Among the 40-plus pieces of equipment tested at the symposium were electronic devices designed to alert the crew of a man overboard and help locate him in the water.

In Practical Sailors view, before any investment is made in these devices, sailors should take a good look at the systems designed to keep crew on board in the first place -lifelines, jacklines, harnesses, tethers, nonskid decks, grab rails etc. Likewise, the crew should be well-versed in man-overboard (MOB) procedures. It has been said that these units are $1,000 solutions to a $100 problem, and in some respects, they are.

In recent years, however, a few prominent, fatal man-overboard incidents have caused the sailing community to revisit the gear and techniques used for alerting and recovery. One factor several of these incidents had in common was the inability of the crew to execute the recommended Quickstop maneuver in time to keep the victim in sight. In some incidents, boatspeed and windy conditions caused the rapid separation of the vessel and the victim.

Sailboats, even cruising boats, are faster than ever. Add to this the fact that the off-the-wind Quickstop maneuver (spinnaker up) is much more difficult to execute, and it becomes clear why boatspeed and victim/vessel separation are such a growing concern. The shorthanded cruising couple or delivery crew isn’t immune to MOB concerns. For these sailors, solo watchkeeping presents significant obstacles to a timely response and recovery.

In the face of these challenges, technical experts have been continually refining a new breed of equipment that has reshaped the way sailors approach a man-overboard situation. The devices include personal beacons, alarms, trackers, and other gadgets aimed at expediting alert and recovery. Some products signal that a person is no longer on board the boat. Other devices broadcast a radio (RF) signal that can be located with on-board direction-finding (DF) equipment. Theres even a new type of mini-406-MHz EPIRBs called Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) that can summon the U.S. Coast Guard via satellite. Add to this a recently introduced satellite messenger system that can pinpoint the position of its owner, and the choices become more than a little confusing.

We evaluated seven of these devices: the ACR ResQFix, two Mobilarm MOBi-lert systems, the Raymarine LifeTag, Emerald Marines Alert2, Marine Rescues Sea Marshall, and the Spot messaging device.

OB Alarms

The primary purpose of these small, lightweight, clip-on gadgets is to keep track of individual crewmembers when they are on deck. An RF reference signal keeps the alarm shut off. If the signal stops, an alarm sounds, announcing that a beacon wearer is either in the water or beyond the range of reception of the signal.

These devices do not broadcast a direction-finding signal, but the node can be linked to a digital charting system/GPS network to indicate where the crew went over the side. This arrangement effectively works as if someone has punched the MOB button on a GPS or chartplotter. It doesn’t track the victim in the water, but can help guide you back to where the alert was first activated.

In the MOB alarm-only category, we tested the Mobilarm MOBi-lert and the Raymarine LifeTag systems.

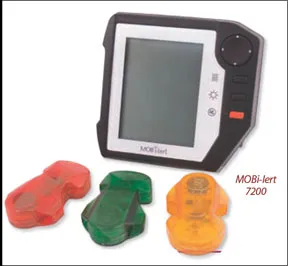

Mobilarm MOBI-LERT

We tested two products in the Mobilarm MOBi-lert line: the less expensive 720i, which features a basic LED alerting display, and the 7200, with a more sophisticated LCD display screen. A third product, the top-of-the-line 7600, is nearly identical to 7200, but features an integral GPS receiver. The MOBi-lert systems trigger an audible alarm when the RF signal between the wearable beacon and the base station is interrupted, typically because the beacon is in the water or out of range. It has a relay component that can actuate an MOB waypoint and-in the case of the 7200 or 7600-plot it on a dedicated LCD screen. All of the units can interface with National Marine Electronics Association (NMEA) 0183-compatible devices, so that MOB waypoints can be plotted on a GPS or chartplotter. All models have a relay-switching capability that can turn various devices on. It can even activate a 406 EPIRB.

The Australian-designed alarm system has a couple of features not found in the Raymarine LifeTag gear, and this helped the MOBi-lert stand above the LifeTag system, in our opinion. One interesting difference between the systems is MOBi-lerts use of a remote mini-dipole antenna that helps cure false alarm problems without resorting to a time delay.

