Fiberglass, also known as glass-reinforced plastic (GRP), has been an integral material in modern engineering and design, especially within the marine industry. Its lightweight, durable, corrosion, and marine organism-resistant properties have made it a favored choice for boatbuilders since the mid-20th century. But what of its origins?

In my own search to understand how fiberglass swept the world by storm, I set out to trace the material’s historical development, technical composition, and ‘revolutionizing’ impact on the marine industry, particularly in recreational and competitive sailing.

As far back as 1600 BCE, ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians were experimenting with pulling glass into fibers for decorative purposes, weaving them into garments and ornamental items. Yet, while these early uses of glass fibers were limited to decorative applications, it wasn’t until the 20th century that fiberglass as we know it—composite glass fibers embedded in resin—was developed for practical, large-scale use. The modern revolution of fiberglass has since had a profound influence on industries, including boatbuilding.

Yet, this story must also confront the true cost of GRP: the environmental impact of its production, the challenges of its disposal, and the lack of foresight regarding its end-of-life implications. We now face difficult questions about its legacy and the urgent need for sustainable alternatives to mitigate the growing problem of fiberglass waste.

AN ACCIDENTAL INVENTION

The discovery of fiberglass in the 1930s was the result of an unintentional breakthrough during an experiment conducted by Dale Kleist at the Owens-Illinois Glass Company. Kleist was attempting to create an airtight, vacuum-tight seal between two glass blocks using high-pressure air and heat. The goal was to fuse the blocks together, but during the process, a stream of molten glass was unexpectedly blown into fine fibers. This accidental discovery revealed the potential of glass fibers, highlighting their strength and versatility (Slayter, 1938).

Recognizing the importance of this unexpected innovation, further research was conducted to explore its industrial applications. However, it was the work of Russell Games Slayter at Owens-Corning that led to the development of fiberglass as we know it today. In 1938, Slayter filed a patent for the production of glass fibers reinforced with plastic resin, creating a material that was strong, lightweight and durable. Initially, fiberglass was used primarily as an insulation material due to its thermal resistance and non-conductive properties, but its potential for broader applications quickly became evident (Slayter, 1938).

WARTIME DEMAND AND THE GROWTH OF FIBERGLASS

While fiberglass’s initial applications were in the insulation of electrical and mechanical components, World War II played a critical role in advancing its use. The U.S. military recognized the material’s value, as it was lighter than metal, resistant to corrosion, and non-conductive, making it ideal for use in radomes, the protective domes for radar systems. Fiberglass was also used in aircraft components, electrical insulation for ships, and even for structural elements in certain military vehicles (Huntington, 2001).

In Nazi Germany, similar wartime material shortages led to an exploration of synthetic materials, including early forms of composites like GRP. The regime’s focus on Bakelite, synthetic rubber, and other plastics was driven by blockades and limited access to raw materials such as steel and aluminum. While Germany was not at the forefront of fiberglass development, its wartime emphasis on alternatives to traditional materials hinted at the growing potential for composites like GRP in the post-war world (Pech, 2014).

POST-WAR BOOM AND FIBERGLASS’ ROLE IN THE MARINE INDUSTRY

The post-war period was a pivotal moment in the development and mass production of fiberglass, particularly as industries sought new materials that could be mass-produced efficiently and at scale. The marine industry was no exception. The ability to build lightweight, corrosion-resistant, and durable boats marked a revolutionary shift from traditional wooden boat construction, which had dominated for centuries.

Ray Greene, a boatbuilder from Ohio, is credited with constructing the first fiberglass boat hull in 1942. Greene’s pioneering work was largely experimental at the time, as fiberglass was still a novel material, and its full potential had yet to be realized. However, this laid the foundation for broader adoption in boatbuilding.

By the late 1950s, fiberglass had overtaken traditional materials like wood, with companies like Chris-Craft, Pearson Yachts, and Bertram adopting fiberglass for mass production. Former Practical Sailor Editor Dan Spurr, in his book Heart of Glass, highlights how the post-war recreational boatbuilding boom was fueled by the benefits of fiberglass, including ease of production, cost reduction, and performance improvements. The Pearson Triton, introduced in the mid-1950s, became one of the first mass-produced fiberglass sailboats, signaling a cultural and industrial shift. The Bertram 31 sportfishing boat further cemented fiberglass’s place, showing its strength and durability in offshore conditions.

