At its most basic level, my goal as a sailor is pretty simple: keep my neck above water. Speed, comfort, progress toward a destination are nice, but if I need gills to achieve any of these, something is amiss. And since an upside-down boat tends to interfere with this modest ambition, I’d say our recent obsession with stability is justified.

This is far from our first foray into this topic. Shortly after the 1979 Fastnet race disaster, in which 15 sailors died, Practical Sailor embarked on a series of articles on sailboat stability. The racing rules of that era had resulted in designs that were quicker to capsize than their heavier, more conservatively proportioned predecessors, and we needed to explore why.

Since then, the lessons of Fastnet have been absorbed by the design community, culminating with the CE Category system and formulas used by various racing bodies like the Offshore Racing Congress to evaluate a boat’s fitness for the body of water where it will sail. But it’s clear that the tools we use to measure stability, and the standards we’ve established to prevent future incidents are still imperfect instruments, as we saw in the fatal WingNuts capsize in 2011. And in the cruising community, where fully equipped ocean going boats hardly resemble the lightly loaded models used to calculate stability ratings, we worry that the picture of stability is again becoming blurred by design trends. This video gives some insight into the dockside measurement process for racing boats.

Last month, we examined multihull stability, including an analysis of several well publicized capsizes. One of the key takeaways from that report was the significant impact that hull shape and design can have on a multihull’s ability to stay upright. Another key observation was the distinction between trimarans and cats, and why lumping them together in a discussion of stability can lead to wrong conclusions. As we pointed out, many of the factors that determine a multihull’s ability are related to hull features—like wave-piercing bows—that are difficult to account for when we try to calculate stability.

This month, we take another look at monohull stability. This time it’s a formula-heavy attempt to tackle the conundrum that many cruising sailors face: How can I know if the recorded stability rating for my boat reflects the reality of my own boat? Or, if there is no stability rating from any of the databases, like the one at US Sailing, how do I assess my boat’s stability?

Stability Resources

If you are unfamiliar with this topic, I’d recommend reading three of our previous reports before digging into this month’s article. “Dissecting the Art of Staying Upright” and “Breaking Down Performance,” both by PS editor-at-large and safety expert Ralph Naranjo, take a broad view of sailboat design elements and how they applies to contemporary sailors. Nick Nicholson an America’s Cup admeasurer and former PS Editor, also offers a succinct discussion of stability in his article, “In Search of Stability,” which I recently resurrected from the archives. (Nick, by the way, is no relation to the current editor.)