Another noteworthy detail is the inductive charging system, which requires no metal contacts between the charger and the beacons, allowing the beacons to be better sealed from water intrusion. All the pendants registered are monitored all the time. The status of each is always visible either by LEDs as in the 720i or on the screen for the 7000 series, which gives battery level and signal strength.

Other interesting features include: A low battery is indicated at both the pendant and the console; there are various wearability options to ensure the pendant is submerged if someone falls overboard; the alarm system signals when the vessel moves more than 100 meters from the MOB position and (using a different sound) when it comes within 50 meters (so the boat doesn’t run over the unfortunate person in the water); and the unit logs all events.

Bottom Line: The MOBi-lert system wont bring a vessel back to a victim who has drifted far from the point he went overboard, but smart design and consistent performance make this a Practical Sailor Recommended product in this category.

Raymarine Lifetag

This small alarm is a handy little strap-on device that weighs only 2.2 ounces and provides a battery-check feature along with the ability to switch the unit on and off. It links to a controller, and while a crew remains aboard, the “black box” automatically polls each LifeTag that is activated. According to the instructions, when a “tag” gets wet or moves beyond the receivers range (about 32 feet), the unit squawks a loud warning. If the controller is wired to Raymarines Seatalk Network, it can also trigger the chartplotters MOB function, automatically charting the victims location at the time of the incident.

According to Raymarine, the alarm should sound within 10 seconds of a victims going overboard. In all four of our test runs, the time elapsed from the moment the subject hit the water to the time the alarm sounded was much greater than 10 seconds-over 42 seconds in one instance. Testers also noted inaccurate fixes for the initial MOB location. During the 5-knot test, about 100 yards separated the point where the victim hit the water and the displayed MOB point. At 20 knots, simulating a race boat reaching, the MOB mark on the Raymarine E-120 screen was approximately a quarter-mile from where the victim actually hit the water. The discrepancy of the positions had nothing to do with current or strong breeze, which in a real-world situation, could further influence the location of a person in the water.

Bottom Line: Upon reviewing Practical Sailor findings, Raymarine technicians commented that the testers results did not conform with the LifeTags operating specifications. Raymarine experts plan to inspect the tested units to determine why the product did not operate within its designed specifications. Practical Sailor will report on any further news regarding this LifeTag system.

Beacons

Just as the U.S. Coast Guard uses direction-finding equipment to home in on the 121.5-MHz secondary signal of a 406-MHz PLB or EPIRB, a crew with DF equipment can home in on a beacon signal. Several manufacturers make dedicated beacon and receiver units meant to be used autonomously aboard small boats. Some also provide an MOB indicating alarm and offer relay controls that can shut an engine off, cause an MOB position to be recorded, and even switch a relay that disengages an autopilot.

The two alarm-plus-DF devices we reviewed are the Emerald Marine Alert2 and Marine Rescue Technologys Sea Marshall SARfinder 1003.

Alert2

Comprising an alert beacon, base station, and a handheld DF antenna, the Alert2 system from Emerald Marine Products is a good example of what we consider an autonomous device. It is both an alarm and a beacon designed to be located by a DF device. The device is designed to alert and actively assist crew in locating an overboard victim. In this case, the water-activated, battery-powered transmitter is worn by each crew on deck. If someone goes over the side, contact with water activates a transmitters 418-MHz signal. The signal is received by an onboard antenna and the receiver, which immediately sets off an alarm and provides switching capabilities for other vital turn-on, turn-off functions.

With the optional PC interface kit, the Alert2 will plot MOB points using a compatible GPS and Nobeltec or Capn charting software. The signal emanating from the beacon can be homed in on using a portable handheld DF antenna (optional) that is straightforward to use, and is capable of detecting the beacon signal up to about 1 mile away.

Bottom Line: The Alert2 functioned as advertised, but the locating capabilities depend upon someone being available to hold the DF antenna while conducting a search.

