Photo by Fred Bagley

304

Since Apple’s iPad was introduced in April 2010, people have bought 38,500,000 of these touchscreen tablet computers, and of course, many of them are winding up on boats.

Using programs called “applications” or apps, the iPad can do almost anything a laptop computer can do. In addition to the usual tasks that you would do on a computer, there are apps that are particularly suitable for on-board use. But first, a bit about the machine itself.

One of the best things about the iPad is its extended battery life—up to eight hours using most apps (though less if the GPS is being used). The 3.8-volt, 25-watt-hour (6580 mAh) lithium-polymer battery fully recharges with the 12-volt cigarette-plug charger in about four to five hours, faster if you can plug into shore power. The big power user on the iPad is the high-resolution color screen, so if you let the machine go into sleep mode when idle, the battery is easily good for a long day.

The color screen, which doubles as a touch pad, is one of the best aspects of the iPad. With its 9.7-inch (diagonal) LED display and 1,024-by-768-pixel resolution, it has a larger, crisper screen than any of the small-screen chartplotters we recently looked at (PS, November 2011). One shortcoming for on-board use is that the screen is not easily readable in bright sunlight, so you’ll be inclined to move it into the shade or park it under the dodger for good visibility. Another quirk is that the screen has a polarizing layer, so it looks totally black in portrait (vertical) orientation when you’re wearing polarized sunglasses. You have to turn the iPad (or your head) to landscape orientation to see it with polarized sunglasses.

The touchscreen also can get quite oily when your fingers touch it frequently, depending on how greasy you are. Some users just wipe the screen clean on their pants or shirt sleeves, but it is best to carry a micro-fiber cloth made for cleaning prescription glasses and use that regularly.

By now, most people (even non-Apple folks) understand the basics of using the touchscreen: drag items on and around the screen, tap to select or open, pinch to zoom out, and spread two fingers apart to zoom in. But even if you’re new to it, you can become proficient at the intuitive operations very fast.

The iPad itself appears to be quite sturdy, and the aluminum-and-glass case is well-sealed. However, Apple does not claim it is waterproof, and if the water sensors within the unit are tripped, Apple will void the warranty. Our PS testers have carried one during nine months of cruising with no problems. You can always stuff it in a gallon-size zipper-lock bag for wet dinghy trips, or buy one of the waterproof cases available. We’ll be testing several of these for a future issue.

We recommend getting at least one of the many available cover-cases, which will give a little impact protection if you drop it or (as in our case) the cat frequently knocks it off the chart table.

The built-in touchpad keyboard is adequate for most uses, but if you’re writing a novel or given to long e-mails to your grandkids, an external keyboard is desirable. You can get a “dock” with keyboard, but a better choice for most people will be a blue-tooth keyboard that connects wirelessly to the iPad. We particularly like Apple’s blue-tooth unit—very compact and easy to use, for $69 from the Apple store. It’s not full-size but about the size of the keyboard on a Netbook, and nicely designed. It runs seemingly forever on two AA batteries.

There are two versions of the iPad2: WiFi only and WiFi plus 3G. If you’re using it on board, you’ll want the 3G version, which has a built-in GPS receiver that the navigation apps use. Apple is very secretive about the innards of the iPad, but apparently the GPS chip is part of the 3G-phone/data circuit. They call it “aGPS” (for “assisted” GPS), which confuses people. The assisted means that the 3G signal from cell towers will help locate your GPS position initially. But the GPS works fine without a cell signal at all—it just takes a bit longer to acquire a position upon startup. With a cell tower in range, position location generally initiates within 30 seconds. Without a cell signal, first acquisition of the GPS position can take as long as 2 minutes, though 1 minute is more usual.

The “assisted” part also acquires and stores information about the location of satellites via the cellular network, so the GPS receiver doesn’t have to download it. Unlike even simple GPS handhelds, you can’t “see” which satellites the GPS is using. Nor can you check the accuracy of the signal, a key feature in some scenarios.

We have not been able to see or measure any difference at all between GPS-only or assisted-GPS, either in locating position or displaying our boat movement. The different nav apps frequently reported very different “horizontal position errors” (as much as 50 feet difference) while in a fixed location, for reasons we could not fathom.

The iPad’s GPS chip is probably a single-channel, fast-sequencing receiver, but it seems to work as well as the multi-channel receivers. (Apple has so far managed to keep its GPS chip details a secret.)

