To many sailors, single-sideband radio falls into the black arts category, those mysterious nautical skills (like anchoring or bleeding air from your diesel engine) that are discussed in hushed, reverent tones among bowed heads at most any dockside potluck or tiki bar where cruisers tend to congregate.

That certainly may have been the case 20 years ago, when operating an SSB radio involved more knob-twirling and switch manipulations than the translation machine from Mars Attacks! But the times have changed and modern SSB models are as easy to operate as that new smart TV in your main cabin. With features such as pre-loaded channels, Digital Selective Calling on distress frequencies, memorized access to email frequencies, and automatic tuners, todays SSB radios are undoubtedly more user-friendly than ever.

Back in the 1980s and 90s, the sailor who opted for long-range communication offshore had only two practical choices: amateur ham radio or marine single sideband. A minority of trans-oceanic sailors opted out, usually because of cost. Today, however, satellite communication has reached an attractive price point, prompting some cruisers to consider it as a first choice for staying in contact with the outside world.

Illustration by Regina Gallant

Does that mean SSB is going the way of the dinosaur? Hardly. Annual surveys like those carried out by the Seven Seas Cruising Association (SSCA), indicate that SSB radios are still a favorite means of long-range communication among cruising sailors. And for inexpensive text emails and long-range voice communication around the world, the SSB radio, pumped up with a few accessories, is hard to beat.

In this, the first of our multi-part series on long-range communication, well offer a general description of SSB systems -from what they are to what they can do for you, and a snapshot of the current players in this market.

SSB 101

Developed by international agreement in order to safeguard ships and mariners, the Global Maritime Distress and Sailing System (GMDSS) divides the worlds oceans into four sea areas and stipulates the minimum communication equipment required to comply with GMDSS within each area (see map, page 21). Although GMDSS does not apply to recreational boats, common sense dictates that a prudent mariner will have the equipment thats appropriate for their intended cruising area.

The average weekend sailor will find that a marine VHF radio is more than adequate for their communication needs. A 25-watt VHF system in good working order has a range of 12 to 25 miles, which is plenty of coverage for those local trips, as well as the occasional coastal cruise. Further offshore, the familiar GPIRB or EPIRB emergency beacon is the distress alert, but this is useless for two-way, non-emergency communication.

For those venturing farther from shore who want a reliable two-way communication link within the GMDSS sphere, another form of long-range communication is needed. One choice is the relatively expensive Inmarsat satellite system used by commercial shipping. These systems require initial outlays of several thousand dollars, as well as annual network fees. For the moment, dedicated text-only transceivers like the Inmarsat Mini-C terminals offered by KVH and others are the most affordable satcom devices that are GMDSS-compliant.

A second choice the SSB. Like the VHF, the SSB is integrated into GMDSS with frequencies dedicated to maritime use such as distress calling. Whether you want port or weather information or assistance in handling onboard emergencies (an injured crewmember or even an abandon-ship scenario), long-range SSB communications help reduce the risks of long-distance sailing.

SSB is also known as marine high-frequency single-sideband (HF SSB), a name derived from the frequency range it uses, the HF range of 3 to 30 megahertz (MHz). Medium Frequency (MF) is located below the HF bands at .3 to 3 MHz, while Very High Frequency (as in your VHF radio) is above at 30 to 300 MHz. (See adjacent article Im With the Band.)

While marine VHF radio output power is limited by law to a maximum of 25 watts, the output power of a marine SSB system found aboard a typical, mid-sized cruiser is usually between 100 to 150 watts of peak envelope power (PEP). More powerful units exist, but they are expensive, heavy, and are generally designed for use aboard larger vessels.

Unlike the line of sight transmission of your VHF, SSB is a type of amplitude modulation thats ideally suited for long-range communication that can bounce or skip off the ionosphere. (See illustration.) In this manner, the radio signals don’t follow the earths curvature as would an ordinary groundwave. Instead, transmissions in this spectrum can bounce off the ionosphere and return to earth hundreds or even thousands of miles away.

When combined with the right time of day and frequency, a single-sideband or ham radio with 150 watts of power can deliver, under the right conditions, a signal that can literally be heard around the world. Keep in mind, however, that the right conditions don’t always coincide with the worst conditions on board, when you might in fact need help. That EPIRB is there for a reason.

Portable Satphone vs. SSB

Although the SSB radio has long been a fixture aboard offshore cruising boats, new portable, compact text-only devices like the SPOT, the DeLorme inReach, and portable satphones that tap into global satellite networks are drawing renewed interest from cruisers, particularly since equipment costs have dropped. Of the wide range of satellite communication devices we have tested, portable satellite phones are the most viable, affordable option.

Satphones have become particularly attractive since the introduction of affordable (or at least more affordable) service plans. (For a roundup of our coverage of satellite communication devices, see the Sept. 2, 2014 blog post: Preview of the InReach Explorer.)

