Cooking at sea has never been easy and is usually looked upon as a dull, but necessary task. Nothing can spur the queasy stomach to open rebellion more effectively than going below to a hot, stuffy galley to prepare – ugh! – food. Why would anyone in his right mind try to prepare a meal at a 30′ heel while the rest of the crew enjoy a sail on deck? The term, ‘slaving over a hot stove’, takes on new meaning.

288

Yet, the cook is a vitally important member of the ship’s crew, and it is not an easy job. Whether on a delivery, racing or long distance cruising, a non-stop passage on your boat means no nipping out to buy that missing ingredient: there are no supermarkets at sea! So remember, the moment you leave the dock you’d better be sure you haven’t forgotten anything. If you like acronyms, here are two secrets to success that you can remember: The Six P’s, and MAMAS Theory.

Planning

The Six P’s are: proper prior planning prevents poor production.

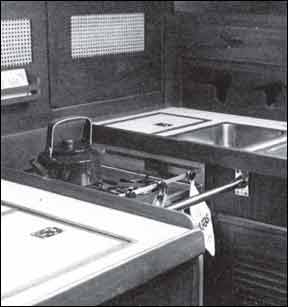

First make an inventory of the galley. Examine the stove and the capability it offers, ie, number of burners and oven, is it gimbaled, does it have fiddles, and how long will the fuel last. Next make a list of the pots (use one size larger than on land to eliminate spillage): frying pans, tea kettle, coffee pot, pressure cooker and/or dutch oven. Then inventory the utensils. Double up on several items such as a potato peeler, small cutting board, paring knife, can opener, plastic collander (won’t rust), and pot holders.

Assume that you will encounter nasty weather and possibly with not reach port on the ETA.

Remember you will be needing to do everything by hand, so wisk and mixing spoons are a must. Be sure to count the bowls, plates, cups, mugs, forks, spoons and knives.

Thank goodness for modernization. With cured, smoked, and canned meat, along with freezers and refrigerators, we are able to enjoy a variety of food at sea. Whether you use wet or dry ice, refrigeration and/or freezer, it is important to understand their limitations. First, measure the amount of space available. Estimate the length of time the ice will last. When using a frig/freezer system you would be wise to anticipate a breakdown.

No matter what kind of cooling system you have — or don’t have — it is always helpful to stock the perishables at the last moment, either cold or frozen, if possible. Putting warm items into a ship’s cold box or freezer constitutes a colossal waste of ice or power to cool down the food, if, indeed, it ever does get cool. It may be simply beyond the capacity of the icebox or refrigeration system to cool many warm items, especially in a warm climate, or it may take it so long that the food manages a fair amount of deterioration while the moderate temperatures last.

Entrees prepared, wrapped in foil and plastic, and frozen ahead of time work for you in two ways. First, they contribute to the cooling of the cold box. Second, they reduce preparation time, since they can be simple removed before a meal and heated without even taking them out of their container. Freeze everything which can be frozen, such as milk and butter, to add their cold to the box.

288

The next step is to explore the storage space. Check the bilge, under the settes and galley lockers. You may also want to ask the captain if there is any space available which is not being used for boat gear. List every available space, noting the size and if it is wet or dry. This will be an important consideration when you begin to stow you supplies. Basic necessities such as bread, eggs, onions, potatoes, etc, should be stowed in a cool, dry space, easily accessible. Other items which come in boxes should be rapped in plastic before stowing. Canned food should be labeled with waterproof marker and stowed in areas where they will not be sitting in water: they do rust. You can check the integrity of the can by firmly pressing down on the lid with two thumbs. If the lid stays concave you then know the vacuum seal has been released and the food in all probability is spoiled. It takes only a tiny pinhole to allow seepage. If you need to make use of the bilge for food storage, plastic containers are great, but try to keep the lids out of the water. Glass items of any type should be avoided in the galley.

The cook, in fact, is in control of the general health and attitude of the entire crew. Give it your best!

Finally check for safety. Is there a strap to keep you from falling to leeward or a secure bar to prevent falling into the stove? Is the fire extinguisher designed for stove fires and located near by? Is there a fresh air vent over the galley for when the boat is closed up tight: does it leak in rain and heavy weather? If you are a racing cook, plan to wear sea boots and foul weather pants in the event something hot should spill from the stove. The cruising cook, too, should wear more than a string bikini.

By counting the number of crew members, number of days passage and adding snacks, you should have a fair idea of the volume of stores required. Assume you will encounter nasty weather and possibly will not reach port on the ETA. For offshore passages, or cruising to remote areas, we suggest taking two extra weeks worth of nonperishable supplies, unless you are racing and weight is a problem.

MAMA’S Theory

When you begin planning for the passage remember MAMA’S theory. Meals + Appetite + Morale + Appreciation = Success a guaranteed formula for planning.

Meals must be carefully planned. Knowing how long you will be gone, write out the daily menu. Include the amount of food needed to complete each meal. This will be your shopping list so remember to write every item down. Make the menu simple with minimal amount of galley prep work, but with enough variety to keep the crew from becoming bored. The best recipes are easy to read, basic ideas and easy to prepare. There are numerous marine cook books on the market, however the old shoreside stand-bys are the best, such as Betty Crocker or Better Homes and Gardens.

Appetite will vary among the crew members. If there are crew members with whom you have not sailed before, ask them about allergies, likes and dislikes. We have found that crews generally have one of two reactions at sea. They either develop a hefty appetite or prefer to eat small light meals with snacks in between, Fresh milk, vegetables and fruit requiring refrigeration should be rationed by the cook for two reasons: first, for nutritional value and roughage; and secondly for morale.

Morale is something the cook can control pretty completely during the passage. By doing simple tricks such as serving fresh food out in the middle of nowhere, you will find the crew’s spirits lift in the worst of weather. A cook who takes the time to make interesting meals with varied color, texture and presentation, will give the crew a welcome break from the daily routine rather than an ordeal to be tolerated. This does not mean that each meal needs to be different. With a little creativity, Saturday’s dinner can become Monday’s lunch, saving food and labor.

Appreciation works in both directions. The cook will be pleased to see the crew gobble down every bite and the plates return to galley clean, and the crew appreciates your galley efforts, and you.

Success is your goal. Being the ship’s cook is not a position to be looked down upon. It is, in fact, very important, for you are the one in control of the crew’s general health and attitude. If you view the position in a negative manner, your crew will respond in similar fashion with their on-deck performance, and you may be known as the crew member who didn’t pull his/her own weight. The cooks position is a grand position, one to be respected, challenging and fun. Give it your best.

-C. Dwyer