Owning a boat is an exercise in perspective. A gale can make a sailboat feel like a canoe, while the prospect of bottom paint removal turns the same hull into something akin to a cruise ship. Old bottom paint always seems to have a split personality, with some portions of the antifouling coating flaking off the hull like a snake shedding its skin and the remainder stuck like glue. The poorly adhered portions of the hull coating encourage us to go ahead with our ambitious plans to strip the bottom, even though the well-adhered regions will slow the removal process to a snails pace. Thats why its important to be a realist when deciding whether or not its time to strip the bottom and deciding who is going to do the work.

The optimist picks up a scraper and heads toward the flaking areas of the hull. With just a few gratifying pushes or pulls, paint debris rains from the hull, and it seems like the job can be completed in hours, not days. The more pessimistic among us scrape away at the well-adhered paint, and discover that the walk in the park is more like a climb up the face of El Capitan. Its the realist that adds up the surface area of paint that is ready to let go in a hurry and compares it with the area that remains well adhered to the hull-only then deciding whether or not to roll up his or her sleeves, open the wallet, or slap on another coat of paint and go sailing.

In the March 2009 issue, PS Technical Editor Ralph Naranjo tackled the challenge of removing bottom paint and a failing epoxy barrier coat on the bottom of his classic Ericson 41. The process was an extreme test of chemical strippers and sharp chisels, scrapers, and patience. (See Practical Flashback, on page 19.) But during each day of this DIY mountain climb, he dreamt about alternatives to the sand and stripper approach to paint removal and wondered whether or not a bottom-blaster could have cleaned the slate in hours rather than weeks. Since then, hes been on the lookout for new trends in paint removal, and this update compares the Franmar Soy Strip chemical approach, our favorite in the earlier rounds of paint removal (March 2009, April 2008, and November 2006 issues), with the latest trends in sodablasting.

Background

Before picking a process for addressing an ailing hull bottom, you need to define your goals and recognize that theres good reason to be as minimally invasive as possible. If all thats wrong with the underbody is flaking bottom paint, and theres no sign of blistering, gelcoat crazing or cracking, then the last thing you want to do is damage the gelcoat. In essence, your goal is to remove the antifouling paint and leave intact the gelcoat-and if one exists, the barrier coat. Doing so requires finesse, whether it involves a sanding process, dry/chemical scraping, or sodablasting.

The most vigorous approach to bottom woes is known as the peel process-major surgery that involves a mechanical cutter thats used when deep blistering and delamination problems arise. This approach incorporates a power plane-like device on an articulating arm that cuts through paint, gelcoat, and even the top layer(s) of fiberglass-reinforced plastic (FRP) laminate. Left in its wake is raw FRP laminate with blisters open and craters exposed. After flushing, cleaning, and spot repairing damaged laminate, a full-scale relamination of the outer FRP skin takes place, followed by fairing, barrier coating, and bottom painting. Its a major, high-cost job that requires intrusive FRP surgery. Fortunately, those who are looking to remove only the old bottom paint can take just the opposite tack and target the preservation, rather than the removal, of as much substrate as possible.

The slow and arduous task of hand-scraping does just that. Its destructive power is minimal, and the user learns a few tricks of the trade-such as rounding the edges of every scraper and letting the chemical stripper sit just long enough to soften the paint but not attack the gelcoat. Power sanding can also be a viable alternative for those with the right equipment and tool-handling dexterity. In order to speed up the process, 36- or even 24-grit abrasive is used on thick paint buildup by those wielding a powerful rotary/orbital sander. Those lacking the deft touch of a pro can easily put polyester divots in the gelcoat. Its also a dirty job that many yards will not allow the DIY owner to engage in. Vacuum-assisted sanders, such as those made by Fein, are helpful in containing the inherent sanding dust. Also available are a wide range of chemical strippers covered in the previous PS issues listed above. For all of these reasons, many prefer to hire the boatyard staff or a subcontractor to tackle the bottom paint removal.

Sodablasting 101

Sandblasting has been around for decades and is part of the infernal thrum of every commercial shipyard. At the heart of the process is a high-volume, high-pressure air supply that can lift aggregate from a hopper and propel it through a hose to a nozzle that directs the flow just like water through a garden hose. Instead of a splashing spray, the resulting impact can scour rust from steel, or rip gelcoat and FRP skin right off a hull. In fact, sandblasting has become less popular as a prep method in major blister repairs because of how much surface destruction occurs during the cure. Sodablasting is a very different story, and the unique softness of the calcium carbonate powder yields an abrasive capacity thats just enough to strip bottom paint but will leave the gelcoat intact.