If you already bought the WiFi-only version, you can get an add-on GPS receiver, but it will be cumbersome and a bit of a hassle to get it to work with the available apps. PS readers have reported good results with the Bad Elf GPS (www.bad-elf.com). All iPads also have a built-in compass, three-axis gyro, and accelerometer, which are used in some of the apps. The compass is mostly a nuisance, in our opinion.

There are several options for the amount of memory you can buy. Out of old habit, we bought the max available, 64 gigabytes, but have found that it was overkill. With 50 or so apps, including 14 nav apps, all of the U.S. NOAA raster charts and most of the vector charts, several hundred books, 1,600 photos, quite a bit of music, and several hundred assorted documents, we use less than 11 of the 64 gigabytes. If you’re going to store tons of movies and 20,000 songs on the iPad, you might use up 64, but most people can get by with less.

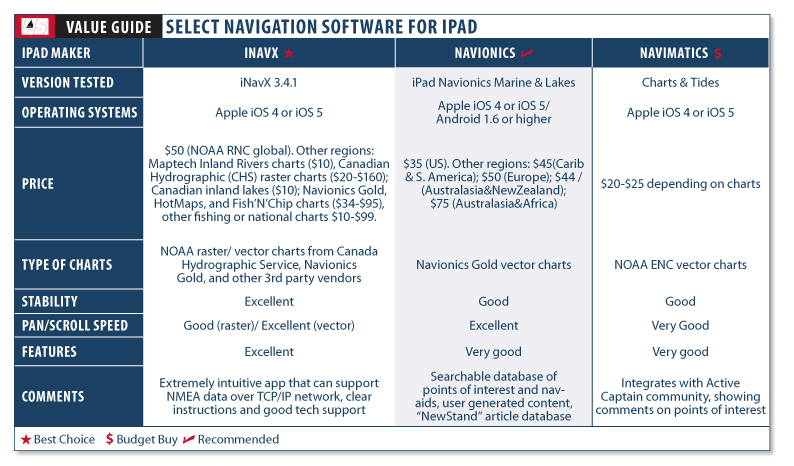

We count 308 apps directly aimed at sailing, racing, or cruising. And of course, there are many others—such as the weather apps—that will be of interest. This month, we’ll look at the three of the most popular and well-established navigation applications, representing a fairly good cross-section of what’s available on the market. Next month, we’ll look at some up-and-comers, as well as the free or nearly free basic navigation apps. In Part III, we’ll look at weather apps and other handy sailing products.

Some people ask us about similar apps for the iPad competitors, such as the Kindle Fire, Kobo Vox, or Sony, and the answer is “not yet.” With 38 million potential customers, developers are spending their efforts mostly on the iPad. One of the apps we review next month, EarthNC, however, is available as an Android app.

Photos by Ron Dwelle

222

Nav Applications

With its 6-inch by 8-inch screen (9.7 inch diagonal), the iPad has as big a viewing area as many stand-alone chartplotters. With suitable apps, the iPad works much the same as all available chartplotters, with the normal functions people have come to expect—current position, speed and course over ground, waypoints and routes, tracks, anchor alarm, and so on. Many of the navigation apps have add-ons such as weather overlays, displays of heading and speed, tide and port information, ability to e-mail your current position, satellite overlays, and so on.

Unlike most of the iPhone nav applications, the iPad apps download and carry the charts in memory so that you don’t need an Internet connection to view or use them.

One thing that the iPad doesn’t have is a wired interface (for example, through NMEA protocols) to other nav instruments such as radars, AIS receivers, autopilots, or multi-displays. A few of the apps can be networked, but you need to set up an on-board WiFi system and communicate through that. An on-board PC or Mac can act as a router, allowing one-to-one connection between the PC or MAC in iNavX. This is called ad-hoc mode.

Our testers have used the iPad as a primary chartplotter on board during two summer seasons on the Great Lakes and one winter season in Florida and don’t regret investing in the iPad rather than a chartplotter, especially when they consider all the other uses for the machine.

How We Tested

We tracked down 14 navigation apps that will convert your iPad into a chartplotter (and we may have missed a few in the Apple catalog of over 300,000 apps). We’ve examined and used all 14 of them, and found only a few that we can strongly recommend: the best operate like dedicated chartplotters; a couple work like simpler plotters, often with some functions that people might like, at a lower price. This article focuses on three of the most popular top-shelf apps.

