Multihulls commonly have net or webbing trampolines that cover the large areas of deck. The trampoline is vital to both performance and seaworthiness. It allows wind and water to pass through and reduces weight at the bow to minimize pitching. A side benefit is the pleasure of lounging on the tramp on a warm summer day.

Early trampolines were expected to last about five years, but improvements in materials and design have increased our expectations. Today, a well-made trampoline can last a decade or longer. As with sails, there are important differences in trampoline construction and materials. Generally, you get what you pay for, and the effort you put into the care and maintenance pays off with longer life.

While this report is aimed mostly at multihulls, monohull sailors will not have to look far to find uses for trampoline material. Built to withstand years of service, the material can serve a variety of purposes wherever low stretch and high strength is needed. We’ve made, pipe berths, lee cloths, and even shelves from scraps of trampoline. To make lightweight shelves, we bonded wood strips to the hull and bulkheads, added eye straps every few inches, and laced in small trampolines with light cord. Not only are these shelves light and strong, but they also provide good air circulation, which prevents mold and mildew.

TRAMP MATERIAL AND WEAVE

Polyester is the most common material for multihull trampolines, although high-strength, low-stretch mesh made from Dyneema is gaining traction. The ideal material and mesh will depend on the application. A large tramp for a cruising cat will be made of heavy, coated mesh with small holes for lounging comfort. A beach cat is focused on light weight and will use a fine mesh, which is also comfortable when you are scampering about on your hands and knees.

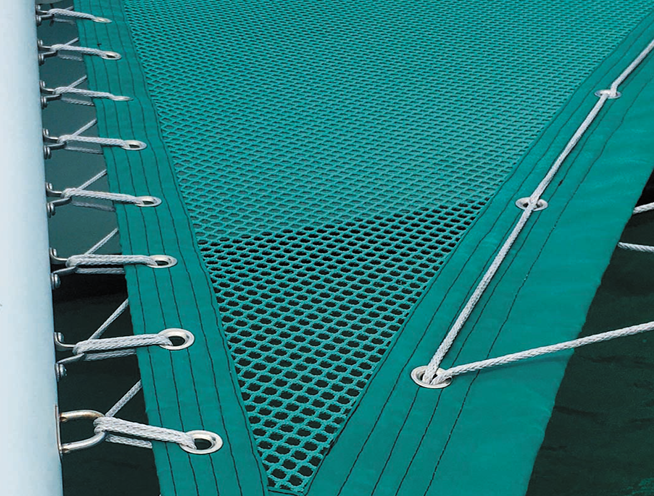

The bow nets of a trimaran have maximum free area (gaps between lacing) to allow the rapid passage of wind and water. The downside of nets with larger holes is that they are uncomfortable when lounging or walking on them with bare feet. Fingers and toes can get caught. The wing nets on a trimaran are located amidship, and typically have less free area, since they will see more traffic. There must still be enough free area for water to pass through, and they must still be made of a lightweight material.

Typical free area ranges from 32 percent for a trimaran wing net of less than 60 square feet, to 70 percent free area for a performance trimaran’s bow net (of any size). A cruising cat with a forward net of 120 square feet should have a net with at least 50 percent free area. The bow net on a smaller cruising cat (less than 120 square feet) will have about 40 percent free area.

Whatever material you choose, resistance to ultraviolet rays is vital. Coatings can help prevent UV damage, just as a sacrificial UV cover protects a furled headsail. The coated tramps we have used on our test multihulls, an F-24 Corsair and a PDQ 32, both lasted more than 15 years in the mid-Atlantic coastal region. Coatings also help prevent chafe caused by abrasion.

Low stretch is important, but without some elasticity, a tightly-laced tramp will sustain enormous tension when a person jumps down or falls onto a tramp. A Dyneema mesh trampoline will add strength, reduce stretch, and may overstress the original attachment points and lacing used to tension the tramp.

Nets made from webbing are the most durable, but they are expensive, heavy, and not very comfortable. Lifeline netting is also a poor choice; most types fall apart in just a few years. Better to have no netting than netting you can’t trust. High quality net material might make sense for the bow section of a trimaran where a very open weave is required, but it will need to be reinforced with grommets and installed in small sections.

If you want to explore the options for tramp materials and design, Sunrise Yacht Products, a major manufacturer of catamaran tramps, has posted a comprehensive guide to tramp materials, design, lacing patterns, and installation. It offers good information that is consistent with our experiences (https://multihullnets.com/Guide/Guide.aspx).

