Dillinger, the Depression era’s Public Enemy #1 destroyed his fingertips with acid… but was led to slaughter in a Chicago alley in 1934 by “The Lady in Red.”

Boat owners can wear away their fingerprints by hand sanding.

Some hand sanding—cracks, crooks, crevices, corners and curved surfaces—may be unavoidable. The liability: Finger pressure, even when used with sheet paper folded in quarters, usually results in uneven sanding, especially on edges.

Most hand sanding is better done with a fairing board, a rubber block, various foam pads, sticks, tape, roses and pads, all intended to make sanding less onerous… and onerous it will certainly be anyway.

To power sand, there are many approaches using flap wheels and mops; inflatable drums, sleeves and disks on a bench-mounted sanding machine, and air-powered or electric sanding machines.

Unless you choose to go brutal with a belt sander, the best by far on flat surfaces is a random orbit electric sander, sized to be easy to hold for several hours. Buy one too big and it gets extra wearisome.

Random orbit sanders superseded oscillating sanders about 15 years ago. They remove material fast, leave a better surface and make the paper last longer by clogging up less. Use a dust-collector model and the tendency to clog is further mitigated by reducing what is called “swarf.”

The machine chosen by Practical Sailor to test various kinds of sandpaper commonly available to and used by boat owners is a Porter-Cable Model 334, which takes a 5″ PSA (pressure sensitive adhesive) disk with five holes for the dust collector. Although told that the hook-and-loop version is more popular with householders, PS picked the sticky-back version because it is preferred by contractors and because the PSA disks are considerably less costly.

(Here’s a tip: Don’t leave a sticky-back disk on a sander overnight. The adhesive tends to cure and stick to the sander pad when the disk is removed. The unwelcome glue is difficult to get off the pad face.)

The test platform was a $23 piece of 3/8″ plywood, finished one side only (to hold down the cost). A standard size (4′ x 8′), it was cut down to 3′ x 6′ for ease of handling. Sanded even smoother than it came, the plywood was measured off in pencil-marked 6″ x 6″ sections and taped off with 3M’s Fine Line #218 tape in a 1/8″ width. (The 3/4″ version of this pea-green polypropylene tape is popular with boatowners because the paint leaks under the edges less than with cheaper masking tapes with paper bases.)

The Surfaces

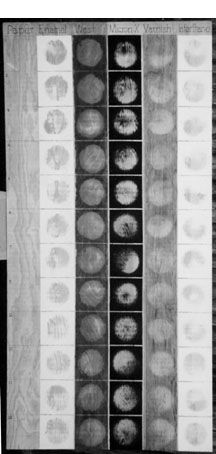

Sandpaper manufacturers often test their abrasives by applying multiple coats of different colors, and sanding until the next color shows through. Practical Sailor elected to apply five different coatings (in whatever number of coats needed to get a typical finish) and simply sand through to bare wood…..a procedure perhaps more typical for a boatowner who is refinishing paint or varnish, or perhaps “wooding” the surface to start afresh.

The five coatings were applied with extreme care, with a special eye to evenness over the entire surface. The West System epoxy is a single, heavy coat. The varnish took three coats to give a shiny finish. Two coats sufficed for the three paints. As shown in columns in the photo on the facing page, they are:

1. Interlux’s Premium Yacht Enamel ($19 per quart), a top-flight one-part, alkyd-based finish.

2. Clear West Epoxy, one heavy coat, applied with a roller.

3. Micron Extra, ($48 per quart), an ablative copolymer anti-fouling bottom paint that was one of the three top paints in Practical Sailor’s most recent bottom paint report in the March 2001 issue.

4. Interlux’s Schooner varnish ($19 per quart), which was one of the three best varnishes in the 20-brand test report in the same March 2001 issue.

5. Interthane Plus ($70 per quart), a two-part polyurethane enamel.

After all the measuring, taping, coating, re-taping and recoating, the finished plywood panel (with 60 sections) was set aside for 10 days—which is a “safe” time to allow paint and varnish to harden.