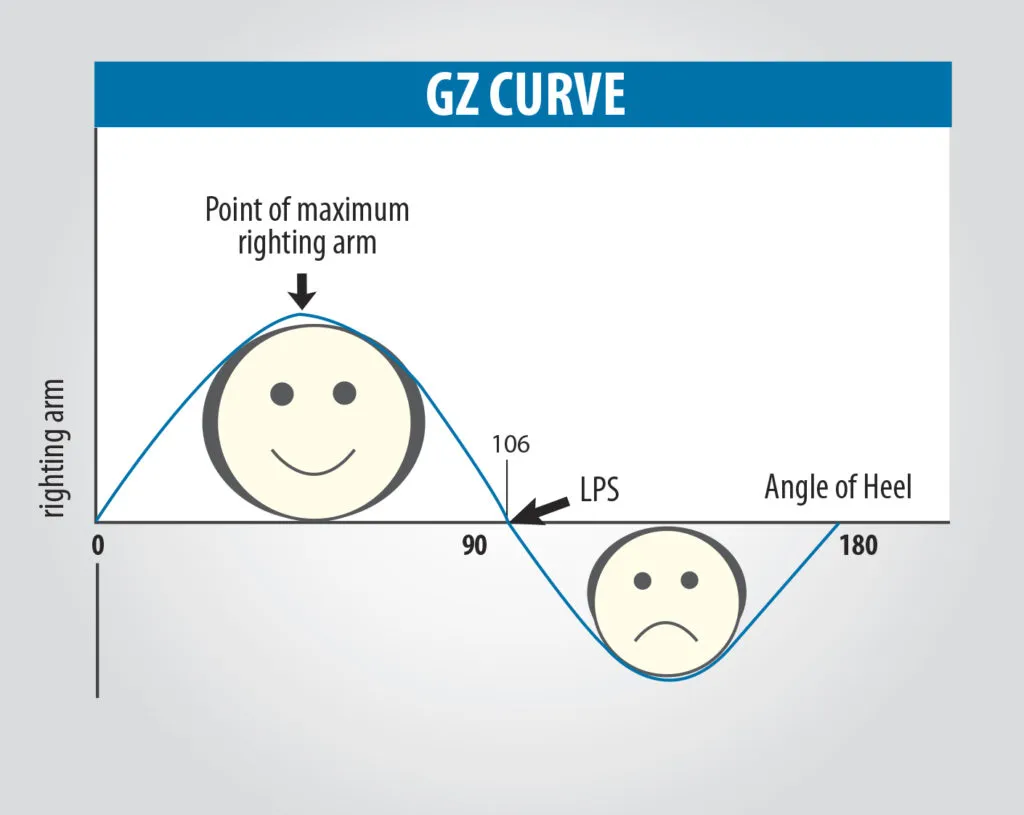

When we’re talking about stability, the essential bit of information that every sailor should be familiar with is the GZ curve. This graphic illustration of stability highlights the boat’s maximum righting arm, the angle of heel at which resistance to capsize is greatest. It also illustrates the angle of vanishing stability (also called the limit of positive stability), the point at which the boat is just as likely to turn turtle as it is to return upright. Most boats built after 1998 have a GZ curve on file somewhere, and US Sailing keeps a database of hundreds of boats for members. As this month’s article points out, however, the published GZ curve does not always perfectly transfer to our own boats. Nevertheless, it is usually a good benchmark for assessing your boat’s stability ratio—not to be confused with capsize ratio the stability index or STIX.

For a succinct discussion of stability ratios (see below), Ocean Navigator’s excerpt from Nigel Calder’s Cruising Handbook lays good groundwork for the theory. If you really want to dive into the topic, Charlie Doane presents a good overview in this excerpt from his excellent book “Modern Cruising Design.” Doane, like many marine journalists, relies greatly on the work of Dave Gerr, former director of the Westlawn Institute of Yacht Design and now a professor with SUNY Maritime Institute. Gerr’s four books “Propeller Handbook,” “The Nature of Boats,” “The Elements of Boat Strength,” and “Boat Mechanical Systems Handbook,” all published by McGraw Hill, illustrate Gerr’s rare talent for taking complicated topics and making them comprehensible and fun to read.