Importantly, the cultural shift was not just about technological progress. As boats became more accessible, boating itself became a middle-class pursuit, a leisure activity enhanced by fiberglass’s lower maintenance needs and longer lifespan. Traditionalists initially mocked fiberglass boats as “plastic fantastics” (still used today) or even “frozen snot” (a term attributed to wooden boatbuilder El Francis Herreshoff), but owners quickly appreciated the lower upkeep and longer lifespans.

THE SCIENCE BEHIND FIBERGLASS IN BOATBUILDING

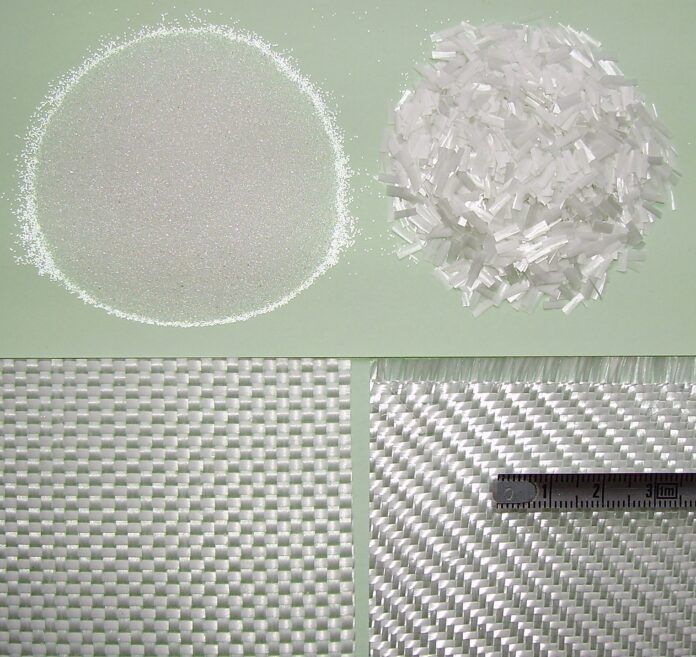

The success of fiberglass in the marine industry could be attributed to its composite structure. Fiberglass is made by combining fine glass fibers with a resin matrix (usually polyester, vinyl ester, or epoxy resin). This composite system works by distributing loads across the resin, while the glass fibers provide tensile strength. The combination results in a material that can withstand the dynamic stresses encountered in marine environments, including wave impacts, wind forces, and the wear from saltwater exposure.

Several types of fiberglass have been developed:

- E-Glass: The most commonly used fiberglass in boatbuilding. It is strong, inexpensive, and resistant to environmental degradation, making it ideal for most recreational sailboats.

- S-Glass: Provides superior strength compared to E-glass and is used in high-performance racing sailboats and specialized marine applications. Its higher tensile strength allows for the construction of lighter, faster vessels.

- C-Glass: Known for its chemical resistance, C-Glass is less commonly used in recreational boatbuilding but is valuable for marine applications where exposure to corrosive chemicals, such as fuel or industrial waste, is a concern (Tucker, 2012).

MANUFACTURING TECHNIQUES

The most common technique for building fiberglass boats is hand lay-up, a process where layers of glass fabric are placed in a mold and then saturated with resin. This process is labor-intensive but allows for great flexibility in terms of hull shape and thickness. Advances in the 1960s and 1970s introduced more automated methods, such as vacuum bagging and resin infusion, which provide better control over fiber-to-resin ratios, resulting in lighter, stronger boats.

Vacuum infusion is particularly important in modern boatbuilding. This technique involves placing dry layers of fiberglass into the mold and then using a vacuum to draw resin into the mold. This method minimizes the amount of resin required while ensuring that the fiberglass is fully saturated, leading to a stronger, lighter structure. It is now widely used in the production of high-performance racing sailboats and large yachts.

