Testers put six rope clutches through their paces on a test jig that measured line tension, line slippage, and the clutches holding ability over a long period of time. In terms of overall value and performance, the units tested were a tightly grouped field of competitors. Practical Sailor testers evaluated rope clutches from Euromarine Trading (Antal), the Antal V-cam 814 and Antal V-grip Plus; Lewmar D-1 and Lewmar D-2; Spinlock XCS and Spinlock XTS; and a prototype clutch from California-based Garhauer Marine Hardware. The search for the best rope clutch took a look at the pros and cons of employing a rope clutch for specific tasks as knowing when to clutch and when not to clutch is imperative for efficient line handling and safety.

****

Photos by Ralph Naranjo

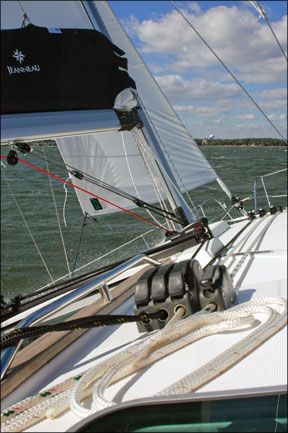

Rope clutches have redefined “string theory” on sailboats, and the result has been a growing trend toward fewer winches, more side-by-side line leads, and lots of extra rope in the cockpit.

This “all-roads-lead-to-Rome” approach to running rigging is so compelling that it is dictating cockpit layouts and the way running rigging is arranged on modern sailboats. With sheets, guys, halyards, reef lines, topping lifts, and more winding their way to the cockpit, builders and designers are relying on the ubiquitous rope clutch to make line handling more manageable.

Just over a decade ago, halyards, sheets, and even reefing lines often had their own winches. Some lines were handled at the mast, others further aft. Now, a single winch is expected to serve multiple tasks, and the rope clutch makes this possible. This handy device lets us tension a line and then lock it in place with just the throw of a lever. Once clamped in a clutch, the line can be removed from the winch so that another line can be tensioned and clutched.

At first glance, this arrangement seems like a great boon for sailors: Not only do we save money on winches, we can have the convenience of handling all our control lines from the cockpit. But our growing reliance on rope clutches also has a downside that deserves closer scrutiny.

With a focus on real-world application of rope clutches at sea, Practical Sailorrecently undertook an in-depth look at rope clutch technology. In our last test (“Clutch Play,” April 2006), Lewmars versatile, yet rugged D-1 rope clutches climbed to the top of the heap. For this go-round, weve slightly modified the closely controlled test procedures (see, “Comparing Slip and Line Chafe”) to judge how clutches might behave in the less-than-ideal circumstances we encounter at sea.

Looking At The Loads

Whether it is associated with sheets, halyards, runners, lifts, or reefing lines, the working load on a line can vary from benign to extreme. So when considering the choice of a rope clutch, a clear understanding of the load range is key. Just as significant is how often and how quickly the load will need to be adjusted. The bottom line hasn’t changed: When it comes to handling a line under heavy load, youre always better off with wraps on a winch drum.

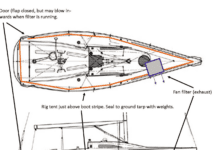

Transitioning from a locked clutch to a loaded winch should be as simple as possible. Placing the operator in an ergonomic position with a view of the sails and room for easy winch grinding is vital. These considerations lead to our second lesson learned, a reminder about deck layout and line leads.

Even the best rope clutches can’t cure poor layout choices, such as leading too many lines to a location that is impossible to work in. The last thing you want to be doing when a midnight squall descends is juggling six lines led to a single winch under a cockpit dodger that obstructs all view of the sails. Throw a nearby chartplotter into the picture (see photos, page 13), and watch as your four-color view of Bermuda is gift-wrapped in double-braided bow ties.

Potentially far more costly is the setup seen aboard many multihulls that use a single undersized winch to control both a genoa and a main sheet, requiring one or the other to be locked off in the jaws of a clutch. In our midnight squall scenario, the load on the sheets can quickly triple with the first puff. Just when easing one or both sheets quickly becomes critical, youre faced with a complicated arrangement that dashes all hopes for a quick response.

Early rope clutches required a line to be set on a winch and tensioned prior to releasing the clutch. The latest rendition of line handlers provides a release-under-load capability-a feature with both significant advantages and disadvantages. In the plus column is the clutches ability to efficiently organize lines according to tasks and run them sensibly to key cockpit and/or mast locations. Two or three reef lines in a slab-reefing system can be handled with rope clutches and one winch, so can halyards that are set and left in a fixed manner for long periods of time. But locking down a line under 1,000 pounds or more of tension, and then releasing it without having it controlled on a winch drum is truly like catching a tiger by the tail.

What We Tested

For this comparison, we selected six clutches from four manufacturers. Antal, an Italian company known for developing handsome hardware, sent us two units. Lewmar, a favorite in our last comparison, sent us its popular D-1 and D-2 clutches. Spinlock, a UK company long known for its clutches, sent us three of its latest designs. We also tested a prototype design from California-based Garhauer that has since been significantly redesigned.