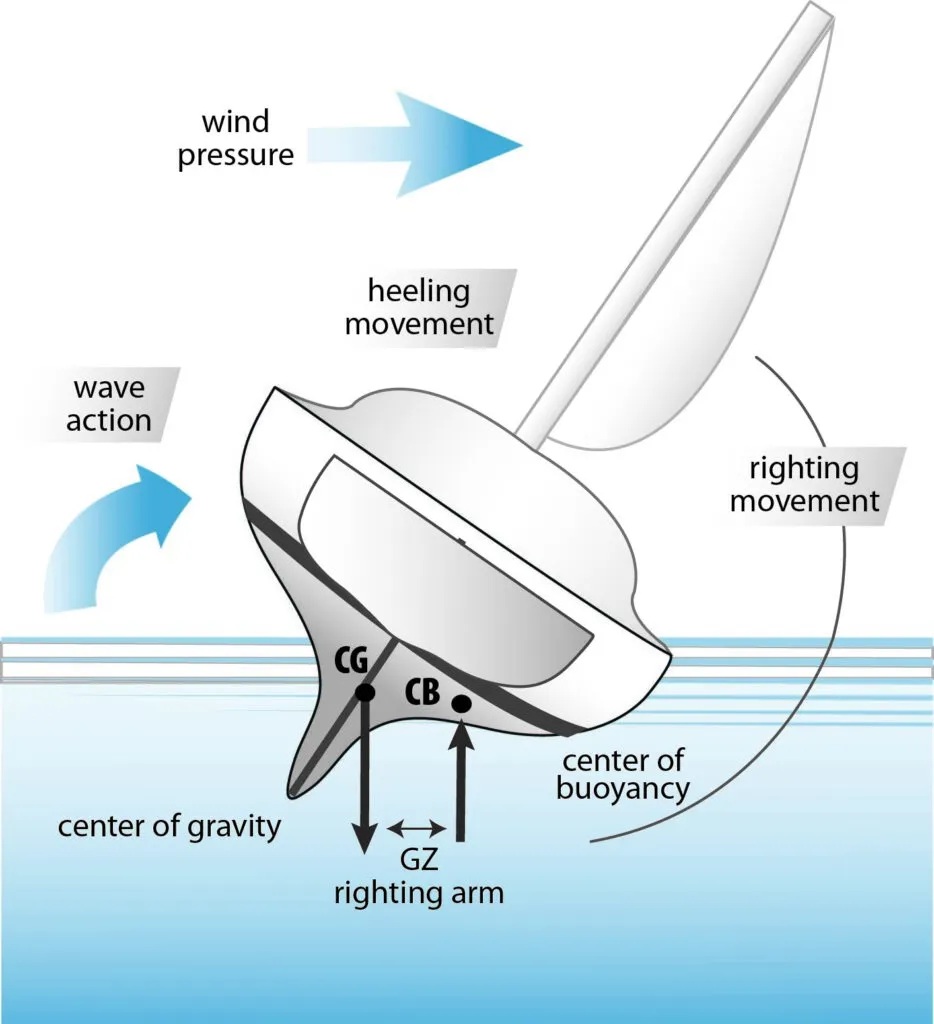

arm (GZ). The righting moment (RM) is the torque developed at specific angles of heel (the hull resists the heeling moment: RM = GZ x displacement. (Illustration by Regina Gallant)

The GZ Curve

Shaped like an “S” on it’s side, the GZ curve illustrates righting lever. The high peak represents a boat’s maximum righting arm (maxRA), the point at which the forces keeping the boat upright (ballast, buoyancy) are strongest. The lowest valley, which dips into negative territory, represents the minimum righting arm (minRA), the point at which these forces are weakest. The curve also clearly delineates the limit of positive stability (LPS, also called the angle of vanishing stability), where the curve crosses into negative territory. Generally speaking, an offshore sailboat should have an LPS of 120 degrees or more. As Naranjo puts it, “It is this ability to recover from a deep capsize that’s like money in the bank to every offshore passagemaker.”

-

- The “smiley face” area under the positive portion of the GZ curve (the positive energy area, PEA) should be compared with the area under the negative portion, NEA (depicted with frowning face). The higher the ratio between the two, the more seaworthy and less likely a monohull is to capsize, and the more likely it will recover from a deep knockdown. According to Nigel Calder, a cruising boat should have a PEA:NEA ratio greater than 3:1—although, as we point out in the article, the ratio is but one element of evaluating seakeeping ability. He estimates that his Pacific Seacraft 40 has a ratio of 10:1.Transferring the curve to graph paper can help calculate the respective “energy areas” – or you can use a formula that Gerr recommends:

