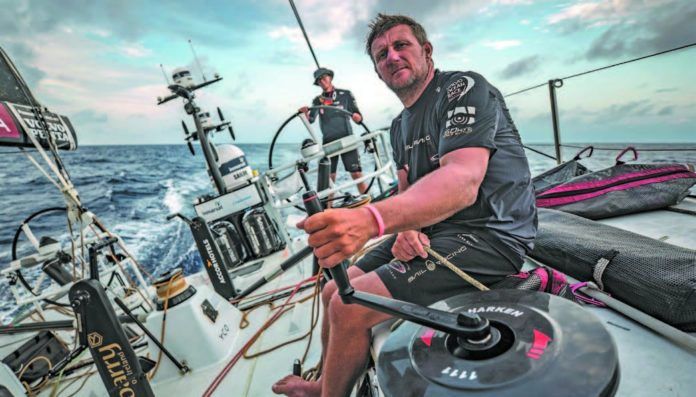

Nearly one year ago, the Volvo Ocean Race boat Sun Hung Kai-Scallywag was deep in the Southern Ocean bound from Auckland, New Zealand to Itajai, Brazil when 47-year-old John Fisher was thrown overboard during an accidental jibe. (Fishers tether was unclipped at the time of the accident as he moved between stations.)

In the frantic moments that followed, the helmsman pushed the MOB button on the ships plotter, a life ring and inflatable buoy was deployed, and the navigator below decks marked a search area on the plotter. After nearly five hours of searching in gale conditions, neither Fisher nor any of the deployed rescue gear was located.

Scallywag had two electronic means to locate Fisher in the water: the chartplotters man-overboard feature, which would record the spot where Fisher went over; and his automatic identification system (AIS) radio beacon. Slightly larger than a penlight, the beacon broadcasts a unique code that identifies the registered owner and broadcasts their location. This is an all ships alert, capable of being received by any boats within range of its VHF signal. If the system were operating as it should, Scallywags navigation system would allow the crew home in on Fisher.

A post-accident analysis later concluded that the MOB button was not pushed for four full seconds (required to activate), and the VHF/AIS antenna on Scallywags mast had been damaged in a storm, rendering it useless.

During much of 2018, Practical Sailor has focused on a more fundamental aspects of safety at sea-staying on board. We’ve looked at tethers, clip-in points, harnesses, the gear that keeps you on board. The 2018 series followed a similar series of investigations into personal flotation devices. In this months issue, we begin a series that explores the last critical link in the man-overboard chain-search and rescue.

In the wake of Fishers tragic loss, the Volvo contracted renowned offshore navigator Stan Honey, who along with Volvos Dan Jowett, produced a technical report on the limitations of AIS, which we expanded upon in our report in this month’s article, “Special Report: “How to Prevent AIS and VHF Antenna Malfunction.” Among one of the most interesting findings of their report is the vulnerability of the PL259 connector, the common standard connector for VHF/AIS antennas. As Honey and Howett point out, these connectors must be well-sealed to perform optimally in the marine environment. There is another option: switch to the more rugged N connectors, long used in the telecom industry. Currently, however, there are very few antenna (one is the Shakespeare V-Tronix MD20N), that use the watertight N-connectors.

Sadly, this is another example in which the marine sector lags behind others when it comes to product development and is slow to adopt innovation from outside the marine market. Standards are critical to ensure consistency of design, but they should not be a drag on proven innovation.

One final note: If you plan to use AIS as part of your man-overboard rescue plan, it is imperative that each transmitter is properly registered and tested with the ships onboard systems. The Newport-Bermuda Race Committee has put together an informative video to help you through this process at

http://bermudarace.com/ais-man-overboard-devices-lessons-learned-in-set-up-and-usage/