THE TECHNICAL CHALLENGES OF FIBERGLASS

Despite the early promise that fiberglass boats would last forever with minimal maintenance, reality quickly proved otherwise. In the rush to mass-produce GRP boats in the 1960s and 1970s, many manufacturers overlooked the long-term durability issues that would emerge with time. While fiberglass’s resistance to rot and corrosion made it an attractive alternative to wood and metal, several technical challenges began to surface, especially as boats aged. These problems, exacerbated by the use of lower-cost resins in many mass-produced boats, have since become significant concerns for boat owners.

Boat pox. One of the most common issues plaguing fiberglass boats is osmosis, often referred to as “boat pox.” Osmosis occurs when water penetrates the gel coat and reacts with unreacted chemicals in the laminate. This results in blistering as the trapped water forms pockets between layers of fiberglass, leading to structural weakening. While early manufacturers believed that the gel coat would provide a near-impermeable barrier against moisture, it became evident that even small imperfections could allow water to seep through, particularly in hulls that were exposed to water for extended periods. Over time, these blisters could compromise the integrity of the boat, requiring costly repairs and maintenance.

UV degradation. Another significant challenge is UV degradation. Although fiberglass itself is resistant to UV rays, the resins used in the construction of the boats are not. Prolonged exposure to sunlight causes the resin to break down, leading to discoloration, weakening, and surface chalking. This degradation not only affects the aesthetic appearance of the boat but also reduces the strength of the fiberglass composite. Without regular maintenance and protective coatings, UV damage can drastically shorten the lifespan of a fiberglass boat.

articles on products and remedies to repair blisters.

Mass-produced boats, particularly those built with cheaper polyester resins, are more prone to these issues. Polyester resins, while affordable and widely used, are more brittle and less durable compared to higher-quality epoxy resins. Over time, the use of cheaper resins has proven to accelerate problems like osmosis and UV degradation. In contrast, epoxy resins offer superior water resistance and UV stability but remain cost-prohibitive for widespread use in recreational boatbuilding.

These technical problems reveal the gap between the early promise of “invincible” fiberglass boats and the reality of long-term ownership. As fiberglass boats age, the need for significant maintenance and repair becomes evident, challenging the material’s reputation as low-maintenance and enduring. For boat owners, the true cost of fiberglass often emerges years after purchase, as they grapple with the financial and environmental consequences of repairs, refinishing, and—eventually—disposal.

THE TRUE COST OF FIBERGLASS

While fiberglass revolutionized boatbuilding with its lightweight, durable, and corrosion-resistant properties, its environmental and social costs were not considered during its post-war adoption. The material’s lack of biodegradability means that abandoned fiberglass boats persist indefinitely, contributing to environmental pollution. As fiberglass boats degrade, they release harmful microplastics into marine environments, exacerbating the growing issue of plastic pollution in oceans (Geraghty et al., 2024). These microplastics pose significant threats to marine ecosystems, where filter feeders like oysters and mussels ingest fiberglass particles, causing potential disruptions to marine food chains (Ciocan et al., 2024).

A 2019 report for the International Maritime Organization suggested there were around six million fiberglass boats in the European Union alone. Of these, approximately more than 100,000 GRP boats in the EU reach the end of their useful life, with only 2,000 recycled, while 6,000 to 9,000 are abandoned (accounted for). This leaves approx. 90 to 100,000 boats per year, completely unaccounted for, likely abandoned. This lack of disposal infrastructure exacerbates the environmental crisis, as harmful chemicals leach from these vessels into sensitive marine ecosystems, impacting water quality, marine life, and coastal habitats. Additionally, abandoned or derelict vessels create navigational hazards, and they often end up becoming long-term environmental burdens due to the absence of comprehensive recycling solutions.

The production of fiberglass also involves the release of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), especially during the manufacturing of polyester and vinyl ester resins, which are derived from petrochemicals. Epoxy resins, while emitting fewer VOCs, are still costly, petro-chemical derived, and remain impractical for widespread at scale in recreational boatbuilding. These environmental challenges are compounded by the absence of a comprehensive recycling plan for fiberglass boats. Without more stringent policies and better disposal infrastructure, fiberglass production and end-of-life management will continue to harm marine ecosystems and human health.

