In several of the most recent reports on anchor testing, Practical Sailor has commented favorably on the setting ability and holding power of the relatively new anchor called the Bulwagga. Overall, it was outranked only by the Spade.

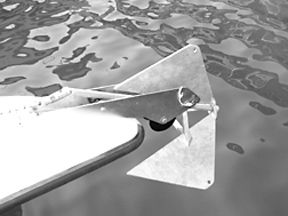

However, we did dub it “strange” and “difficult to stow.” That’s because it’s a triangular anchor that doesn’t fold, won’t lie flat, and seems to have a lot of pointed corners. A suitable mounting system would make it much more attractive.

Perhaps of interest to those who may be considering the Bulwagga (but might be put off by its awkwardness) is a note received from another reader, Rob Hoffman, a multihull sailor with whom Practical Sailor has corresponded on the subject of LED light bulbs.

Hoffman bought a 27-pound Bulwagga for his cruising multihull and carries it in a slightly modified Bruce bow roller fitting. (The United Kingdom anchor manufacturer Bruce makes several sizes of bow rollers; the one Hoffman uses is a Model BRM-4, made for a 22-pound Bruce; it discounts for about $200.)

He said he was prepared for some difficulty figuring out how to carry the Bulwagga. He was pleasantly surprised when he found that he needed only to remove the top roller of the Bruce and drill a hole in one fluke of the Bulwagga to accept the stock-locking pin used with the Bruce.

Hoffman said he continues to “really like the Bulwagga” and, “The Bruce mount works and looks well with this ‘difficult’ anchor.”

His marriage of Bulwagga anchor and Bruce mount is a good fit.

Use the accompanying photo to decide whether you can consider it a thing of beauty, a subject on which there will be no voting, no Practical Sailor tabulation, no recounting, no search for pregnant dimples, no hanging chads, no letters to the editor.

—DN

The Seagull and the Vincent

When I was first learning to cruise sailboats with cabins I counted much on my old Michigan friend Bob Linday.

Bob smoked a pipe and wore a Greek sailor’s hat. He was good in the shop, being a fairly precise sort of fellow who appreciated quality work. He had ordered his English twin-keel 17-foot Silhouette Mk II directly from the Motherland. Mousle was too small to hog up with a lot of gear, so every addition had to be carefully considered over the long winter months.

For his auxiliary, there was no choice for Bob other than the venerable British Seagull outboard. It was, he said, a marvel of simplicity and trusty English engineering, the sort that enabled the Brits to prevail over the Germans during World War II. He loved to tell the story of a man whose Seagull ran out of gasoline in the middle of the ocean. Desperate, he poured parrafin into the tank. As the engine was weaned and converted to the new fuel, it coughed once or twice, then knuckled under and continued to purr.

So savagely was I indoctrinated with the Seagull’s virtue that when it came time for me to buy my first outboard, it could be no other.

My view of the motor soon changed, however. The brutish assemblage of loosely fit parts was loud and smelly. And it was slow. I tried to love the thing, but was having increasing difficulty until one day I was motoring along towing a dinghy. I planned to run the bow of our Catalina 22 up on a protected beach. Because the Seagull had no transmission, I cut the engine and coasted in. The bow cut into the sand and stopped. I turned just in time to observe the dinghy come gliding up from behind and its bow neatly bust off the Seagull’s exposed spark plug. During the ensuing tow back to the marina, I vowed to buy a new, American outboard.

The Johnson 6-hp. outboard pushed the boat much faster, was far quieter, and had a forward-neutral-reverse transmission. Once I realized I had neither committed a sin nor required therapy for going against Bob, I wondered why I had ever been taken by the wretched Seagull.

But did I learn my lesson? No.

A few years later, having sold the Catalina and still under the Anglophile’s influence, I bought a wooden Silhouette with an inboard air-cooled Vincent motorcycle engine under the cockpit floorboards. It made the most horrendous racket imaginable, but it was an inboard! It lasted one season before seizing.

I wouldn’t give a farthing (or a quarter) for the two of ’em.

—DS