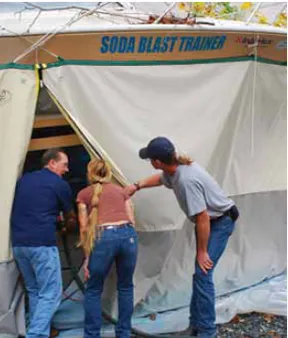

Stacey Stone, the owner of Chesapeake Soda Clean, introduced us to the technology and techniques behind the process. In addition to contracting jobs in the mid-Atlantic region, he trains technicians and sells blasting equipment. One of his most valuable contributions has been his efforts to come up with a process that controls the invasive cloud of bottom paint debris and calcium residue that originally caused yacht yards to shy away from the process. These environmental and cosmetic concerns led him to team up with a boat-bottom tenting manufacturer, Bad Dust Containment Systems, which is run by Brian De Wolf and Roxanne Winslow in East Haddam, Conn. They make modular nylon, reinforced, zip-together tent segments that can be quickly set up around the hull of a boat and sealed with a gasket of tape. The rugged cocoon is then inflated into shape with a high-volume, low-pressure blower. These expandable, reusable containment systems save on one-time plastic sheeting costs and waste.

When it comes to the sandblasting process, Daniel Bernoulli, the Dutch-Swiss mathematician most famous for his studies in fluid dynamics, deserves lots of credit. Negative pressure induced by velocity changes in air flow lifts the powdered soda from the hopper, and it is accelerated by the high-pressure air flow on its way to impacting the surface. At the heart of the blasting kit is a diesel-powered air compressor that does the same job as its diminutive nephew on sale at Sears. But the result is like comparing a faucet to a fire hydrant. Blasting sand, soda, or any other aggregate is all about lots of air and a significant amount of pressure.

Bernoulli understood how the change in shape or contour over a specific surface can impact pressure. A partial vacuum can be created by forcing air through a contoured shape, and when linked to a hopper, the suction will allow media to be siphoned directly into the airflow. A media volume-control valve is used to vary the amount of soda allowed to be lifted into the air flow. Theres even an air-conditioned cooling loop that strips moisture from the compressed air and keeps water from impeding the abrasive process.

The nozzle on the end of the hose has a smaller opening diameter than the hose itself and further increases the air pressure, which also increases the tip velocity of the media expelled from the nozzle. The operator of the system sweeps the tip back and forth over the surface, operating the unit as if it were giant eraser able to peel away even well-adhered sprayed-on coatings. Each sweep of the tip causes accumulated bottom paint to fly from the surface. The resulting cloud of soda dust and paint residue will spread everywhere if not kept isolated by a significant tenting effort. Needless to say, the operator is swathed in a suit, gloves, and boots and connected to a remote air supply fed to a respirator, helmet, or full face mask.

A Tale Of Two Pearsons

In order to have a baseline for evaluating the sodablasting process, its cost and outcome, we compared two bottom-paint stripping approaches carried out on two similar-era Pearsons. The first Pearson began as a do-it-yourselfer endeavor that ran smack into reality-too little time and too much paint adhesion. The owner switched tacks, and the yard pros took over, using a combination strip-and-sand approach to deliver a ready-to-paint bottom. The second Pearson, a P36, sported a decades worth of well-adhered buildup that needed to be removed from the hull. The owner contracted with a freelance mobile sodablasting crew, Chesapeake Blasting Services.

The blasting crew arrived on the scheduled date at 6:30 a.m., hoping to be set up and ready to go before the full heat of a Chesapeake summer day took hold. In a matter of about two hours, they had repositioned jackstands over a plastic drop cloth, and taped and clamped an encapsulating plastic skirt around the perimeter from just above the waterline to mate with the drop cloth itself. By 8:30 a.m., the two sodablasters were ready to fire up the compressor and get started.

