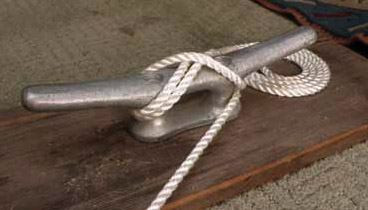

A couple of photos in the July issue of Practical Sailor prompted a deluge of emails regarding the proper way to cleat a line. The articles focus was a test of chafing gear, but what compelled many readers to comment were the accompanying photos of cleated dock lines-including our cover photo.

William Solberg, a longtime subscriber from Los Angeles, was among several readers who pointed out that the cover photo (which was reproduced again in a smaller size with the article) was not consistent with the instructions given by respected sources such as “Chapmans Piloting and Seamanship“ and “The Complete Riggers Apprentice”by Brion Toss.

By Ralph Naranjo

One of the offending photos (right) was a photo demonstrating a poor cleat design that invited chafe. This was one of many boat show photos we had on file for our article on a disturbing trends in cleat design and installation. That particular knot was found at a boat show-Miami, as I recall. The belay is a variation of what could be called an anti-Galligan hitch (from the term anti-Gallican, or anti-French). It would likely do the job, but it was obviously sloppy and unseamanlike, and we should have pointed that out in the caption.

Clifford Ashley, author of the encyclopedic knot book, “The Ashley Book of Knots,” traces the name “anti-Galligan” back to the Napoleonic Wars and says it is the most polite name I know for a left-hand belaying pin hitch. It doesn’t take much searching to find examples of this belay on the waterfront or the Web. We found one posted by Steve Dashew, boat designer and author of the “Offshore Encyclopedia.” (I wonder how many emails he has received.)

By Ralph Naranjo

The more interesting cleat debate surrounds our photo of a three-strand line and chafe gear featured on the cover (right). The chief complaint regarding this photo was that it showed one complete wrap around the base before beginning the figure-eights, and finally-a neat half-hitch that aligns the diagonal of the previous wrap.

As most of our critics pointed out, several trusted sources do not recommend a closed loop-one that passes under one of the horns twice-before beginning figure-eights. The chief problem with having a complete loop for the first wrap, from what I can find, is that it could cause the line to jam against its own standing part, making it harder to release. This seems unlikely in the photo example, although I could imagine it being a problem in some situations.

Courtesy of William Solberg

Solberg supplied an example of the correct cleat according to Chapmans, Toss, and others (right). In this example, the line passes under each of the horns once and then the figure-eights begin. To my knowledge, this is the most common textbook example. To confuse matters, however, the textbook descriptions of this belay refer to the first wrap and one complete turn or one full turn, even though the loop never really closes. Animated Knots offers a video and discussion of the conventional view regarding the first wrap.

However, there are a number of sources including “Drapers,” the British Yacht Association, Hins “Knotting and Splicing,”Peter and J.J. Islers“Sailing for Dummies,” and others that show a full turn around the base of the cleat. Given that many of these sources are British or European, I am beginning to suspect that the origin of the discrepancy could be more of a cultural issue than a practical matter. Interestingly, Ashley, an American, offers a belay (#1645, p. 284 of”The Ashley Book of Knots”) with a turn beneath just one horn before making a half-hitch around the other-a belay that seems too slippery for modern braided ropes.

From my perspective, the cleat shown on our July 2011 cover is fine for most jobs, the exception being perhaps a case in which there is some upward load (toward the horns), or the cleat is too small, making a jam more likely if you make a complete loop around the base. The main advantage of this complete closed loop, as I see it, is that it can be somewhat faster to secure the line, but this also would make it slower to cast off.

One thing to keep in mind is that a uniform cleating procedure is important so that a line can be cast off quickly in the dark of night in an emergency. If you have a left-handed member of your crew who is starting with counter-clockwise wraps, for example, it might cause a problem down the road-or down the rode, as the case may be.