Comparing a satphone to an SSB can irk the hardcore radiophile. Although some of their functions overlap, it is an apples-and-oranges comparison. One chief difference between a portable satphone and single-sideband radio is that the former is typically point-to-point device-one caller contacting one or more designated recipients. An SSB transmission can be received by any device within broadcast range listening on that frequency. As with any apples-to-oranges comparison of two different systems providing similar functions (both SSB and a satphone can deliver voice communications and email, for example) both will invariably have their pros and cons.

Operationally, the most obvious advantage of a satellite phone is its familiar form and operation. Even a non-sailor who has never used a VHF can probably figure out how to use a satphone. Another advantage is that its easy to call a landline phone with a satphone. (This is also possible with an SSB using services like ShipCom). And, for the sailor who likes to do his own installations, the satellite device greatly simplifies setup.

A satellite phones portability is also a plus. You can bring it on shore excursions, or even bring it with you should you need to abandon ship.

There are also cons to handheld sat phones: just like cell phones, handheld portable satphones are not integrated into GMDSS. Neither is meant to provide ship-to-ship safety communications or communications with rescue vessels or aircraft. Private party contractors like GEOS Alliance will help route rescue calls placed via satellite devices to the Coast Guard, but the U.S. Coast Guard doesn’t advocate cell phone or satellite phone as a primary means for making distress calls. They have proven, however, to be a very effective backup.

One of the main reasons sailors choose a marine SSB over a satellite phone is so that they can participate in various regional safety and cruising nets that allow cruising sailors to stay in touch and share local knowledge-and if needed, ask for help. You don’t, of course, need a transceiver to simply listen to these stations or nets-an ordinary portable multi-band radio that can tune into SSB frequencies will do.

An additional safety benefit of the modern SSB is Digital Selective Calling (DSC). DSC is an essential element in GMDSS. All commercial ships mandated to have DSC are required to monitor DSC marine SSB frequencies while at sea. In the event of an emergency, they (or any other HF SSB DSC-equipped vessel) would receive your exact location (assuming youve provided GPS data to your SSB) and nature of distress at the push of a button.

As with VHF DSC, the DSC function effectively takes the search out of search and rescue, allowing rescue agencies (or nearby Good Samaritans) to provide immediate assistance, rather than waste valuable time trying to locate you first.

Although direct cost comparisons between SSB and satphones will depend on the particular unit or system being considered, its fairly typical to find that the initial cash outlay will likely be a bit less for a portable satphone (particularly if installation costs of the SSB are factored in). However, a more accurate assessment is lifetime cost, which can be determined by factoring in the costs associated with each system over the years.

For over-the-counter portable satphones, lifetime cost ultimately depends on the service plan selected, but at a minimum will mean hundreds if not thousands of dollars in annual, recurring costs. For SSB, unless youre utilizing some type of commercial service (for weather routing, email, etc), transmitting and receiving over the airwaves is free, and free is good. (Inmarsats Mini-C system allows a wide range of uses within the network at no cost, but these are text-only devices.)

The Players

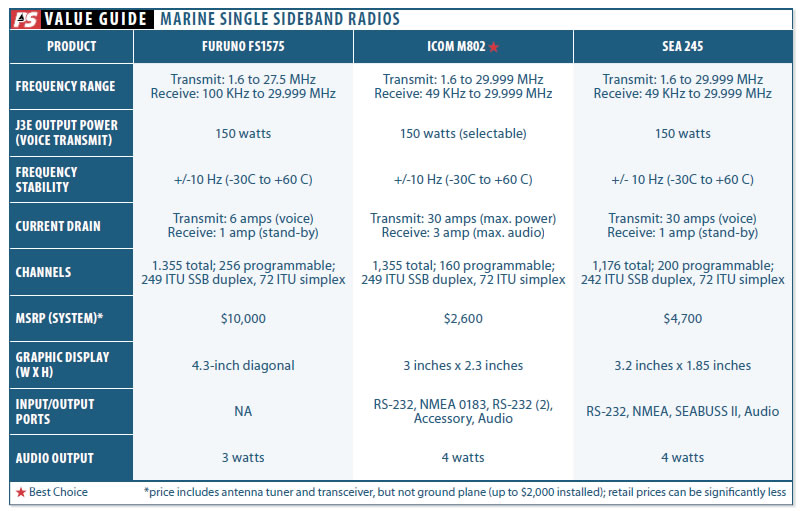

There are very few apart from Icom manufacturers in the U.S. that offer SSB radios that target recreational boaters. Based on survey information, we looked at products from Furuno, Icom, and SEA Com Corp. Of these, Icom carries the lions share of the market and their Icom M802 SSB radio is by far the bestselling SSB unit on the market. Other options include the JRC JSS-2150 MF-HF-DSC-SSB, or the incredibly expensive Sailor / Thrane & Thrane model 6300 MF/HF-DSC-SS, but the fact of the matter remains that Icom is the only true player in this market.

