My dream to sail from New England to the Bahamas involved a trip down the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (ICW), also known as “the ditch” or the inside route. These are my lessons as an ICW first timer taking a 32-ft. sailing catamaran more than 1000 miles south on the ICW, sometimes solo. After sailing from Rhode Island to the Chesapeake Bay in the late summer of 2023, I planned to take the inside route from Norfolk, Virginia to southern Florida. Then, I wanted to do the shortest day hop over to the Bahamas.

This journey was my first time cruising for months at a time. Shortly before I untied my lines, I realized I might never feel my boat and I were completely ready, but that I was going anyway. I went to live-aboard sailing school for my 40th birthday, and I’d been sailing part-time on my catamaran for several New England summers. For me, part-time meant most summer weekends and a few weeks each summer. When my partner and I split before we realized our shared dream to sail to the Bahamas, I decided to go solo. Friends and family—mostly non-sailors—joined me for parts of the trip. My new partner—with minimal sailing experience—also joined me for part of the journey, and I was trying to give him a good impression of boat life. I wanted to do the ICW because I’d never done a night passage, and I preferred to anchor every night with an occasional stop in a marina. The ICW is perfect for this kind of coastal cruising and gave me the chance to go all the way to the Bahamas with a few dozen day hops.

TIMING AND ROUTE

I’ve never been one to follow the crowd, so it was fitting that I was both early and late on my journey south. I entered the ICW at mile marker (MM) 0 in Norfolk on October 1 and spent a couple of weeks heading south into North Carolina. This was the early part—I was ahead of the mass migration south. Then I left my boat in mid-October for two and a half months while I went back to land to have surgery and celebrate the holidays with my family. On New Years, I returned to my boat in North Carolina and hustled south to get out of the cold. It was ice-on-the-unheated-boat-in-the-morning cold. Now, I was late—most boats had already wisely headed south. The joy of being early and late was that I almost always could find a dock when I wanted one, and there was less traffic passing me. In January, there was almost no traffic in the Carolinas.

In mid-February, I crossed to the Bahamas from No Name Harbor on Key Biscayne. So my time moving south on the ICW from mile marker 0 at Hospital Point in Norfolk to mile marker 1018 at Lake Worth in Palm Beach took about seven to eight weeks. I then moved south outside in the Atlantic to prepare to cross the Gulf Stream to Bimini, Bahamas from Key Biscayne in southern Florida. When I returned from the Bahamas in April, I crossed from Bimini directly to Lake Worth (MM 1018) and spent another two weeks heading north to Georgia on the ICW. I spent about 10 weeks on the ICW in total over seven months. The seven months included a two and a half month break from the boat and two months in the Bahamas.

My goal was to day-hop from place to place about 150 miles per week, and this was realistic for my 5 knot sailboat, most of the time. That meant five days per week at 30 miles per day. I rarely moved more than 50 miles in a day. I found 30 miles fairly comfortable, and 50 miles a stretch, especially when I was solo. On days I didn’t move, I either explored on land, caught up on remote work, fixed the boat, or I found myself hiding from wind or weather that made travel, even on the ICW, uncomfortable.

People new to the ICW should know the first day on the ICW when heading south is among the hardest of the first 1000 miles. My first day had eight moving bridges, a lock, and the only real decision to make about taking an alternate route—either the Dismal Swamp or the Virginia Cut. I took the Virginia Cut. The Dismal Swamp sounded…well, dismal, although I hear it is gorgeous.

Before the trip, I noodled a bit about whether I had enough tankage and whether it would be hard to get provisions and supplies. None of those were a problem. I serendipitously bought almost the perfect boat for the ICW.

TANKAGE AND POWER

I had pretty limited tanks—40 gallons of fresh water, 27 gallons of gas, and a 30 gallon black tank. They were enough. My boat is powered by two Yamaha 9.9 horsepower outboards, so I only used gas, not diesel. I also had a Torqeedo electric outboard on my dinghy that charged with my solar panels. I had just under 600 watts of solar panels and a 320 amp hour lithium house bank on my 12 volt boat. Before this trip, I’d been operating off grid for years—I hadn’t needed to plug into the dock since my lithium and solar upgrade in 2018. Although I carried a little extra gas and water and a generator, I never needed them on the ICW. There were plenty of places to get gas and water and pumpouts, especially if you used the resources available in AquaMaps and the ICW Quick Reference Guide to plan your route a couple days at a time. Getting propane took a bit more planning and research, but was also possible.

