Photo courtesy of Norseboats

288

In 2005, Practical Sailor had the chance to sail a 17-foot, modernized version of a New Jersey beach skiff, a small, beach-launched fishing boat/rescue boat that once crowded the Jersey beaches in the mid-1800s. The Norseboat 17.5 earned a healthy endorsement from Practical Sailor, garnering mention in our 2005 “Gear of the Year” issue—something typically reserved for gear only.

Since then, the Norseboat 17.5 has earned a loyal following among small-boat fans, and the builder has introduced a new, larger version with a cabin, the Norseboat 21.5. Like its predecessor, the 21.5 is designed for the small-boat adventurer who likes to travel with as few mechanical encumbrances as possible. Its light weight (less than 1,800 pounds with trailer) makes it easy to tow with a mid-size car, and its shallow draft (less than 18 inches) opens up remote coastal cruising areas that bigger boats can’t reach.

For those who like to explore by backpack, bicycle, kayak, or canoe, the boat is a logical upgrade, broadening the horizons while adding a little more comfort. For a clearer picture of what the Norseboat concept is about, see the report on the 2010 Arctic Mariner Expedition (www.arcticmariner.com), which documents the adventures of two British Royal Marines who tackled the Northwest Passage in a Norseboat in 2010.

Design and Construction

Like the 17.5, the 21.5 was designed by Mark Fitzgerald, the former righthand man to yacht designer Chuck Paine. Now retired, Paine is best known for the elegant, dependable sailboats he drew for Morris Yachts, beginning with the 26-foot Frances. Aiming for the smallest, lightest boat that could be called—with a bit of a stretch—a “pocket cruiser,” Fitzgerald took the Norseboat 17.5 as a starting point, stretched it out, and added more form stability and lead ballast in a stub keel where the centerboard is housed.

The hull is the hull is solid FRP lapstrake above the waterline, smooth cored FRP below waterline. The core and FRP lapstrake shape adds rigidity to a relatively thin layup schedule that helps to keep weight down. The hand-laid fiberglass consists of two layers of 1808 double-bias biaxial cloth (+/- 45-degree), with critical areas receiving additional layers of glass. Below the waterline, there is a smooth underbody (no lapstrakes) reinforced with a 3/8-inch foam core. Vinylester resin is used in the outer layers to resist hull blistering, and polyester is used in the interior layers.

The balance of the boat structure is a composite of meranti plywood, epoxy, and glass cloth. The deck and cabin roof beams are laminated wood-and-epoxy composite, giving the interior cabin surface a very smooth finish. The deck is screwed and bonded into a wood sheer clamp that is bonded to the hull. All of the structural wood is encapsulated in epoxy resin and/or cloth, keeping the threat of rot and termites at bay.

The foil-shaped stub keel is 9 inches deep with the centerboard trunk inside. There is a lead/epoxy core between the keel exterior and the centerboard trunk, adding 250 pounds of ballast. The four-foot-long centerboard is the same as that on the 17.5, weighted with about 50 pounds to assist in lowering.

Beam is just over seven foot, and the bow is finer than the plan view suggests. When compared to the Norseboat 17.5, the new hull’s additional wetted surface of the stub keel is the clearest performance trade-off.

The carbon-fiber mast weights only 19 pounds, is 19.5 feet long and is supported with pre-stretched Spectra. The mast pivots easily in its stainless-steel step.