In both cases, the final outcome was a high-quality clean surface, undamaged by the paint removal process, with only a few minor repairs to make before barrier coating and bottom painting could be carried out. The big difference was that the Chesapeake Blasting Services crew had the job completed by 3:30 p.m. the same day, all signs of the debris and dust (from using 3 50-pound bags of media) had been contained and carefully removed from the site. The pros that used the more conventional chemical-stripper and sanding approach, spent three times as long to achieve a similar result, and the average costs for such work among the yards we caucused ranged from $1,700 to $2,800-all more than the $1,600 sodablasting charge.

Conclusion

Sodablasting is clearly a recommended means of bottom paint removal. Its cost effective, often the least expensive of the options that involve a yard or outside contractor. Its lower-impact status leaves vital gelcoat undamaged but removes 99 percent of the paint. Many boatyards are moving toward relationships with independent blasting subcontractors, and time will tell whether or not the process grows into the preferred approach for bottom paint removal. In the mid-Atlantic, its a growth industry that leaves customers and boatyards happy with the results.

The Pearson 36 owner received an estimate of $1,400 to $1,600 for the work, and according to Chesapeake Blasting Services owner Mike Morgan, the vessel represented a middle-of-the-road challenge, as far as the difficulty of the job.

Just as important as what sodablasting can do, is what it will not do, and when it comes to removing epoxy barrier coats and linear-polyurethane top coats, these materials are too hard, and their adhesive quality makes them immune to sodablasting. In such cases, more abrasive media is needed. Morgan and Stone like what glass-bead blasting can do with these tougher coatings. There are a number of practitioners using this media in conjunction with air as well as water jet blasting, and in a future report, we will take a close look at more aggressive substrate removal options.

It’s easy to underestimate the amount of actual work involved in scraping and sanding old paint.

An easy way to compute the do-it-yourself labor commitment involved is by timing how long it takes to scrape clean two 1-square-foot patches. The first is in the center of the least well-adhered paint; the second is in the midst of an intact portion of the bottom. Dry scrape each section with a thin-bladed putty knife and a sharp drag-type scraper, noting the time it takes to remove about 90 percent of the coating.

Next, estimate the percentage for the bottom that should be dubbed easy to scrape paint versus areas where the antifouling is stuck like glue. Finally, you need to roughly calculate the square footage of wetted surface area (WSA) that comprises the underbody. This is by no means an ordeal that requires advanced geometry. It’s a rudimentary calculation that requires only three bits of information (waterline length [Lwl], maximum waterline beam [Bwl] and draft [T]). The user-friendly formula (WSA = Lwl x (Bwl + T) applies to most heavy displacement cruising hulls. Multiply by 0.75 for medium-displacement vessels and 0.5 for light-displacement boats. This oversimplification of wetted surface calculation would provoke a scolding from David W. Taylor, William Froude, and other dons of naval architecture, but for a paint removal estimate, it works just fine.

Finally, take the results of the calculation and divvy it up according to the proportion of easy versus difficult regions of paint removal. For example, if only 15 percent of the bottom is cracked and peeling, and the removal time per square foot in this region is 30 seconds—as compared to four minutes per square foot in the well-adhered section—the ratio is by no means encouraging. Applying the ratio to the wetted surface calculation drives home the level of paint scraping required.

Let’s assume that the vessel has a 30-foot waterline, 6-foot draft, a waterline beam of 10 feet, and is a medium-displacement vessel. Our fuzzy math for a medium-displacement sailboat fills in the WSA equation as follows: WSA = 30 x (10 + 6) (.75), and the result is 360 square feet.

Next comes the all-important apportionment of easy versus difficult paint removal. In this case, 85 percent falls into the tough-going regime that equates to four minutes of toil per square foot (0.85 x 360 x 4 = 1,224 minutes of misery). Add in the easy scraping (0.15 x 360 x 0.5 = 27 minutes), and the result is 1,251 minutes, or just under 21 hours of serious scraping. This is unequivocal arm-in-action time, and the ride to the boatyard, coffee breaks, and chats with sistership owners, stops the clock.

Chemical paint removers, a large crew, or true friends can soften the blow, and so can a more deteriorated surface. If 70 percent of the bottom paint has a cornflake-like look, it will allow a thin bladed putty knife to effortlessly separate it from the hull skin, and a very different labor picture arises. Run the numbers, and you’ll find that in this scenario, 9.3 hours of toil would strip away the residue. In short, it’s not the bad spots you need to worry about, it’s where the paint looks good that causes all the problems. This is why procrastination rules, and we tend to postpone bottom paint removal in favor of spot prepping and feathering in the bad spots. At some point, it’s time to bite the bullet and tackle what’s been pushed down the road.