SUPPLIES AND PROVISIONS

There was no trouble getting supplies and provisions on the ICW. I found plenty of grocery stores, hardware stores and marine supplies, when needed. I sometimes pre-ordered needed boat parts to a West Marine further along my route. Sometimes, I sent Amazon or other orders to a friend or family member I planned to meet.

I often had groceries delivered to marinas or got rides to the grocery store whenever a car was available. There was no need to load my boat with months of provisions. I was able to shop regularly and similarly to how I would grocery shop on land. My favorite provisioning stop was the Saturday morning Farmer’s Market in Beaufort, SC (MM 540). I also used my folding electric bike and electric scooter to do errands in some places. Sadly, my electric bike disintegrated in the salt air, and I left it near a dumpster in Florida. Some marinas had bikes to borrow, and I enjoyed using them to explore or run errands.

CREW

I spent a couple of weeks solo—mostly in Georgia and northern Florida, and the rest of the time I had one to two crew members. Most of my crew were inexperienced sailors. My most experienced crew joined the last few days in Florida and crossed with me to the Bahamas. Timing crew changes is not always easy on the ICW or anywhere else. I learned to plan for the crew to meet the boat, rather than the boat to meet the crew. Some of my crew made last minute travel arrangements, and others drove to wherever I was. The ICW is easier with crew who can take the helm for a while. However, crew that can’t take the helm safely are not that helpful unless they do a lot of cooking and dishes. Some crew just complicate the trip. That said, I’m grateful to have shared this journey with friends and family who don’t usually explore the world by slow boat, even though I sometimes felt I was single handing with people on my boat.

GOING SOLO

During my solo time in Georgia and northern Florida, I tended to shorten my travel days. When tides, bridges and currents cooperated, I loved to work remotely in the morning, lift anchor after lunch and arrive at my next anchorage before dark and dinner. I preferred to anchor when solo, and would sometimes go a week without setting foot on land or seeing another person. I spent a lot of time steering because the ICW is not straight and can be quite narrow. The most challenging thing about being solo on the ICW was picking spots in a straight section where I could leave the helm on autopilot and take a bathroom break.

RUNNING AGROUND

Yep. It happened. There is a saying that if you haven’t run aground, you haven’t been down the ICW. I ran aground not just once…but three times. I never ran aground in the ICW or on one of Bob’s tracks. All three times were relatively minor bottom kisses as I reentered the ICW after being in a side channel or marina, and I was outside of any marked channel. All three times, I was able to back off without assistance, and my only damage was taking a bit of bottom paint off my starboard hull. Twice I misread an unconventional marker while distracted by something else, and once I was circling outside of the channel waiting for an opening bridge too close to shore. As long as I stayed in the channel and near Bob’s tracks, I had no problems with water depth.

DID I REGRET GOING THE SLOW ROUTE? NOT AT ALL!

Did I sail on the ICW? Not much. I mostly motored and occasionally motor-sailed with just a headsail. My boat returned to being a real sailboat when I went outside into the Atlantic Ocean between Lake Worth and Fort Lauderdale. This was a great spot for me to exit the ICW. Going inside on the ICW from Lake Worth south to Fort Lauderdale would have involved timing more than 20 moving bridges in one day. No thanks. Getting my mainsail up, turning my motors off, and sailing south was gratifying after so much time in the ditch, even if it is a beautiful ditch. Once we exited the Lake Worth inlet in the dark—my first time moving my boat at night—there were very few things to hit.

In contrast, there were lots of things to avoid hitting in the ICW: crabpots, low bridges, other boats, sunken boats, shifting sand bars, floating trees, standing trees, tree stumps, broken dock parts, navigational markers, swimming snakes and manatees, among others. The most surprising one was a swimming deer in the Pungo Canal. There had been many floating logs and stumps in that section, and I first thought a tree stump was sticking out of the water in the middle of the channel. Then I noticed it was moving across the channel—I never saw a tree stump do that! Soon, I realized it was a swimming buck with only its head and horns sticking out of the water. We avoided it easily. Bucks don’t swim that fast. Who knew it might be possible to hit a deer with a sailboat??