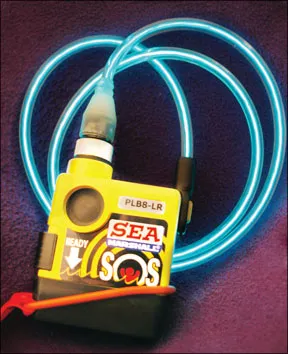

Sea Marshall

Practical Sailor testers evaluated Sea Marshalls top-of-the-line SARfinder 1003 system, which is classified as a Maritime Survivor Locating Device (MSLD). The SARfinder comprises an alert unit (SMRS8-LR), a base unit or receiver (CG121 MKII), and a fixed-mount direction-finding antenna. You can also buy the alert beacons ($295 per beacon) or the receiver ($650) separately.

The alarm is automatically activated by water and transmits the international homing signal (121.5 MHz) back to the base unit on board the boat or to search and rescue (SAR). LED lights arranged in a circle on the base unit show the MOBs position relative to the boats heading. The CrewFix option also allows interface with NMEA 0183 devices to plot the MOB position on a GPS plotter or ships navigation system.

The Sea Marshall system is valued for open-water vessels where time is of the essence for rescue. SAR aircraft and vessels, equipped to search for 406 EPIRBs, personal locator beacons, and MSLDs, carry DF devices tuned to 121.5 MHz to do the final homing process. As mentioned earlier, 406-MHz beacons also broadcast a weak 121.5-MHz secondary signal for this location process. (Direction finding by the U.S. Coast Guard is in the midst of a makeover, see related story this page.) In the case of an MOB rescue in which Coast Guard assets are involved, the value of the Sea Marshalls broadcast frequency goes beyond its use as an “autonomous” DF reference. It also can become a useful reference for U.S. Coast Guard and other SAR agency direction-finding gear.

Bottom Line: Compared with the Alert2, the Sea Marshall has the advantages of 121.5-MHz homing capability and a fixed-mount antenna. It has longer range and also

will interface with various chartplotters via NMEA 0183 interface.

Personal Locator Beacon

Theres good chance that the 406-MHz Personal Locator Beacon (PLB), with its international backing of Rescue Coordination Centers (RCC) and Mission Control Centers (MCC), along with air, sea, and land assets to call upon, will become as important a safety asset as its big brother, the EPIRB. But, because the new technology is basically “just out,” theres not enough real-world marine feedback to make that statement.

One important difference is that theres neither an on-board alarm nor an automatic immersion start function associated with PLBs. The units antenna must be deployed, and a button pushed to initiate operation. Its a simple procedure, but one that requires a conscious victim aware of what to do. The units transmit a 406-MHz signal to geostationary and geosynchronous satellites, and the electronics package in this array of satellites forwards the beacon registration number and position information to the nearest RCC. Prior to launching a rescue mission, the staff at these rescue coordination centers begins the identification and authentication process with a vital phone call. The number they call is listed on the registration form, and their purpose is to ascertain an “at sea” confirmation from a family, close friend, or business associate. Then an MCC is given the situation report, and a rescue mission is put into play. In or near U.S. waters, this may involve a USCG vessel and/or aircraft (H-60, H-65, C-130), and the time to the scene could be hours, perhaps minutes. Even this rapid of a response may be too long, depending upon water temperature and the condition of the victim. And for this reason, a skilled crew and good boat handling remain the first line of defense.

Obviously, PLBs are much more of an effective rescue tool the closer the victim is to well-established search-and-rescue facilities. Away from the developed parts of the world, the rescue mission may be assigned to a nation with very limited SAR capabilities. The beacon will work, but the person in the water will end up on an AMVER alert list, a notification to ships in the region to keep a lookout for the victim and lend assistance if they are in the specific area of the incident.

ACR ResQFix

The ResQFix is ACRs third generation 406 PLB, and it is smaller and more user-friendly than its predecessors. Its waterproof, equipped with a lanyard, and at 10 ounces, it can be comfortably belt worn or carried in a foul-weather jacket pocket. The antenna release and switch can be operated with one hand, and theres enough power in the unit to run a minimum of 24 hours of broadcasting at 20 degrees Celsius.