Temperature, dwell time, and sharp scrapers are as important as picking the right concoction.

Our foray into sodablasting follows years of testing several different ways to remove bottom paint. Although you can simply attack the bottom paint with a power sander (an 8-inch sander-polisher is probably the most common tool for this purpose), this approach is messy, back breaking, and can expose the do-it-yourselfer to various health hazards. It can also lead to dings and divots in the gelcoat caused by overzealous sanding. Many yards prohibit do-it-yourselfers from sanding antifouling, or offer specific guidelines on how it can be carried out—often prescribing a chemical stripper to help contain the paint residue.

Chemical paint strippers break down the paint’s adhesive bond on the hull and make it easier to scrape down to clean substrate that can be repainted. You can choose different strengths of stripper depending on the job at hand, or you can vary the strength by leaving the chemical stripper on the hull longer.

Over the past 10 years, Practical Sailor has looked at a wide range of high-strength strippers developed specifically for removing marine paints—antifouling paints in particular. After experimenting with concentrations, dwell times (the amount of time you leave the stripper on the hull), and ambient temperatures, we found we could greatly reduce the scope of a paint removal project. However, we still came to the conclusion that there had to be a faster, easier way to remove bottom paint.

The Tests

In November 2006, we looked at nine different marine strippers. Back to Nature Ready-strip was our Budget Buy, and Franmar Soy-Strip was our Best Choice. Two other products, Pettit Bio-Blast and Back To Nature Aqua Strip were Recommended. A past winner in PS testing, Peel Away Marine Safety Strip from Dumond Chemical, did not land among the top contenders. Dumond Peel Away Marine Strip II, Sea Hawk Marine Paint Stripper, and Interlux Interstrip 299E were other products that did not make the final cut.

Not surprisingly, most of the strippers touted their ecofriendliness. Since the mid-80s, boatyards have been under pressure from both state and federal regulatory agencies to contain the toxins and heavy metals contained in bottom paints; chemical strippers helped meet that goal. The newer strippers also were water-soluble, simplifying cleaning and reducing volatile organic compounds leaking into the atmosphere.

In 2008, we updated our 2006 report with a test in slightly cooler temperatures—65 to 72 degrees versus 85-plus degrees in 2006—and on a more challenging overhead, horizontal surface. The test pitted the Franmar Soy Strip against a new, water-based product from Dumond, Peel Away Smart Strip. In that comparison, the Peel Away Smart Strip performed slightly better, although neither product did particularly well removing multiple layers of bottom paint. In this test, testers found that the dwell times could be sped up by covering the strippers with clear plastic to prevent evaporation.

In March 2009, we raised the stakes. Not only did we want to remove an antifouling paint, we also wanted to peel off a 25-year-old Interlux Interprotect epoxy barrier coat, that was beginning to fail. For that round, we selected “the best of the best” chemical paint removers from previous tests: Soy-Strip by Franmar (best in 2006), Dumond Chemicals’ Peel Away Marine Safety Strip (best in 2000), and Peel Away Smart Strip (best in 2009). Because of the longer dwell times needed to soften the epoxy coating, testers tried them with and without a covering: Peel Away’s proprietary paper for the Dumond products and a 1-mil clear plastic for the Franmar stripper. Testers found that the Peel Away Marine Safety Strip—with its thick, creamy consistency— was the most effective for heavy-duty epoxy-paint removal. The Franmar Soy Strip also worked, but not quite as quickly. The testers concluded that using either stripper alone, without covering the product to extend the dwell time, would not be effective against epoxy.

Incredibly stripped a ’66 full keel 30′ Pearson Coaster, months of very aggressive grit 24/36 many weeks of grinding, faring, multiple coats (5) of Interluxe barrier coat.

Currently acquired a ’78 Pearson 323 Sloop. Modified keel, no previous barrier coat that has multiple coats of bottom paint with many irregularities that need removal.

It was interesting when you talked about how soda blasting is the recommended means of paint removal from the bottom of boats. I would imagine that soda blasting could also be used to remove mold and other kinds of water damage that can build up. It would be interesting to learn more about the ingredients that are put into the material that is sprayed onto the boats.