Would I do the ICW again? Absolutely! It was full of unexpected delights, was a wonderful way to start my first longer term cruising adventure, and was an excellent learning ground. Would I commute over 1000 miles north and south in the ICW in a 5 knot sailboat every year single handed? Probably not. People do it, but I tend to get bored the third time I do anything. Other adventures await.

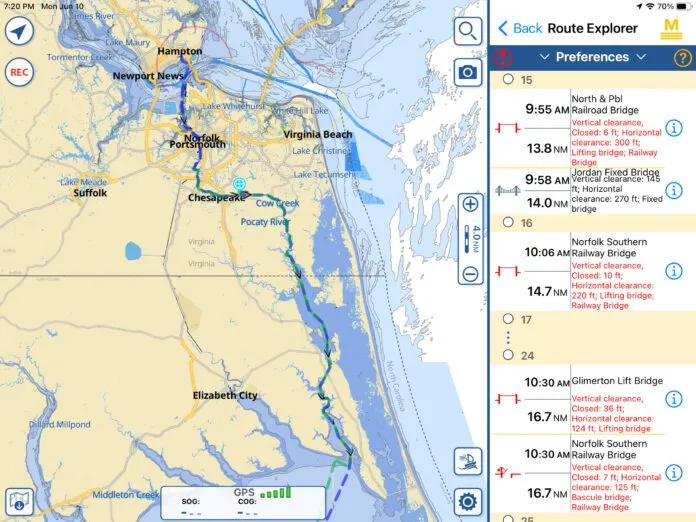

The four resources I appreciated most for my first ICW Navigation were AquaMaps, Bob’s tracks, Wally Moran’s ICW Info Sessions and the ICW Quick Reference Guide from the Boat Galley. Although I have an old Raymarine chartplotter, I decided to get relatively inexpensive updated electronic charts by purchasing an iPad enabled for cell service but without a service contract for this trip. I put the iPad in a waterproof case and loaded the most recent versions of AquaMaps and Navionics on the iPad. I quickly learned that I preferred AquaMaps over Navionics on the ICW because Aquamaps gave ICW mile markers for everything, including my current location, and made timing opening bridges easy. AquaMaps provided estimated arrival times for each bridge based on my current speed and route, and it also has my favorite anchor alarm so far. I can’t stress enough how helpful Bob’s ICW tracks are. Bob is a frequent traveler on the ICW and posts free, updated electronic tracks online, which can be imported into chartplotter software. These are helpful for staying afloat in shallow ICW sections. They are even more helpful when trying to navigate some of the more confusing sections where marked channels go in multiple directions. As my crew sometimes said, “Just follow Bob.” He also has some recommended side routes to easy, interesting stops, and I followed a few of them. I enjoyed Wally Moran’s free webinars about the ICW. My timing didn’t allow me to join his ICW Sail to the Sun Rally down the ICW, but the webinars were informative, and he was very responsive to my newbie questions. Finally, The ICW Quick reference guide from the Boat Galley was also an essential planning resource. I set longer term intentions for my journey—like aspiring to cross to the Bahamas in February—but I planned details only a couple days at a time. I generally wanted to know where I had options to get gas and water next, even if that was a few days away. Lots of things could change my plans, and detailed planning too far in advance was generally a waste of time. Some days I started the day with up to three possible final anchorages for the day, and would stop at one of them when I felt ready. Each evening I sat down with AquaMaps and the ICW Quick Reference Guide to plan the following day. This would allow me to choose our departure time based on tides, currents and bridge openings and set a route in AquaMaps.

4 essential ICW Navigation and planning resources

AquaMaps

Bob’s tracks

Wally Moran ICW Free Webinars

ICW Quick Reference Guide

Interesting article. I was on board a stink potter on the ICW once, and though it was rushed I enjoyed the trip quite a bit. I personally prefer the sailboat way, it was a free ride and wonderful opportunity. I found the sailboat experience described above brings back some memories but also brings a different experience. Thanks

Great article – Thank you! I really appreciate the fusion of practical, crew dynamics and tips on tools.