We tried them all out to get a general impression of user-friendliness, then did a series of tasks (downloading charts, entering a waypoint, creating a route, opening new charts, zooming the charts, and creating a track of our movement). On all the apps we recommend, these functions work well, but differently. We found it difficult to say whether one app was noticeably superior to another in doing the basic tasks—you’ll just have to learn the procedure, which in most cases, is not complicated.

When available, we checked the add-on features, such as satellite-image overlay or marina information. Users have to decide whether these add-ons are necessary—one thing they definitely do is increase the learning curve for using the app, and we often think all the extra frills are overkill. If the app shows you exactly where you are on a chart, your course and speed, your track, how to steer to the next waypoints on your route, and your ETA—that’s probably enough nav information for most sailors.

With less than two years in existence, most of the nav apps are works-in-progress, and users can expect continued updates.

Probably the major basis for choosing one nav app over another is the charts you choose. Raster charts are one type; vector charts are the other. A very clear concise explanation of the differences is on NOAA’s website: www.nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/mcd/learn_diffRNC_ENC.html.

Raster charts are basically like scanned images of paper charts (actually, the original files from which paper charts are printed) with metadata added so that nav software can report lat/lon coordinates and other chart information such as depth and measurement units, as well as calculating bearings and distances.

Vector charts are “layered,” with types of information grouped together, following an international protocol (S-57)—depths in one layer, bottom characteristics in another layer, other navigational objects in another. The nav software can select and display these layers in many different ways, so it can customize the display. Most of the “layers” are provided by NOAA, but proprietary companies like Navionics, C-Chart, and Garmin, can add information layers, such as marina information, photographs, and so on.

Each type has its advocates, and the choice is to some extent personal and subjective. Those who like and are used to paper charts will prefer the raster charts. Those more familiar with Navionics and Garmin software may prefer the vector charts. As far as we know, there isn’t yet an iPad app that uses Garmin charts.

Vector charts are seamlessly quilted together so that you can drag, zoom, and pan big distances without having to close one chart and open another. On a raster chart, when you’re moving and get to the edge of one chart, a new chart has to open. (The software does this automatically in our recommended apps.) However, when planning (not navigating), you have to open the charts individually.

Photos courtesy of iNavX

256

iNavX

INAVx is the original and still one of the best navigation apps for the iPad. At $50, it is also one of the most expensive. The company was started by Rich Ray in Oregon back in 2002 when Apple brought out its OSX operating system. His GPSNavX and MacENC are still the standard programs for navigating on Macintosh computers, and Ray was the first to have a fully developed app for the iPhone and iPad. He’s been exclusively Apple, in contrast to many of the other app developers who are PC-oriented and interested in Google’s Android, Microsoft’s Windows Mobile, or other operating systems. His is a small operation, and Ray frequently responds almost immediately to e-mail questions about the software.

The program comes with no charts, but users can easily download into the iPad’s memory any or all of the NOAA raster charts (free, with complete U.S. coverage), and updating is easy. (It’s best done with a fast WiFi connection rather than a 3G cell signal.) For those who prefer vector, iNavX can do that, too. Other charts can be downloaded including Maptech Inland Rivers charts ($10); Canadian Hydrographic (CHS) raster charts ($20 up to $160 depending on the areas); Canadian inland lakes ($10); Navionics Gold, HotMaps, and Fish’N’Chip charts ($34 to $95, depending on the region and package); NV-Verlag (German) charts ($44 to $199, depending on region and package); Hilton Fishing maps ($99); Brazil’s raster charts ($10); and Finnish and Swedish charts ($99 each). The free NOAA rasters will be all that most sailors need.

Downloading non-NOAA charts (as well as transferring waypoints and routes) depends on the X-Traverse website (www.x-traverse.com), operated by the Fugawi people in Canada. You have to buy a $10 annual subscription to use the site, and of course have an internet connection (through WiFi or 3G cell) to use it. Our experience is that a good high-speed WiFi connection is desirable—almost necessary—for downloading and updating charts, and we wish that we could handle waypoints and routes directly through a cable to iTunes on our home computer, rather than through the website.

Chart navigation works very much like standalone chartplotters. Users begin by choosing a chart area (e.g. NOAA East Coast). The software will open the chart where you are located, and you’re navigating.