Positive Energy Area (PEA) = LPS x maxRA x 0.63

Negative Energy Area (NEA) = (180-LPS) x minRA x 0.66

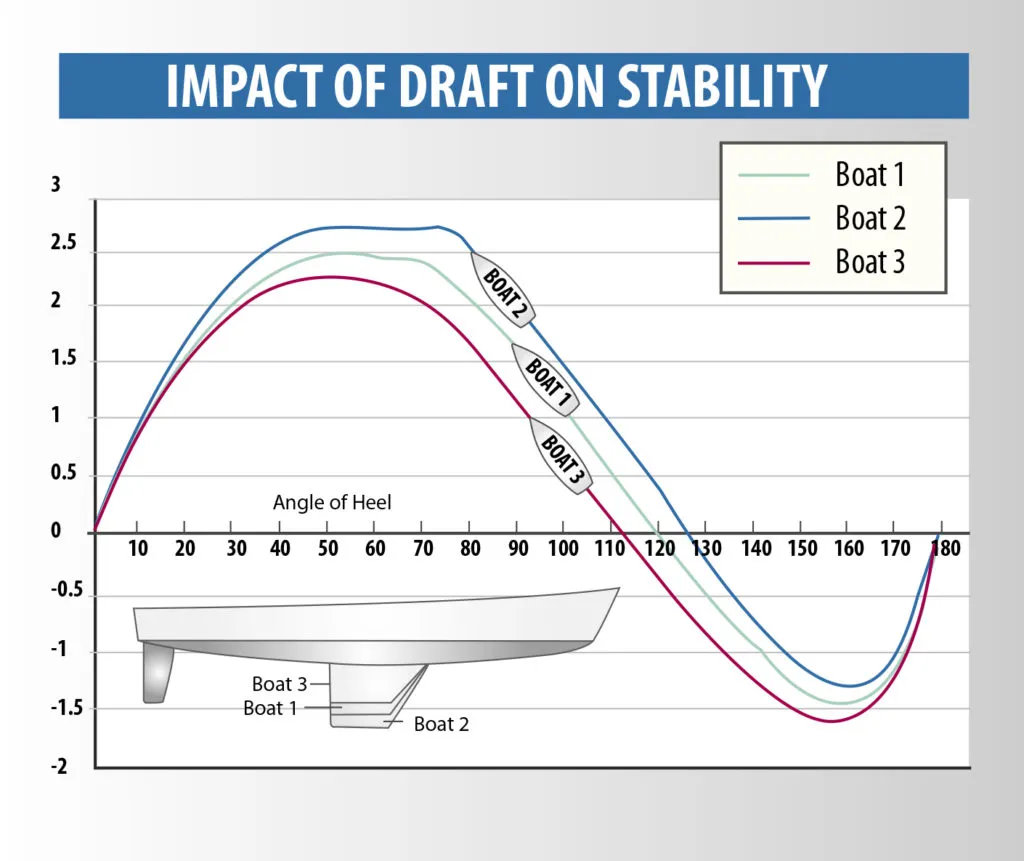

- Notice how lowering ballast lowers the center of gravity (CG) and increases a vessel’s limit of positive stability. In these examples, three identical 30 footers with the same amount of ballast, but differing keel stub depths, alter their draft and GZ curves. Boat 1 (5’ draft), Boat 2 (6’ draft) and Boat 3 (4’ draft). Note that Boat 3, the shoal draft option, has the lowest LPS and Boat 2, has the deepest draft, highest LPS and will sail to windward better than the other two boats.Editor’s note: One would think that with all the reporting we’ve done on stability, we’d be able to label a GZ curve correctly, but in the print version of the March 2021 issue we have mislabeled the curve. I apologize for the error. Sometimes, despite our best efforts, our own GZ curve turns turtle during deadline week. The correct version of the curve appears in the online issue and in the downloadable PDF. If you have questions or comments on boat stability, please feel free to contact me by email a practicalsailor@belvoir.com, or feel free to comment below.

- The “smiley face” area under the positive portion of the GZ curve (the positive energy area, PEA) should be compared with the area under the negative portion, NEA (depicted with frowning face). The higher the ratio between the two, the more seaworthy and less likely a monohull is to capsize, and the more likely it will recover from a deep knockdown. According to Nigel Calder, a cruising boat should have a PEA:NEA ratio greater than 3:1—although, as we point out in the article, the ratio is but one element of evaluating seakeeping ability. He estimates that his Pacific Seacraft 40 has a ratio of 10:1.Transferring the curve to graph paper can help calculate the respective “energy areas” – or you can use a formula that Gerr recommends:

Thanks for this reminder, another error has crept into the diagrams I think. The yacht seems to have 2 CBs and no GG.

I noticed that also, Halam. With no center of gravity and all buoyancy that boat will never sink. Of course, it could be at rest upside down also.

The link to the US Sailing database is pointing to a different place than I think you intended. It is not the database of boats, but rather information on curve calculation and definitions.

Hi Darrell, sorry to be the bearer of a correction, but it looks like the CG is labeled as CB in the first graphic.