On Deck

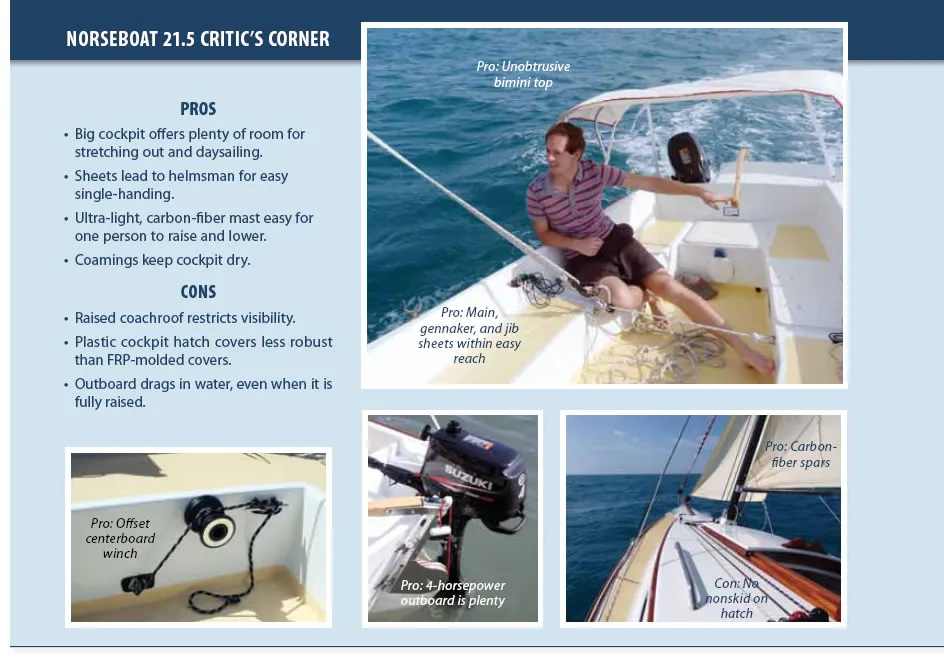

Anytime a designer ponders the shape and dimensions of a cabin on such a small boat, he is forced to make compromises. If functionality were the only consideration, the decision tree would have only a couple of branches:

1. How important are comfort features such as headroom?

2. How important are seagoing features such as wide sidedecks, low windage, and a clear view from the helm?

If you favor one, then you generally compromise the other.

On a boat where traditional aesthetics are valued so highly, however, a third factor looms: What’s going to happen to our quaint little beach skiff when we give it a top hat?

288

We can imagine Norseboat President Kevin Jeffrey and Fitzgerald had many long discussions regarding the proper cabin height on the Norseboat 21.5. Jeffrey emphasizes the boat’s sitting headroom to customers, while Fitzgerald’s commitment to eye-appeal and proportion is well known. In our view, the deck could go a bit lower, even at the expense of headroom. For the purist, Jeffrey offers an “open” design with only a tiny cuddy.

The cockpit is 8 feet, 6 inches long with a high bridgedeck and encircling coamings. For longer cruising, you could fit light plywood panels over the 6-foot-long footwell and enjoy a pleasant double berth under the stars or beneath the camping tent option.

During our test sail we had three adults and three children aboard, and there was a comfortable place for everyone to sit in the cockpit.

Instead of the usual hinged, molded lids, the three cockpit lockers have plastic, aftermarket deck hatches. So long as their gaskets are in good order and kept clean, these hatches are watertight. We’d prefer more rugged fiberglass molded lids with gaskets and stainless hardware, but that is more expensive and time consuming for the builder.

The sheeting arrangements were convenient to handle from the cockpit. The 4:1-ratio mainsheet rides on a rope traveller that traverses the cockpit well. This allows for more flexibility (and fewer bruised shins) than an aluminum traveler, and is easy to reposition out of the cockpit when the boat is at anchor. Our test boat had the optional wood-laminate sprit with a furling gennaker. On either side of the cockpit are two recesses for a pair of cam cleats. The starboard pair take the furling line for the working jib and the starboard gennaker sheet. The port pair accepts the gennaker furler and the port sheet.

All halyards lead to Harken cam cleats on either side of the companionway. The sheets for the working jib also lead to cam cleats near the companionway, but a singlehander can still flick them in and out of the cam cleat without leaving the tiller. Optional canvas sheet pockets on the bulkhead collect the lines. A small winch at the front of the footwell raises and lowers the 4-foot-long centerboard. The sidedecks are at the lower limits of being wide enough for safe passage fore and aft, but handrails on the cabintop add security. The boat we sailed did not have stanchions or lifelines, and if installed, they would likely inhibit passage fore and aft—a typical tradeoff in boats this size.

288

The foredeck is dominated by a large ventilating deck hatch, large enough to also serve as an escape hatch. Forward of this hatch is a small anchor locker, also accessible from inside the cabin. Two 8-inch Herreshoff cleats on the bow are more than adequate for handling anchor and mooring duties. The bow chocks are relatively small and put a sharp bend in the rode, making proper chafe gear essential.