At the bottom of the screen below the chart are seven icons: “chart,” displays the chart; three separate icons to let you create and manipulate “waypoints,” “routes,” and “tracks”; “instruments,” presents an instrument-like display of nav information; “forecast,” for retrieving tides and GRIB information requires an Internet connection); and “guide,” the very good help manual for iNavX.

Above the chart is a series of small boxes displaying speed over ground, course, lat/lon, time, and so on—these will change depending on which function you are using. You can customize or eliminate the display altogether.

Navigating with iNavX is straightforward, and anyone with experience using a GPS, Loran, or chartplotter will be immediately competent. You can set up the display any which way—adjust the size and color of icons; choose which icons to show or hide; show the track; adjust the direction-vector size; and so on. The few different wrinkles involve the touchscreen. You zoom in or out on the chart by pinching or finger-spreading; you can “drag” the chart up, down, or sideways (boat-centered is the default); you tap on the screen to create, name, edit, or move a waypoint. The raster charts are crisp and sharp on the iPad screen.

All in all, it functions like all the top-end chartplotters—about the only thing you cannot do is overlay radar images or open multiple windows to show a fish-finder or video cam. You can get other NMEA feeds (apparent/true wind, autopilot, etc.), but you need to set up a WiFi system on your boat—the iPad will connect to the WiFi router, and if the other instruments will connect to WiFi, they will communicate with the iPad.

User-friendliness is of course subjective, but we consider iNavX to be at least as well designed as and, if anything, more user-friendly, than any chartplotter we’ve seen. It lives up to Steve Jobs’ requirements for good design and usability. Almost all the complaints we’ve heard relate to the touchscreen aspects of operation and not the software itself—some people just don’t like it or don’t want to develop their finger mechanics. One woman we talked to disliked it because her long fingernails kept her from tapping the screen properly, although we’ve not seen too many sailors with long fingernails. The customer reviews on the Apple App Store are universally positive, and it’s noteworthy that the developer seems to respond almost immediately to any concerns that users express.

One shortcoming of raster charts is that for planning, it’s hard to scroll or drag to adjacent charts—the vector charts are much better for that.

Bottom line: iNavX concentrates on the essentials and does it well. It is our top choice, even though it is pricier than the other nav apps.

250

Navionics Marine & Lakes

We liked the Navionics app for the iPhone when we reviewed the apps in April 2010, and its $35 iPad version is also good. It has full chartplotter operations and is mostly comparable in user-friendliness to iNavX.

It uses the well-known Navionics vector charts. Although all vector charts are based on NOAA data, they are not all alike, depending on how the company manipulates and displays the data. Perhaps because of their longer experience, Navionics seems to do it better than the other vector chart programs.

More than just charts, the Navionics vector format allows you to call up tide and weather info and overlay satellite and Bing images on the charts. There’s a large database of marine “points of interest” (mostly nav-aid waypoints but also marina and anchorage info and photos), an ability to e-mail, tweet, or post on Facebook your current information. In some areas, the additional geo-referenced data is spotty. For example, our nearby public transient marina is listed as having “no transient” dockage, and several nearby popular crowded anchorages that we enjoy are not shown, but Navionics is working to build that database.

Two relatively new additions are a “community layer” of user-generated content (UGC) similar to the popular Active Captain (first reported on in PS December 2009), and a “NewStand,” featuring a range of magazine articles, many of them geo-referenced. Since the UGC feature was launched in the spring, Navionics reports that it has attracted more than 6,000 registered users who have contributed more than 100,000 new objects. The NewStand now has close to 100 different publishers signed on, and is growing weekly.

In use, the app handles like a normal chartplotter that, so long as there’s an Internet connection, is always updating its data. Superimposed on the chart with your current GPS location shown, there are buttons on all four corners: search, zoom in and out, GPS location, and settings. Across the bottom are buttons for track, info, distance and bearing, and route. The info button let’s you call up weather and tide info, as well as the “NewStand” articles, earlier tracks, favorite locations, etc. Underway, a box pops up in the upper left corner, showing speed. Oddly, course or course-over-ground, which are shown on almost all other apps , doesn’t appear.

One of the most interesting features is the ability to bring up detailed “hidden” information on specific chart features. When you tap on the screen, a cross-hairs appears. You drag the map so that any feature shown (such as a buoy or marina) is in the crosshairs, then tap a button and the information on the feature pops up. This ability to show or hide metadata is a main feature of vector charts, compared to raster charts. Users also drop their own “markers” using the cross-hairs. We found this to be a good way to retrieve the additional vector info.