(Here’s a tip: You generally can tell when paint or varnish is cured by smelling it; it loses its odor. As it ages further, most paint and varnish hardens even more, gets brittle and is more difficult to remove by any means.)

The Sandpapers

In the US, there are lots of little players, but only three big ones in the sandpaper business. They’re so big, they tend to just ignore the many small companies and grind away at each other. They have manufacturing facilities scattered everywhere.

The Big Three are Carborundum, Norton and Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing (3M). Carborundum, commonly called Carbo, and Norton were purchased in the early 1990s by a French conglomerate—St. Gobain. It was a good global-economy buy.

Both Carbo-Norton and 3M have new top-of-the-line products intended to make it half as difficult for you to sand your toerails—and, by doing so, knock the other outfit on its heels.

Added to the Big Three’s products were five other sandpapers found in hardware and woodworkers’ stores.

As a general rule, coarse grit paper has heavier backing and costs more than fine grit paper. As mentioned above, hook-and-loop disks cost more than sticky-backs. Throughout this report and on the chart, the prices will be for 80-grit, 5″, 5-hole, PSA paper.

In all, 12 varieties of sanding disks from seven manufacturers were tested. In all cases, these were not the cheapest sandpaper made by these companies. Here in alphabetical order (by the manufacturers’ names) is a brief description of each variety.

The expert refinishers in the Caribbean, noted for their varnish work, recently have been extolling a sandpaper they call “Big Red.” Carborundum has changed the name of “Big Red” to “Premier Red”; the Caribbean detailers still call it “Big Red.” It’s Carbo’s top paper. Also in the test is Carbo’s workaday Carbo Gold, a less expensive paper.

The Indasa disks shown on the chart were purchased at a tool specialty store, whose clerks touted it as a “good paper at a good price”. The price was 35¢ a disk. Called Rhynalox (the company logo is a rhinoceros), the disks are “D” weight paper and aluminum oxide. The sticky side of the disks have thin plastic backing sheets that are removed with a tab. The packaging indicates that the Rhynalox is made in Portugal and imported by Tru-Mark Products, 16 Herbert St., Newark, NJ 07105.

Great reports were given by Bill Siefert, a Practical Sailor friend, to a Finnish sandpaper named Mirka, whose symbol is a bulldog. Bill even supplied the catalog from which he regularly orders. It’s Woodworker’s Supply (800/645-9292). John Wirth, who owns the company, contacted the US importer of the Mirka paper (330/963-6421), who sent along several kinds of 80-grit paper.

Mirka’s Royal paper, which Woodworker’s Supply sells as “Premium Gold,” is a latex-backed paper. It costs about 25¢ each in rolls of 100. (The hook-and-loop version is about 35¢ a disk in lots of 50.)

The other is Royal Coarse, an “F” weight paper/gauze disk with a tougher edge than other papers. The thick edge better withstands wear on the rim. The expensive Royal Coarse is meant for serious material removal.

Norton is represented in the test by two kinds of paper. Champagne Magnum, aluminum oxide on a paper backing, is a tough sandpaper that’s been on the market for several years.

The other Norton, called “Blue” or #A975, is so new that distributors and Norton customer service numbers reported that little information is available other than that it’s listed as “experimental.” It appears to be paper-backed with a heavy coating on the working face, whose grits are a blend of ceramics and heat-treated aluminum oxide. No prices were available.

The single example of Sears Roebuck & Co. disks had an advantage in this test. Although all other disks are 80-grit, Sears had only “Coarse,” or 60-grit. Other Sears disks came in medium, fine and extra fine. The package indicated that the Sears disks, which are aluminum oxide on a paper back, were made in Canada. Even considering that they come in four-packs, which one would expect to be more costly than 100 lots, they cost $2.49 a pack or 62¢ a disk. That’s an outlandish price!

