective skin and stainless will rust like any other steel. When stainless steel is in the dark and damp—or even worse the warm, dark, and damp—it stops being stainless and becomes common rusting steel! Worse, this only happens where you are unlikely to see it. This is often called crevice corrosion.

So where are these dark, damp places? The inside face of any stainless component fastened to something else is one. Even more importantly, look at how is it fastened to the boat: a stainless bolt that goes through a nice dark hole. So, if stainless steel rusts when not exposed to the air, why don’t boats fall apart within 5 years? Well, that is quite simple. When the boat was assembled, the dark side of every fitting was diligently sealed with caulking. Great, so problem solved? Sort of. Caulking is wonderful stuff, if pretty messy to use, but it has its limits. It does not last forever and fittings also get strained or bolts work loose. When this happens, the waterproof bond will fail and let water in. You now have dark and damp conditions in which the stainless steel can start rusting.

This results in three categories of harm–critical, catastrophic, and insidious. Insidious if the failure is at a stanchion base. It can lead to water seeping into the deck core and eventually rotting it out. It is fixable but can cost more than replacing the boat! Catastrophic if it is the chain-plate bolts that rust and fail, leading to the mast falling down. If it is a keel bolt or through hull… who would have guessed that one of the critical components in your boat is the caulking! The remedy is to keep an eye out for any rust streaks or staining around the fitting and urgently remove them, check and re-bed. It is also worth taking off a few different fittings each winter to redo them even if they look fine.

Ideally all fittings should be re-bedded at 5-10 years depending on how the boat is used. An easy way to keep track could be to divide the boat into areas and do one area each winter. This may look something like this:

Year 1, port side deck fittings;

Year 2 starboard side deck fittings;

Year 3, underwater fittings and rudder;

Year 4, mast and rigging;

Year 5, port-lights/windows

WHAT ABOUT THE RIGGING?

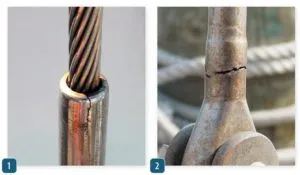

Crevice corrosion is not the only issue with stainless. The next issue focuses on rigging wire. When you took out insurance for your boat one of the questions they probably asked was “How old is the rigging?” If it is more than 10 years old, they probably would exclude anything linked to rig failure in your coverage. But why? What is special about the 10-year time frame? In fact, very little. The insurance company may be just averaging risks. So, what’s the problem with stainless steel wire, other than crevice corrosion in the terminals and fittings?

One property of stainless is that if it is subject to repetitive loading and unloading, exactly the conditions you get when sailing over waves, it can become brittle and eventually crack. You can see this happen if you take a piece of stainless wire and try bending it back and forth. To start, it is stiff, but as you bend it, it gets easier and eventually just snaps. That’s metal fatigue. A similar thing happens, but more slowly, if you stretch it. How fast this happens depends on how much it is loaded. The more load the faster it goes.

closely for micro-cracking that can invite crevice corrosion. A magnifying glass

can sometimes reveal these cracks. Using dye penetrant can also reveal trouble spots. If the age of suspect component is unknown, replacement is often the safe option (see “What’s Hiding in Your Rig,” April 2018).

If you have a wire with a breaking strength of 1,000 kg and load it to 100 kg, that is 10% loading. Do the same with a 10,000 kg wire loaded to 1,000 kg and it is still a 10% load. If you have a cruiser race with lightweight rigging to cut weight aloft, those wires are probably calculated with safe but high loads. At the other end of the scale, I have rigged long-keel traditional sailboats for ocean crossing keeping all rig loads below 5%. The cruiser-racer in this example may need to replace the rigging wire every 5 years. The heavyweight long keeler could be fine after 25 years. The math involved in knowing this is complicated, but it may be worth having a chat with your local rigger/sailmaker who should be able to advise you. If your boat will take it without a notable performance penalty, going up one wire size may make a substantial difference in how long it will last.

CONCLUSION

Where you sail is also important. Crossing oceans means weeks or even months in waves much bigger than coastal sailors normally experience. With each roll, the rigging is loaded and unloaded in hundreds of stress cycles a day. This is why you may hear circumnavigators talking about replacing rigging halfway through a circumnavigation even though it is only 2-3 years old. Incidentally, this is why synthetic rigging is gaining popularity, it does not suffer fatigue from cyclic loading. It may chafe more easily but you can see that and fix it. Corrosion and metal fatigue account for most rig failures but it will still be most likely when you get caught by a wind shift and do a crash jibe or get caught in heavy weather simply because those are the times the rig is under maximum load. The rig came down when you crash jibed because it was already weakened by corrosion and fatigue. I had a mizzen mast fail that was fine for coastal sailing. But after a month of ocean sailing all the tangs snapped at the bend point. The mast also carried the radar unit and the rigging had not been upgraded to allow for the extra loading this created.

Bad days like this are best avoided…and that’s the point.

We’re not finished with our look at boat killers just yet. This week we’ve taken a hard look at the euphemistically dubbed “stainless” steel. We’ve learned its true nature, and we’ve learned about the dangers of complacency. Next week we’re going to look at another maintenance challenge: water intrusion. It will come for you either as a sudden flood or as a slow, insidious seepage. It’s not all bad news. There are ways to get ahead of it…but only if you know what’s coming.

Catastrophic and Critical should be switched around. I would think sinking or a life at risk is catastrophic and worthy of a Mayday call. Critical seems better for an important system, but not life and limb concerning.