IMPACT ON SMALL ISLAND DEVELOPING STATES (SIDS)

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) have been particularly affected by the proliferation of fiberglass boats. The popularity of fiberglass boats in tropical climates led to widespread adoption in these regions during the 1970s and 1980s. However, the lack of infrastructure to manage end-of-life fiberglass boats means that many islands now face significant environmental issues as derelict vessels accumulate along shorelines. Due to the durability and longevity of fiberglass, abandoned vessels in SIDS often remain intact for decades, creating long-term environmental hazards. This not only threatens sensitive ecosystems like coral reefs and seagrass beds but also impacts local economies that depend on tourism and fishing (Mohee et al., 2015). Given the limited waste management infrastructure in these regions, abandoned fiberglass boats pose a particularly acute challenge, and more sustainable disposal solutions are urgently needed.

FIBERGLASS AND THE FUTURE OF MARINE CONSTRUCTION

the breaking strength of the composite structure.

As the marine industry looks to the future, new materials are beginning to challenge fiberglass’s dominance. Carbon fiber composites offer greater strength and weight savings but come at a high cost and are energy-intensive to produce, raising their own environmental concerns. While carbon fiber is increasingly popular in high-performance racing yachts due to its superior strength-to-weight ratio, its production process remains highly energy-intensive, and like fiberglass, recycling carbon fiber is challenging. The environmental footprint of carbon fiber, despite its performance benefits, may in some cases be worse than that of fiberglass. Its higher cost also restricts its use to niche markets, including luxury and racing yachts, where performance outweighs financial and environmental costs.

SUSTAINABLE ALTERNATIVES

Meanwhile, the marine industry is also exploring more sustainable alternatives. Fiber composites made from materials like flax, hemp, and basalt, are gaining traction as a more environmentally friendly option. These ‘bio-composites’ offer lower carbon footprints and are more biodegradable than traditional fiberglass, making them an attractive option for boatbuilders focused on sustainability. Although these materials do not yet match the strength and durability of fiberglass, research and innovation in this field are rapidly advancing. The durability and long-term viability of bio-composites remain under investigation, but they offer a promising step toward reducing the environmental footprint of the marine industry.

Another area of focus is bio-based resins, which are derived from renewable resources such as plant oils. Bio-resins reduce reliance on petrochemicals and help lower the environmental impact of fiberglass construction. Although bio-resins are not yet as widely adopted in marine construction, continued advances in this technology may make them a viable alternative in the coming years (Turner & Rees, 2016). As the technology becomes more affordable and efficient, bio-resins have the potential to significantly reduce the environmental impact of boat production and extend the lifecycle of sustainable materials.

Hazardous waste? The increasing environmental impact of GRP waste has led to growing calls for its classification as hazardous material. If fiberglass were classified as hazardous waste, it would subject the material to stricter regulations, mandating safer production, disposal, and recycling practices. The importance of reclassifying fiberglass as hazardous waste lies not only in curbing its production but also in driving innovation in more sustainable and regenerative materials. This shift in classification could drive much-needed investment in sustainable disposal technologies, encouraging the marine industry to explore regenerative alternatives (Geraghty et al., 2024).

Organizations such as OSPAR, which works to protect the marine environment, have advocated for stronger policies to address the environmental hazards posed by GRP. By recognizing fiberglass as a significant pollutant, OSPAR and other organisations could catalyze industry-wide changes, promoting the development of more sustainable materials and better end-of-life management for fiberglass boats. Additionally, this classification could spur governments to enforce Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programs, holding manufacturers accountable for the entire lifecycle of their products, from production to disposal.