The Sungold disks, purchased at a Woodworker’s Warehouse store, were stamped “Made in the U.S.A.,” but the maker is not shown. The Sungold is silicon carbide on paper with a peel-away backing (like the Rynalox from Portugal)). A package of 50 cost $14.95—or 30¢ a disk.

The three 3M sandpapers in this test are the very new, film-backed Imperial (which is purple-colored), and two versions of 3M’s extremely successful “Gold,” which was 3M’s top paper until the introduction of Imperial. One Gold is film-backed (#255L). The other Gold is “C” weight paper-backed (#236).

How The Test Was Done

The testing was done with 80-grit disks (except for the 60-grit Sears Roebuck disks). Eighty-grit is, in the industry, called a “cross-over grit.” meaning that it’s on the line between stock removal and surface finishing.

(Here’s a tip: Because a random orbit sander leaves a smoother surface than other sanders, 80-grit paper can be used for a fairly good surface that, with an in-line or orbital sander, might require 120-grit. However, for a really fine finish, you need after the 80-grit a pass with 120-grit. The rule in sanding is never to go up more than one grade at a time—for instance, 80 to 120 or 120 to 150 is okay, but it’s wasteful to go 80 to 180 or 120 to 220.)

Each variety of paper was tested on the five coated surfaces. A new disk was used on every section of the test panel.

Using moderate hand pressure on the Porter-Cable sander, Practical Sailor timed how long it took each paper to cut through the coated surfaces to bare wood. The disk then was removed from the sanding machine, marked and later examined for clogging.

The clogging is important. The five surfaces used in this test are so soft, compared with the grit used on these sandpapers, that the sandpaper doesn’t wear down very much. Most disks are discarded because heat build-up encourages clogging. The clogging supposedly can be removed by holding a block of gum rubber on the surface, but even sandpaper manufacturers concede that these giant “erasers” don’t work very well if the material is really cooked.

Using a dustless model sander and a strong vacuum to collect the dust meant that a minimum amount of debris was left to clog up the surface of the papers. It gave each kind of paper its very best opportunity to look good in this test.

The Bottom Line

The test results are displayed on the accompanying chart (click here).

One conclusion is inescapable. The best paper is far better than the cheap paper… and really cheap paper (the kind you might run into in a “big box” store) wasn’t even tested! The premium sandpapers more than make up the price differential by working better and lasting far longer. Considering all the human effort and time can be invested, why choose cheap paper?

None of these sandpaper disks worked well on the bottom paint; they all load up too much. And all but the Sears paper worked on two-part paint, but expect to spend some time if you’re removing such tough paint.

The test demonstrated how two or three well-run companies, competing vigorously in price and quality, do nothing but make it better for consumers. And if they fail to do so, some little domestic upstart or a foreign competitor will cut them to ribbons with a new sandpaper made of castellated, crystallized, stone-ground oatmeal. It’ll be named something like “Battle Royal”.

The final cut? There is not much to choose between the top sandpapers of the Big Three. Sharing honors for Best-in-the-Test were Carborundum’s Premier Red, Norton’s new Blue (A975) and 3M’s very new, purple-colored Imperial.

If forced to pick a winner, it would be 3M’s Imperial. It performed beautifully on all five test surfaces, but is burdened with a mean price.

Throwing cost into the equation means that win, place and show go to Carborundum’s Premier Red, Norton’s Blue and 3M’s Imperial.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Sandpaper Facts to Ponder While Applying Elbow Grease.”

Click here to view “Alternative to Chemicals.”

Contacts- Carborundum & Norton, 800/268-2262 or 800/377-0331. Indasa, retail stores, www.indasausa.com. Mirka, Woodworker’s Supply, 1108 North Glenn, Casper, WY 82601-16988, 800/645-9292, www.beta.woodworker.com. Sears, any store. Sungold, retail stores. 3M, 3M Marine Center, Bldg. 250-1-02, St. Paul, MN 55144, 651/737-4171, www.3m.com.