The PLB carries a built-in GPS, so a victims exact location is encoded in the message. The rescue coordination center can also be “position fixed” via Doppler measurements, and as a SAR aircraft or vessel approaches, its crew can home in on either the 406-MHz or the weaker 121.5-MHz signal.

Bottom Line: The ruggedly built unit is constructed and tested to stringent international beacon standards. Testers did not evaluate the function of this unit for this article, but look for a report on it and other PLBs in a future Practical Sailor issue.

Spot Satellite Messenger

This compact, handheld satellite messenger is the first of a new breed of dual satellite system communicators that offers limited one-way data traffic, a location feature, and an emergency pager function. The waterproof, positively buoyant gadget acquires GPS position info, and allows a user to pick one of several button-activated signaling options. The “check in” button sends an e-mail or instant message to contacts (family, friends, etc.) that have been listed in a data file. The message is essentially an “Im OK” flash. Contacts can be changed during the contract period. Fees increase for a tracker service that repeats this feature in as frequent as 10-minute increments.

The Spot can even play a helpful role in emergencies. With the push of the 911 button, an automated emergency message broadcast transmits the victims current GPS position to a GEOS satellite link that will forward the message to an international emergency rescue center, which relays it to Coast Guard or other appropriate maritime rescue control center. It also tells your regular contacts that an emergency has occurred.

The Spot is not built to 406 PLB standards, will not support the new PLB direction-finding system, and wont count as an EPIRB under International Sailing Federation (ISAF) regulations, but it is a mighty handy and relatively inexpensive extra. It fits nicely into a jacket pocket and can serve double duty as a day-to-day position reporting device.

Bottom Line: While Practical Sailor doesn’t suggest relying solely on this for a search-and-rescue device, it could make a good extra. We will be taking a closer look at its possible onboard-safety role in a future issue.

Conclusion

This is definitely an apples-and-oranges mix, and testers took this into consideration at all times during the evaluation.

In making the final call, PS noted that not all of the gear reviewed was designed to provide an audible alarm, alerting the crew that someone had gone over the side-an important function for many sailors. Some equipment silently sent position information to satellite relays, and on to rescue coordination centers, while other gear functioned as direction-finding beacons with the vessel itself equipped with a DF receiver.

Just as different tools in a toolbox fit different jobs, so do these auxiliary electronic rescue devices. The best choice for a given crew is very dependant upon its size, composition, and most importantly, where the boat will be sailing. For this reason, we felt it misleading to isolate a Best Choice, in this review.

In the case of a coastal passage from say the Chesapeake Bay, Va., to Florida, a 406-MHz PLB is likely to be a crews best choice for rescue. In such a situation, theres usually warmer coastal water and enough survival time for a conventional SAR mission. On the other hand, a crew making a passage from Auckland, New Zealand, to Punta Arenas, Chile, must consider the limited SAR capabilities in that region and the very real threat of hypothermia. In this situation, the direction-finding ability of the Sea Marshall or Alert2 might well be a better tool for a successful self-rescue.

So a key question to ask is which vessel or aircraft is likely to make the rescue, and if self-reliance is the answer, then the value of a loud and immediate alarm and efficient DF capability goes way up. More often than not, a crew who falls over the side is quickly recovered by his or her shipmates. The chance of rescue goes up if the individual has a PFD, whistle, and a strobe, and the crew never loses sight of the MOBs location. The odds improve further if the crew has practiced MOB recovery.

However, there are many situations where a professional agency such as the U.S. Coast Guard or a third party acting as a Good Samaritan, actually accomplishes the rescue. In such cases, knowing the coordinates of the victims location is much better than having coordinates of where the incident first took place.

With this also in mind, we narrowed the field to three recommended choices. For warm-water cruisers in the North American SAR regions, we recommend ACRs ResQFix, which makes good use of the latest Coast Guard SAR assets and is a reasonable price. MOBi-lert was our alarm-only choice, and the DF beacon pick goes to Sea Marshall.

The testers experience on the water in a fairly controlled environment further reiterated one of the most important lessons of this exercise: Technology is no substitute for a seamanlike approach to staying on board. This is and always will be Priority No. 1.