As far as I know, a rule of thumb is that a sail boat can tolerate cross breaking waves not higher than her max beam. Is it true?

It often amuses me to see the many crew sitting out on the gunwale of a keel boat, (monohull) as the righting effect must shorely be minimal. Especially when compared to a small racing trimaran. It does help the ‘Gyration’ as shown in the Fastnet tragedy. Even the ‘Skiffs’ have ‘racks’ out the side, & I’ve seen all sorts of ‘keel arrangements’. They just haven’t put ‘floats’ on the end yet. I’d love to see someone do a ‘stability kidney’, as Lock Crowther said (all those years ago), the the righting, (capsizing force is 35? degrees off the bow. Thought provoking? not antaganistic. Keep up the good work, and thanks ‘B J’.

A useful view of stability is to consider where the energy to resist capsize is stored. As a boat rolls, the center of gravity is also raised with respect to the center of buoyancy, so the weight of the boat is lifted, at least through some angle (as long as the GZ is positive) and energy is stored as a lifted weight. This means that a stability incident is exactly equivalent to rolling a ball up a hill; it will always roll back down until it passes over the top of the hill. This is why most commercial and military stability standards use “righting energy” for at least one criteria. The ISO 12217-1 standard for coastwise and oceangoing power boats requires at least a minimum absolute energy and an energy ratio exceeding a nominal overturning energy of combined wind and wave (similar to the IMO standards for cargo ships and 46 CFR 28.500 for fishing vessels).

Can anyone comment on the stability of Volvo Ocean Race boats? While various mishaps have occurred over the years, I don’t believe any of them have capsized and remained inverted. VOR boats are nothing like the Pacific Seacraft and similar designs from more than 50 years ago, yet they seem “safe”.

Does anyone know why? Size, keel depth and weight, modern design tools?

Good and useful article, particularly to someone considering buying a new or used sailboat. As an add-on to the effect of draft, I would add that most, if not all, builders increase the weight of the keel to try to compensate for the reduction of righting moment with the reduction in draft. I recommend to readers Roger Marshall’s outstanding book entitled “The Complete Guide to Choosing a Cruising Sailboat”. Chapter 3 “Seaworthiness” and chapter 10 “Putting it All Together” are worth the cost of the book many times over. Unfortunately the book is getting out of date, it was published in 1999 and many newer sailboats have come on the market.

Mark, thank you for recommending to read Roger Marshall’s book.

May i suggest reading the book, “Seaworthiness the forgotten Factor”. The author (C.J.Marchaj) makes a number of interesting observations about modern boat design (published in ’86, so not that modern). What sticks with me is the notion that one aspect of seaworthiness is how well a person can survive inside the boat in question– deeper keels make for more righting moment but also a snappy roll, for example, promoting incapacitating seasickness. The boat has to be well enough behaved to “look after” the crew.

My boat 40 ft Samson SeaFarer ketch is fairly tender initially but then settles down once the rail is int he water….but I have never had the top of the mast in the water to see if it would recover well.

Since I am not and engineer or math whiz (and don’t want to be!) I wonder if there is a practical way to actually test the stability while on the water. Is there a way for example to pull the top of the mast down to varying degrees/angles and measure the force it takes to do it and use that as a guide to stability. Could that provide some extrapolative certainty to going further around the wheel of misfortune? Crossing between NZ and Australia (45 years ago..) we were knocked over (not my current boat) with the top third of the mast in the water and she righted very quickly (very comforting) – no great mishap except to make the cook go wash the soup out of his hair and confirm all the things we hadn’t tied down…including dishevelled crew.

Cheers

Gerry

Can someone please link to the article referenced above on multihull stability? I’ve searched, but cannot find it. Thank you kindly!

I have the same inquiry as Jet. I can’t find the Multihull article. Please advise ASAP!

The link in the 4th paragraph works for me:

https://www.practical-sailor.com/sailboat-reviews/multihull-capsize-risk-check

Couldn’t find this link either. Thanks.

Is it possible to get a link to the USSailing boat database, or some hints on where to find it on the site? The current link just goes to ussailing.org.