Increasing costs. However, it can be argued that classifying GRP as hazardous waste without robust and cost effective ways to dispose of and process that waste may be the wrong approach. Robert Dunford, Deputy Harbour Master at the Langstone Harbour Board, explained they have spent almost three percent of their budget over recent years dealing with end-of-life vessels, not including staff time. His concern is that classifying fiberglass as a hazardous waste will likely triple these expenses. “As in most cases, it is not a statutory requirement to deal with wrecks that don’t pose a navigational risk, pushing up the cost will mean that wrecks simply will be left on the beach,” Dunford commented.

WHERE TO FROM HERE?

Fiberglass revolutionized the marine industry by making boatbuilding more efficient and accessible, offering durability, strength, and low maintenance that fueled the industry’s rapid growth in the 20th century. However, as fiberglass boats age, technical problems such as osmosis, UV degradation, and the accelerated wear of boats made with lower-cost resins have emerged, undermining the early promise of “invincible” hulls. These issues have not only increased the long-term costs for boat owners but have also added to the environmental burden as boats require more frequent maintenance and repairs.

As fiberglass boats reach the end of their life cycles, the environmental toll becomes increasingly apparent. Exponential growth often comes at a significant ecological and human cost, and the ocean—the ecosystem upon which both sailors and humanity depend—is now bearing the brunt of this material’s widespread use.

While emerging materials such as bio-composites, advancements in recycling technologies, and bio-resins offer hope for a more sustainable future, the marine industry must commit to these innovations if it is to mitigate the long-term impact of fiberglass. The future of boatbuilding will rely on striking a balance between performance, affordability, and environmental responsibility. Greater innovation and investment in regenerative materials are crucial to protecting our oceans and ensuring the sustainability of the marine industry for generations to come.

CONCLUSION

For those contemplating the purchase of a new GRP boat, it is crucial to weigh the long-term environmental costs against the immediate benefits. While fiberglass provides durability and ease of maintenance, its lasting environmental impact, compounded by technical challenges, cannot be overlooked. With millions of fiberglass boats already contributing to pollution, now is the time to think critically about more sustainable alternatives. By choosing more responsible materials and supporting efforts to improve disposal and recycling processes, boaters can help reduce the ecological footprint of their lifestyle. After all, preserving the health of our oceans is just as essential to our future as the enjoyment we seek from being on the water.

REFERENCES

Ciocan, C., Annels, C., Fitzpatrick, M., Couceiro, F., Steyl, I., & Bray, S. (2024). Glass reinforced plastic (GRP) boats and the impact on coastal environments. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 472, 134619.

Geraghty, P., Fannon, J., & Clarke, R. (2024). Sustainability challenges in marine composites: Addressing fiberglass boat end-of-life solutions. Journal of Marine Sustainability, 15(3), 312-329.

Huntington, J. (2001). Fiberglass boats: Construction, repair, and maintenance. McGraw-Hill.

Mohee, R., Mauthoor, S., Bundhoo, Z. M. A., Somaroo, G., Soobhany, N., & Gunasee, S. (2015). Current status of solid waste management in small island developing states: A review. Waste Management, 43, 539-549.

Pech, W. (2014). Technological development in Germany during World War II. Journal of Historical Research, 12(4), 345-368.

Slayter, R. G. (1938). U.S. Patent No. 2,123,992. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Spurr, D. (1999). Heart of glass: Fiberglass boats and the men who made them. International Marine/Ragged Mountain Press.

Turner, M., & Rees, G. (2016). Recycling of composite materials: Opportunities, challenges, and environmental impact. Journal of Materials Science, 51(12), 5453-5467.

Good article!

Has the USEPA opened any recent discussion relating to regulation of disposal of used fiberglass vessels and other GRP structures as hazardous waste or as a special waste? I see one study in 1991, but it primarily addressed production wastes, such as uncured resins and solvents. My gut feeling is that this is so far down the priority list that a rule making effort could never find funding, at least at the federal level.

It seems to me the hazards would be mostly airborne particulate of the sort OSHA can regulate, relating to the demolition process, but not from residing in the ground. If anything was going to leach, it most has over time, and the toxicity of the leachates that occur will fall in the usual range of landfill leachate, which itself is not a basket of fruit. I’ve been involved in the engineering and operation of treatment systems.

Interesting.