LACING DESIGN

The edges of a trampoline are subjected to high loads when a person falls on them or a wave crashes on deck. Many failures are the result of stress on the attachment point. The typical approach is to use lacing to sew the trampoline into place, alternating “stitches” between the tramp and padeyes or other attachment point on the hull.

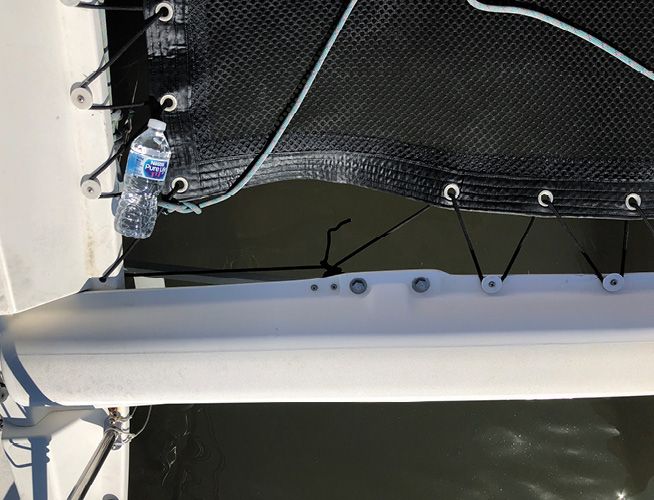

Alternatively, a bolt rope can be sewn along the edge of the trampoline so that it fits into a grooved track on the hull. This eliminates gaps along the edge and gives the trampoline a clean look. In high traffic areas, however, flexing and abrasion is concentrated along the edge, making it more susceptible to wear. We’ve seen several tramps fail along the bolt rope. Additionally, the bolt rope often pulls out of the groove at the corners where loads concentrate. One way to prevent this is to add corner grommets that can be laced to the hull.

The bolt-rope track can also be paired with plastic sliders, just as you see on mainsail luffs. Black sliders resist UV better than white, and we prefer them with metal bails. The nice thing about using a bolt-rope track is that when you replace the trampoline, you don’t have to coordinate the grommets on the new tramp with the attachment points on the hull.

Lacing at the corners can present problems. The lacing here is often too weak, or insufficient to fill the large gap between the hull and the trampoline. Adding extra anchor points and additional lacing pattern can help close these gaps.

When sizing your lacing, remember that diameter of the line relates to the size of the tramp, not the size of the boat. The boat manufacturer, as well as the tramp maker should help guide you to the ideal diameter. The diameter will depend on how much stretch you want, and that will depend on the tramp material. Our Corsair F-24 uses ³/₁₆-inch (4 mm) Dyneema single braid or ¼-inch (5mm) polyester double braid. Our previous test boat, a PDQ 32, used ⁵/₁₆-inch polyester double braid.

Size depends on lacing pattern, which determines the load on each tramp grommet and hull attachment point. Generally, you can use smaller cord with double lace patterns and closer spacing.

The best material for lacing depends on your preferences. The choice is between polyester and Dyneema, both of which have good resistance to UV. Polyester has some stretch, while Dyneema has practically none. The main advantages of Dyneema are strength, chafe resistance, UV resistance, and slipperiness, which virtually eliminates any squeaking in the lacing as load is applied. Dyneema lacing is also slightly easier to tension because it slides more easily through grommet holes. However, that slipperiness means that the lacing can quickly unlace if it is cut. As the Dyneema collects dirt in dusty areas, it can saw into the gelcoat.

Polyester lacing tends to squeak as it ages, but it is less likely to immediately unlace when it is cut. It is also less likely to cut into fiberglass. It will also better absorb shock loads when someone jumps on the trampoline.

INSTALLATION AND LACING

Tramps don’t last forever, and lacings normally require replacement every five years. To replace the lacing, you must center the net with a few loose lashings (heavy cable ties can work) at the corners and at regular intervals along the sides. Begin lacing at one corner and then work your way around in several passes. Don’t use just one length of cord for lacing. Having just a single long cord will make it harder to tension.

A good approach is to use one line for each side. To prevent unlacing, World Sailing, the governing body of sailboat racing, requires you knot the lacing at intervals of every 2 feet. A knot every 4 feet is probably enough, assuming you monitor the condition of the lacing.

Do not over tension. Your trampoline is not a drum. If you over tension, grommets will pull out the first time someone falls on the trampoline. How tight should it be? Bigger trampolines will sag more than smaller ones. In general, the tramp should sag 3-6 inches when someone stands in the center. More stretch is acceptable for trimaran bow nets and other nets that are primarily for safety and infrequently walked on.