The program crashed twice on us during a week’s use. Crashing was rare, but it was not unusual in all the vector-chart apps we used. Navionics recently issued an update to be more compatible with Apple’s latest iOS5 operating system, which apparently changed the method of storing information, so perhaps that was the problem.

Navionics will sync to some Raymarine chartplotters, but iNavX is more powerful when it comes to displaying NMEA data on boats that have an onboard TCP/IP networks.

The other shortcoming of Navionics is that the help guide is weak—oddly arranged and not always well-written. For example, the cross-hairs—which are immediately obvious to anyone touching the screen—was not listed in the help index, and we finally found the info buried well down in the text. Fortunately, the app is intuitive enough that it was not a major problem.

Bottom line: This is the most full-featured of the vector-chart apps, so if you want all the benefits of vector, Navionics will be preferable to iNavX. Otherwise, iNavX is a better choice, more sophisticated and user-friendly.

369

Charts & Tides

Developed by Navimatics, maker of Garmin-compatible digital charts for chartplotters, Charts & Tides is a relatively inexpensive vector-chart app ($20-$25, depending on chart package). Its chief appeal may be the inclusion of “Active Captain” (www.activecaptain.com) info in an easy-to-use interface, for those who like this cruising information and want a vector chart. Once you complete the free registration for Active Captain, not only can you view the Active Captain “markers,” but you can also add to the information while in the app. You’ll want to update the Active Captain database occasionally, when you have a good WiFi connection. This is a better interface for Active Captain than eSeaChart, a lower priced product featured in the July 6, 2011 Inside Practical Sailor blog post.

There are a couple peculiarities about the charts. Most noticeable is that buoys and lights aren’t colored and labeled (such as a red buoy, with “8A” next to it)—they’re all black icons with no labels. If you tap on the icon, the complete information appears in a pop up, but we had a hard time adjusting to a chart that doesn’t show the conventional labels. Also, with the Active Captain markers activated, things can get confusing when there’s lots of information on the screen, and the little black buoy icons can get lost.

You’ll also want to check the website to see which charts come in which packages. For example, “US East” covers the east coast and all of Florida, but also has parts of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario—it does not include the Okeechobee waterway in Florida. The Gulf package includes all of Florida except for the Okeechobee waterway. The waterway, although laced with Active Captain posts, does not appear in any chart, as far as we could tell.

An unusual function is what they call a Horizontal Situation Indicator (apparently from an aviation instrument). It’s a way of showing cross-track error graphically. Most apps don’t bother with cross-track error, since it’s clearly visible when your boat’s icon is moving on a course-line you’ve entered on the chart.

A major shortcoming of the app (in our view) is that there is no “route” function—you can “go to” only a single waypoint. This is true of several other lower-priced nav apps, which we will be looking at in greater detail next month.

On the positive side, the app has a fine “search” function—you can search by name for chart features (places, marinas, buoys); you can “bookmark” features you’re likely to revisit; and you can find the nearest tide and weather stations. In addition, the info boxes that pop-up (for example, for buoys, tides, or weather) are compact and well-done. The “tide” window is better than most of the apps that are devoted exclusively to tides.

There is a good user guide included (under the information icon). You can also download a PDF copy from the company’s website, and you may want to do that before buying the app.

Bottom line: For those committed to Active Captain, this is a good choice. Vector-chart fans will like its price, but we’d be inclined to spend the extra money for Navionics. As a chartplotter, Charts & Tides is very similar to the lower-priced nav apps we’ll review next month.

Conclusion

All three of these apps earn our recommendation. Which one is best for you boils down to your preferences. If your budget allows, you might consider two. A good navigator, after all, never depends on a single source for navigational information. The original iNavX gets the prize for simplicity and overall utility. Its emphasis on key navigation functions and important extras like interfacing with NMEA devices, which can include everything from autopilots to automated identification systems, highlights its chief mission. Capable of using both vector and raster charts, it also allows a great deal of flexibility. If the next level of vector charts, a huge points of interest database, and being interconnected via Facebook and e-mail is where your interest lies, then Navionics fits. Finally, if you want to take advantage of Active Captain’s user-generated content, then Navimatics Charts & Tides is your best choice, but there are better options for navigation. If you’re still undecided, you might want to wait until next month’s report on navigational apps under $20 (several are free or nearly free), which let you test drive with little or no investment.