Antal

The two Antal clutches we tested incorporated a radiused V-shaped investment-cast stainless-steel jaw that rotated into place, clamping the line. The smaller sized V-cam 814 locked with the holding power of a pelagic shark but could be released under full load with only a light pull on its short cam-lock handle. However, the geometry of the release device caused the handle to flip forward with considerable momentum. Testers learned to pull their hands away quickly to avoid getting smacked. (Antal said no users have complained about this.) Slippage was minimal, although a close inspection after the abrasion test revealed a higher than average amount of fiber rupture. Antal says its newer versions have been modified to reduce friction as an unloaded line is pulled through a closed clutch. Overall, the V-cam 814s workmanship and low slippage outweigh its shortcomings.

Antals V-grip Plus is a beefy clutch with solid alloy sides, and its internal workings are easily accessed with a large Phillips screwdriver. A big advantage of this clutch is its rugged structure and the ease with which it can be serviced. The stainless-steel jaw should hold up better than the aluminum gripping components in other units.

Bottom line: Rugged construction and ease of maintenance make the Antal V-grip Plus a sensible choice for long-distance cruisers. The V-cam 814 offers outstanding grip for your dollar, but has a quick release function that will test a sailors reaction time.

Garhauer

When Practical Sailor initiated this test, Garhauer had just released a rope clutch that featured some innovative features, including an extendable lever arm that reduces the effort required to release the cam under load. While Practical Sailor was rounding up other new clutches to compare, the Garhauer clutch-unbeknownst to the Practical Sailor testers involved-was being improved.

As it turns out, the clutch Practical Sailor tested for this article was effectively a prototype, with obvious shortcomings that the newest version has apparently fixed. The issues included exposed gear teeth at the top of the clutch, and below-average holding power. Under its unconditional 10-year warranty program, Garhauer is offering to replace or fix any early versions-owner Bill Felgenhauer estimates there are only “a dozen or so out there”-with the new one. The original clutches are recognizable by their solid sides. (See photo, page 10.) The newest version has inspection slots cut into the sides.

Bottom line: Owners of the “beta” clutch will want to switch to the new one.

Lewmar

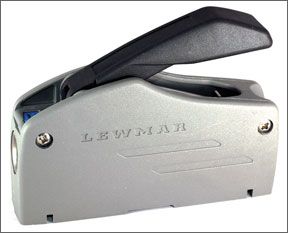

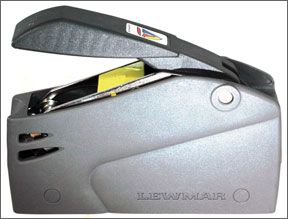

Both the D-1 rope clutch and its big brother, the D-2, are well-engineered investment-cast stainless-steel structures housed in reinforced plastic housings. Their levers close in the direction of the load, and their locking function is unique. The line passes through holes in a series of vertical domino-like rectangles also made of investment-cast stainless steel. When can’ted away from a vertical alignment, the relative diameter decreases and the line locks with only a small amount of initial slippage. Even with the units relatively short lever arm, the load is easily released. After minimal initial slippage, the long-term load holding was excellent.

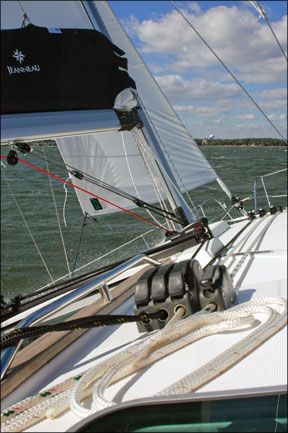

Lewmars clutches are small and light and offer an ergonomic appeal. There are no protrusions that can hook lines or get in the way, and racers looking for light weight and lots of holding power wont be disappointed.

Testers did notice a number of broken filaments and fuzz on the line cover after only 25 cycles. Rope abrasion is a concern with all clutches, and in a future Practical Sailor test we will look at differing line types to determine which are least susceptible to such abrasion.

Bottom line: Well-designed and moderately priced, the versatile D-series has rightly earned a place on a wide range of sailboats.

Spinlock

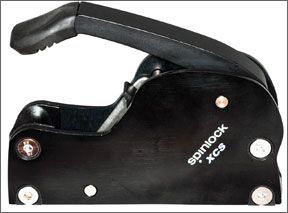

The XTS and XCS both utilize the same 0814 cam system. The only difference is that the XCS has an aluminum frame, and the XTS is high-strength plastic. When used on a mast, or where a clutch can be hit by a pole-end or other high point-force, the metal XCS makes better sense. Both models were easy to thread, allowed a butter-smooth pull (even when in latch-down mode), and featured a comfortable, ergonomic handle design. During testing, only 22 pounds of pull was required to release the clutch under load.