The Karver KJH Jaws portable cam cleat can be helpful for pulling lacing taught and a variety of other onboard tasks. You can also be able to make your own “jaws” with an ordinary cam cleat and a block of teak. The cam cleat on climber’s ascender will work the same way. Use a pair of vice grips to lock down the lacing as you begin a new section. If you are simply tensioning existing lacing, a skater’s lacing hook (see photo) is helpful for pulling the laces tight.

Tie off the ends of the laces with a string of half hitches. Be sure to leave some extra lace, because you will probably have to tension or adjust it.

Consider filling any gaps in the lacing with a strip of fabric. Gaps in the lacing, particularly those down the center of the tramp, attract water bottles, sunscreen, and cell phones. We don’t like to cover the lacing because this will hide gaps in the lacing that can trap your foot. We prefer a cover that is laced in place, using the same grommets as the tramp. Perhaps, this is not as pretty, but it’s strong.

Replacing nets on the water, particularly those that lace down the middle, requires installing and partially tensioning the new lacings just a few holes behind the old lacing as you remove it. Keep your weight back from the lacing a little bit and minimize the gap. A pair of vice grips on the lacings (old and new) can keep them from pulling out as you work.

If the tramp attaches with a bolt rope, clean the groove, polish away any burs or sharp spots, and lubricate the groove with McLube Sailkote.

Add additional lashing points as needed. The tramp manufacturer may recommend a minimum spacing of about 6 inches, but if your foot can fit through any gap, it’s too big. Adding grommets means adding more attachment points on the boat. We’ve added grommets to most of our tramps, either for strength or to eliminate hazards. The additional bits of hardware (and required holes) are worth the effort to prevent injury. We’ve gone through gaps several times, and it hurts, sometimes a whole lot.

Sunrise Yacht Products’ website provides extensive installation instructions, covering many net types, shapes, and lacing patterns (https://multihullnets.com/Install/install.aspx).

WORLD SAILING RULES

Offshore Special Regulations (OSR) established by World Sailing requires that the mesh be smaller than 2 inches and that the lacing allows no possibility of trapping a foot, meaning you cannot stick a foot through any opening. On some boats this means adding lacing points in the corners and a pair of laces crisscrossing down the sides.

Folding trimarans like the Corsair often have large gaps between the tramp and the boat to allow the amas to be folded and extended. To close the gaps on our F-24, we laced on mini-tramps made from material used for beach catamaran trampolines. Because these mini-tramps lace under the cross beam rather than directly to the beam, they can be left in place while folding the amas.

The OSR specify that the lacing must not be made in one continuous running length. Intermediate ties are required at “regular intervals” to prevent the lacing from zippering open. The rule does not specify the distance between the tie-in points, but the goal is to prevent an opening that is large enough for someone to slip through should a lace fail. You can use a separate line to make these intermediate ties, or you can seize together two legs of the zigzag lacing every two feet or so.

While minimizing gaps is important to safety, you don’t want the lacing to be too short. The lacing must be long enough to distribute the forces, and to allow for re-tensioning. If the trampoline is too large, you’ll need to trim it down. If it’s too small, you’ll have to fill the gaps somehow. A good fit from the builder is vital.

TRAMP ACCESSORIES

When ordering a new trampoline, you might consider adding a few accessories. In some cases, it is better to add these after installation, so you can better check for correct positioning.

Halyard and sheet bags. Bags can be handy on bow and wing nets for the tails of halyards and sheets. Although the bag can be sewn to the tramp during manufacture, it is often better to either lace the bag to the tramp through the mesh, or install grommets and lash the bag to those. The problem with sewing the bag directly to the tramp is that trampolines stretch in use, and sewing on a bag creates a stiffer hard spot, resulting in stress at the corners, leading to tears. It is better if the tramp can move separately from the bag. Alternatively, you can do as we did, and reinforce the trampoline with a second layer with rounded corners before adding the bag.

Hiking straps. Dinghies and beach cats have straps for hiking out. They are typically made from 2-inch webbing and threaded through large slotted patches. Often the patches have several slots to fit sailors of different heights. Tension is adjusted with a lashing that runs through a grommet on the aft end.

You sometimes see straps on the wing nets of large trimarans, but they are not for hiking out. It’s hard to hold on to a fast, bouncing boat while you are steering or trimming. Falling to windward isn’t the main risk. The straps are primarily there to prevent crew from sliding off the tramp when the boat stuffs into a wave at high speed. They also provide bracing, like the foot braces in many cockpits, to give you more leverage when pulling on sheets or steering. We prefer to helm from the cockpit, for better control.