The bobstay for the sprit will likely chafe on the anchor rode or snubber as the boat veers at anchor, so you’ll need to protect against chafe there as well.

Accommodations

Down below, the Norseboat 21.5 has some neat features that make it a relatively comfortable camper-cruiser, suitable for short overnighters or longer gunkholing expeditions, depending on where your comfort threshold lies. The rated maximum load, including persons, outboard, and all supplies and equipment, is about 2,400 pounds.

A convenient slide-out sink and alcohol stove are tucked just under the companionway to serve as the galley. The spot allows for plenty of ventilation during meal preparation. Just to starboard of the stove is a slide-out port-a-potty. This could be relocated forward for those who don’t like the idea of cooking in such proximity to a port-a-potty. Both of these slide-out amenities required fiddling with small locking pins to lock them in place.

The removable compression post allows for a mini romper room for kids or plenty of sleeping area for adults. If family overnight trips is what you had in mind, the optional cockpit tent would add privacy, and four people could sleep below in a pinch. In terms of creature comforts, we can imagine few complaints from anyone who subscribes to a Thoreauvian approach to cruising.

Performance

Like its predecessors, the Norseboat 21.5 has a short, curved gaff, which makes the boat easily recognizable. The design precludes the use of a fixed backstay; the Norseboat relies instead on shrouds angled well aft for support off the wind.

It is a reassuring boat, relatively dry, and responsive, but its overall sailing ability was not what we would call high-performance by contemporary measures. Conditions for our test sail were about 8 knots of wind with a light chop.

Pointing ability and tacking speed were average, but the boat was well balanced and exciting on a reach with the sheets eased. Jeffrey said that the boat we sailed was fitted with an incorrectly sized rudder that was 7 inches too short. A longer rudder should improve performance, particularly on the wind.

Sailing to windward in smooth waters with the working sails, the boat averaged around 47 to 53 degrees true to the wind. Speed over ground was 4.5 to 5 knots. While reaching with the working jib and mainsail at true wind angles of 75 to 90 degrees, speeds averaged between 5.6 to 6.2 knots. Under the gennaker and a mizzen staysail, reaching with the true wind between 120 and 130 degrees, the boat averaged about 5.7 knots. Running the 4 horsepower, four-stroke Suzuki outboard at about 80 percent throttle gave an average speed of 5 knots.

The boat maneuvered well under power, but the shift lever on the Suzuki is back on the starboard side of the engine, requiring the helmsman to reach back awkwardly across the motor-well to shift. Ideally, any shifting during docking maneuvers is carried out before you wrap the nearly $2,000 sprit, furler and headsail around a piling.

Although the boat has rowing stations, oars would serve only to get the boat in and out of a slip or to a mooring in calm conditions, when sailing was not possible. Those considering electric propulsion should also look at a Torqeedo electric outboard (www.torqeedo.com).

Conclusion

From a practical standpoint, a less expensive trailer-sailer can accomplish all that the Norseboat 21.5 does. You don’t need a $35,000 Norseboat to poke around the Gulf Coast islands, the Lakes region of Minnesota, or the Florida Keys, or the sounds of North Carolina, or any of the many outstanding small-boat cruising areas North America is blessed with. Some sailors might be happier to have a renovated 38-year-old Venture 21, like the one we reviewed in the April 2011 issue, and put the $30,000 they’d save toward the next adventure.

However, several important features—a contemporary, sea-kindly underbody, high-quality construction, good fit and finish, and a sensible centerboard arrangement—put the Norseboat head and shoulders above vintage trailer-sailers.

After including an easily stepped, 19-pound, carbon-fiber mast, the convertible interior space, and ample cockpit stowage, the scale begins tipping more toward the Norseboat. And of course, you’ve got a new boat, not a 38-year-old hull. Even when you start looking at new boats, there are very few that have the same visual appeal as the Norseboat.

Anyone investing in the Norseboat 21.5 should recognize that much of the boat’s value is in its charm. Those who like the idea of a solid, easy-to-sail boat with a clear link to New England’s maritime tradition will immediately fall under its spell. Those who measure value in dollars-per-foot probably won’t. The price tag seems steep for a 21-foot trailer-sailer, but given the success of its Norseboat 17.5, the maker is clearly on to something.