Spinlocks jaws clamped down vigorously on the line, held with minimal initial slippage, and had enough surface area to spread the load, helping to minimize cover abrasion. The inner workings were easy to access, and a close look at the design of the gripping components revealed lots of surface area for good line contact.

The heavy-duty XX0812 stopper excelled as a high-load line-handler but was more difficult to thread. Testers actually had to unscrew the end cap to thread the 7/16-inch line through the clutch. Compared to the other clutches, more effort was required to pull an unloaded line through the XX0812, but its ability to hold loads without allowing slippage topped the scale. The XX dwarfed all but the Antal V-grip Plus.

Bottom line: The well-designed XTS and XCS clutches excelled in all tests. A high-load champ, the XX0812 is better suited to highly tensioned lines aboard boats in the 50- to 60-foot range.

Considerations

The disadvantages of rope clutches can outweigh the advantages when you overdo it. However, after sailing aboard a wide range of clutch-equipped new boats and bench testing the latest trend in line-handling hardware, Practical Sailor stands by its view that rope clutches are indeed a worthy innovation. Those shopping for a sailboat or pondering a running-rigging upgrade should get to know both the pluses and minuses of the latest clutch technology and the tradeoffs that are part of the deal. For example, its easy to ignore the almost maintenance-free nature of a conventional cleat, and the utter simplicity and safety of handling a sheet wound about a good-sized winch thats dedicated to a single line. So, before you jump into a clutch-centric makeover, give some thought to whats to be gained and what will be lost.

Rope clutches are like trumpets in an orchestra, a bold and powerful presence, but one that can easily be overdone. When pondering their use, never lose sight of the “0300 Rule”: The worst things that happen on offshore races or cruises tend to occur in the middle of the night, when sail handling is more like a Braille exercise than it is a visual experience. Fiddling with fussy, coiled lines in cute little pouches or confronting six or seven lines led to one winch is by no means a step forward when it comes to line handling. Faced with an emergency, experienced sailors would much rather have a line pre-wrapped on a winch drum than locked in a clutch. In fact, sailors with “over-clutched” sailboats need the dexterity of a Las Vegas card dealer to cope with the demands of switching lines on a winch, re-tensioning, flipping levers, and coping with a couple hundred feet of extra line strewn about the cockpit. In light to moderate breeze during the day, this string fiesta is less daunting. Add some heel and increase the tension in the running rigging, and the winch deficit will become painfully evident.

By no means is Practical Sailor against rope-clutches, but they need to be applied with prudence. Its not simply a question of how many clutch-locked lines should be led to a winch. You also need to think about the loads that are associated with those lines. Consider for example, the difference between a halyard, a preventer, a running backstay tail, a jib sheet, or an after guy. At times, many of these lines hold modest amounts of potential energy that can be safely managed by a bare hand. But add some breeze or an unanticipated jibe or broach into the equation and watch out. While it is nice to know that in an emergency a modern rope clutch can be released under 1,000 pounds or more of load, it is also frightening. Picture a person holding a preventer line in one hand and blowing the clutch with the other so that a backwinded mainsail can flop over and help the boat recover from a broach. The load on the single-purchase preventer is now equal to what the multi-purchase mainsheet held before the broach. In this scenario, no winch drum lies between the line holder and the load. In short, if you decide to flip the clutch lever unaided by a winch, beware of the kinetic energy youre about to release.

In many cases, the cabin-top winch that once held the main halyard load is secured with six bolts arrayed in a circular pattern, and the rope clutch about to replace it has only two in-line bolts dedicated to handle the same load.

Although the bolts for the rope clutch are engineered to handle the devices load limits, in many cases, the cored coach-roof where the clutch is mounted is not. New boat designers engineer solid, fiberglass-reinforced-plastic (FRP) “in fills” in such highly stressed areas, and anyone planning to refit an older boat with rope clutches should consider this approach. Bonding FRP top-plates and backing plates to the area will help spread the load, but care must be taken to seal the core in the area so water intrusion does not become an issue.

Photos by Ralph Naranjo

0)]

And because some rope clutch spare parts are hard to find, a spare clutch is recommended for cruising boats.

Conclusion

We found the units we tested to be a tightly grouped field of competitors. In terms of overall value and performance, we ranked Spinlocks XCS as the Best Choice and gave the Lewmars D-2 the Budget Buy. It is interesting to note that boatbuilders have come to the same conclusion, at least if the tally at fall boat shows is any indication. A quick look at the fleet revealed that the Spinlocks XTS (another good choice) and XCS units were the most prevalent clutch, and builders seems pleased with their performance.

Selecting the right clutch is important, but as much or more emphasis should be placed on how you intend to use the clutch. Rope clutches for halyards and reefing lines certainly make a lot of sense. Topping lifts and down guys, asymmetric spinnaker tacks, and a host of other line controls also benefit from such technology. Using a clutch for a main or genoa sheet may save on winch cost, but this can be shortsighted thrift. Lines under significant load, and ones that must often be trimmed, deserve their own winch for efficiency as well as for safetys sake.