Buried deep within the recesses of the 2020 US Coast Guard reauthorization bill is a requirement that if a boat is planing or moving above displacement speed, a kill switch must be used —with the exceptions of boats over 26 feet, for boats that were not built with a kill switch or emergency stop lanyard, or ESL, in Coast Guard-speak, and for boats with enclosed cabins. With personal watercraft, this is both obvious and practical. If your dinghy is fast enough to plane, it’s fast enough to buck you off the tubes. Most will immediately circle to the right as a result of prop torque, running you over repeatedly in what has been called the “circle of death.”

This rule will not apply to most sailboats propelled by outboards, because very few can exceed displacement speed or plane. A cable kill switch is not practical for most sailors; you can’t move around to set sails and the like. But if a singlehander falls off while working on the bow, with the boat on autopilot, he’s facing a very long swim. And perhaps even large boats could use one more layer of man-overboard protection; anyone can trip over their own feet. Can wireless kill switches provide additional protection? And what does the law say?

Observations

The final regulation has not been written, but alternatives to cable kill switches described in the American Boat and Yacht Council standard A-33 may be permissible. A September 2019 Texas law, for example, allows wireless emergency engine cut-off devices.

Proximity vs. Immersion. The downside of immersion triggering is that if based on conductivity, it must be protected from splash. The downside of proximity triggering is that if the unit has sufficient signal strength to allow transmission through bulkheads and bodies without false alarms, distance alone will not be a sensitive trigger. In fact, all of the manufactures state that the sensor can be moved 50-150 feet from the base station before loss in signal strength will stop the engine. However, if the sensor is submerged, the water provides considerable radio shielding and the alarm is triggered immediately.

Fob location. Man-overboard location beacons must be placed high on the PFD to be effective. Radio signals do not transmit well underwater, and even high seas can block the signal, let alone complete submersion. There have been several cases where submersion was implicated as a reason for signal loss. Thus, the obvious corollary for wireless kill switch beacons is that they should be worn low on the body, perhaps on a wrist or at the waist. Mounting high on the PFD could defeat the function. The Autotether is based on immersion and is probably less sensitive to this.

Wireless kill switch vs. Locator beacon. Kill switches won’t replace locator beacons. The primary function of a kill switch is to keep a dinghy or small boat from spinning around and running you over, or if you are alone, running off and leaving you. Locator beacons are for summoning help from a distance (GPS-type) or helping your crew find you (AIS-type) and are not going to solve the more immediate problems the new USCG regulation is targeting. Perhaps we will soon see product combining both of these features, but not yet.

Rescue Mode. All of the wireless devices have a means of restarting the engine so that you can pick up the MOB. Traditional tethers only allow this if you keep a spare lanyard at hand. The temptation, of course, is to plug in the spare and skip the helmsman’s lanyard altogether.

Multiple devices. All of the units have a means of designating either a single or multiple helmsman and a number of passengers. The units will stop the engine when a helmsman sensor triggers, or sound an alarm (without stopping the engine) if a passenger sensor triggers.

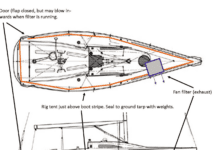

Installation. Wiring is generally simple. A pair of wires are connected either in place of (MOB+) or in series with the existing kill switch (Virtual Lifeline). A positive and a negative wire supply power to the hub. The Autotether requires no wiring; simply mount it within a foot of the existing kill switch. It is the only unit that attaches easily to dinghy motors, since it requires neither wiring or a 12 volt power supply.

Autotether

The only no-installation version. Instead of wiring into the engine circuits, it features a lanyard clip that unplugs itself from the existing kill switch when triggered. A small plunger simply pushes the clip out from under the stitch flange. The hub runs off an internal battery and must be mounted within 12 inches of the kill switch using Velcro pads. LEDs signal when the unit is active, and a buzzer supplements the engine stop function. It’s not very loud, but if the engine stops suddenly and all goes quiet, it seemed like enough.

Bottom line: This is our Best Choice for small outboards without console controls.

Emergency Cut-off Switches

| MANUFACTURER | FELL MARINE | MOB+ | PROPELLOR GUARD TECHNOLOGIES |

|---|---|---|---|

| MODEL | Autotether | MOB+ | Virtual Lifeline |

| ADDITIONAL SENSORS | 3 | 4 | No limit |

| TRIGGER Proximity Proximity Immersion | Proximity | Proximity | Immersion |

| PRICE ( BASE AND ONE FOB) | 235 | 179 | 360 |

| ADDITIONAL FOBS | 95 | 60 | 79 |

Virtual Lifeline

Propeller Guard elected to go with conductivity-based detection after testing of a proximity-based system proved unreliable. If the radio signal was strong enough to avoid false alarms it could fail to function quickly enough. Instead, they Virtual Tether uses a pair of electrodes that are well-shielded from splashes and rain. It has proven durable and reliable enough to satisfy a following of law enforcement agencies in a number of states. Available in both surface mount and below deck versions.

Bottom line: Recommended by virtue of its track record.

MOB+

Fell Marine solved the proximity/water immersion/false alarm puzzle by developing a signal protocol they call Wimea. Like all of the systems, it alarms and cuts off the motor if the sensor is taken 50-150 feet from the boat. It also alarms if the sensor is submerged 4-6 inches.

Up to four additional fobs can be paired with the hub, creating alarms for

passengers and engine stop for the primary operator. The idea, of course, is that this give the operator better control of the situation. The boat doesn’t need to stop instantly to avoid the “circle of death” if the operator is still at the helm, and if operators change, they can exchange fobs. If the operator position is more fluid, changing frequently, this could compromise safety.

Bottom line: This is our Best Choice for a small fishing boat.

Conclusions

We’re staying with a cable kill switch for our dinghies. It’s a slight nuisance, but we like the simplicity. For small fishing boats we like the mobility of wireless systems and the seamless ability to trade off helmsman duties. It is all too easy to forget to clip in when moving between fishing spots. As for sailboats, it’s not required, but this is one more MOB safety item worthy of consideration.

AUTOTETHER, www.autotether.com

PROPGUARDTECH, www.propguardtech.com

MOB+, www.fellmarine.com