TRAMPOLINE UPGRADES AND MAINTENANCE

Trampoline failure comes in many forms, and many are preventable.

The most common cause of failure is excessive strain in the corners and high-impact zones.

Stock trampolines rarely have enough lace points to support the stresses at each corner. The result is oversized openings and excessive stress on the grommets. Some corners are also high-traffic areas that see a lot of wear and tear.

The best solution is to add more lacing grommets and more lacing anchors. Sometimes doubling up on the lacing is the answer. This may require adding hardware and drilling more holes. Reinforcing the trampoline itself also makes sense. After all, we reinforce our sails at each corner.

If you decide to add more lashing points, you have a couple of options. Most people just drill holes for new hardware, filling core as needed. If you are adding aluminum track for a tramp with a boltrope, you could try to bond it to the hull, but it will likely fail because aluminum and fiberglass have different expansion properties, which will add stress to the bond. If you don’t want to drill holes in your hull, you can bond a strip of solid ¼-inch prelaminated fiberglass and drill that.

Many heavy-duty nets are coated with a thick waterborne vinyl coating that blocks UV and reduces abrasive wear. Sunrise Yacht Products Net Coating is designed for this purpose, and we are experimenting with some other industrial products. This coating can help a net last decades if the netting is maintained and recoated as needed.

CONCLUSION

Early Hobie Cat and Stiletto owners in the 1970s and 1980s were lucky if their trampolines lasted eight years. The trampolines saw lots of traffic, the material was light duty, and the stitching was weak and had very little UV resistance.

By the mid-1990s however, trampolines had improved. The tramp on our former boat, 34-foot PDQ catamaran, was made with a rugged, vinyl-coated material that was heavily reinforced and had UV-resistant stitching. It served well for 20 years with little sign of wear. We only had to re-lace it once, after ten years of hard use. We added a few grommets in corners, but that was the only modification.

Currently, the trampolines on my Corsair F-24 trimaran are 15 years old and just beginning to show their age, but only where there is foot traffic. We are in the process of re-coating and expect it to last another decade. Nevertheless, we’ll be keeping a close eye on the stitching and if it appears that the netting material itself has become significantly weaker, we won’t hesitate to replace it. As essential as sails or rigging, the trampoline on a multihull is not something you can afford to neglect.

Sunrise Yacht Products sells a coating for DIY use. It is waterborne, comes in a range of colors and is most often applied by roller and brush. The cost is $139 per gallon, $43 per quart.

We considered removing the trampolines for painting, but that would require finding a place to lay the nets and somehow preventing them from sticking to drop cloths beneath them. And we’ve replaced enough tramps to know that re-lacing all four tramps would take all day. Painting in-place seemed far more practical.

Surface preparation is nothing more than a good wash with tri-sodium phosphate (TSP) followed with a thorough rinse.

Mask any bolt rope areas or other places where the tramp runs close to the deck. Hang drop cloths along the hull sides; even if the hull angles inwards, away from the tramp, splatter from the brush and roller will speckle the hull.

First, paint around the lacing with a brush. It’s inevitable that the grommets and some of the lacing will get painted, but only you will notice it. We applied two coats around the perimeter with a chip brush, making sure to cover the vulnerable stitching. The body of the nets received one coat with a long handled mini-roller. The whole project took about two hours, about the same as only relacing only two of the four nets.

Coverage is about 300-square-feet per gallon on previously coated nets and considerably less on uncoated nets, which will absorb the paint. The coating will completely fill in the smaller holes on fine beach cat-type netting, so for that material we would only use it on isolated high wear areas, such as patches under blocks and hems.

Don’t coat a net that has not been well used or at least well-laundered. The fibers on new trampolines will still have spinning oils used during fabrication that will prevent good adhesion. Try to cover as close as possible to the bolt rope, but don’t coat the bolt rope itself—it will jam, and it is not exposed to UV rays anyway.

We saw no need to paint both sides of the woven mesh we tested; the paint ran around the mesh and soaked in evenly. A more solid net, like the one on our former boat, a PDQ 34, might benefit from a light coating on the underside. The coating did not affect the trampoline tension. No lacing adjustments were required.

The recoated nets now look sharp and are shielded from the sun and protected from abrasion in high-traffic areas. We’ll be touching up the coating as needed. We expect it to withstand another 5-10 years of use, perhaps with a relacing in a few years. The net will be slightly slippery when wet, until it wears in a little, but no different from a new tramp. We’ll provide an update in a year or so after the coated tramps have seen more use.