SEA 245D Continuous Duty MF/HF SSB Digital Radiotelephone

The SEA 245D system consists of a 2451D RTU, a 2450 Remote Control Head, and a 1612C automatic antenna tuner. The SEA 245D can control up to four remote heads for those needing multiple control locations. The manufacturer describes the SEA 2451D as a highly integrated and compact solid-state MF/HF SSB transceiver housed in a ruggedized chassis specifically designed for long duration transmit cycles.

The Sea 245 only has DSC functions on MF/2187.5khz and not on any of the HF-DSC frequencies, making it a product for a very narrow/niche market, not one for offshore sailors nor for your typical cruisers.

The SEA 245 SSB radios are compliant for Sea Area A2 GMDSS station operations and are also suitable for any general purpose MF/HF SSB radiotelephone operation where a high duty-cycle use is required. An upgrade to SEA Area A3/A4 compliance is available.

Features include an internal DSC controller and medium-frequency watch receiver; factory- and customer-programmed channels with alpha-numeric names for easy recall; large, easy to read graphic display; and a backlighted silicone keypad. Frequency options include marine, land mobile, and aviation channels, and amateur bands. The suggested retail price for the 2450 is $1,150, and $2,550 for the 2451. The 1612C automatic tuner brings the minimum price for the system (without ground plane) to about $4,700.

Furono FS1575

Featuring an integrated DSC/DSC watch receiver, Furunos 24-volt FS1575 is clearly targeted at the commercial market. The least powerful of Furunos three-unit series, the FS1575 facilitates both general and GMDSS communication, operating as a DSC transceiver and as a DSC Watch Receiver on all distress and safety frequencies in MF and HF bands. An optional terminal can be connected to the transceiver to handle telex operation and distress message/maritime safety information.

Other features of the FS1575 include a bright, high-contrast 4.3-inch color LCD (multiple display configurations are available) as well as a night mode (white text on black background display) for wheelhouse operation. A rotary knob or direct keypad allows instant selection of 256 user-specifed channels. Quick access to DSC message composition is available by dedicated keys on the control unit.

For additional ease of operation, users can assign three quick-access functions using 1, 4, and 7 on the numeric keypad. These are displayed on the Radiotelephone display. Settings that the user can pre-assign for quick access include transmit frequency, receive frequency, class of emission, automatic gain (sensitivity), output power, transmit frequency monitoring. Shorcuts to preconfigured displays include: list of test messages, list of message files, list of log files, and intercom functions.

The FS1575 also features a simplified menu operation. Numbers are assigned to menu items, each of which can be accessed by turning and pressing the push to enter knob to select menu items or by pressing the desired number on the numeric keypad.

The FS1575 meets GMDSS carriage requirements for SOLAS ships operating in A3 and A4 sea areas. The system consists of a transceiver (the FS1575 unit), an FS1575 control/display unit, and an AT1575 automatic antenna coupler. The system lists for about $10,000.

ICOM M802

While the Icom M802 is sold as a marine transceiver, its actually a dual-purpose, 150-watt SSB radio thats approved by the FCC for both marine and ham use with an operating range of 1.6 to 30 MHz. A basic Icom M802 system package consists of an M802 transceiver, RC-25 remote control head, and an antenna tuner (with the AT-140 antenna tuner being the most popular choice).

Features include a large LCD display with easy-to-read dot matrix characters. For nighttime use, both the display and keypad have 10 brightness adjustment levels. For fast channel selection, the control head features two dials-one for banks (groups) of channels and one for individual channels. The bank dial controls up to 16 banks of channels (up to 20 channels per bank) for user-grouped channels, and 17 banks for ITU (international) channels.

The M802 also features built-in, one -touch digital selective calling (DSC) for both emergency and direct dial communications. The M802 can also be set to memorize your HF e-mail access frequency, mode, and bandwidth settings via a dedicated email button.

The RC-25 hs ports for GPS input, a headphone jack, and a mic that allows you to remotely scroll through the pre-programmed channels.

With tuner and antenna (no ground plane) the system sells for about $2,500. At that price, it is no wonder why ICOM is virtually the only player in this field.

Conclusion

While satellite phones have carved a niche in the cruisers communication toolbox, SSB continues to be the benchmark for versatile, economical, and reliable long-range communications for those sailing toward far horizons. Satellite phones bring a lot to the table and would make the ultimate addition to any ditchbag, however the overall usefulness of SSB in providing a wide range of free information (from weather to email) is what keeps it popular.

Coming in the second part of our series on single side-band, we walk through a radio installation, and take a close look at some novel antenna and grounding options.

Is a SSB Transceiver designed for amateur radio enthusiast but with only 20 watts of output power (about $500.00 US – Xiegu G90 – Frequency Range Frequency range of 0.5-30MHz) of any use to a budget mined blue water cruiser with a smaller boat?

The G90 needs a small modification to transmit outside of HAM radio frequencies. (receiving works out of the box)

https://youtu.be/pRqQ1KQm–0

Other than that I’d be interested to hear from people who use it as a marine radio. Thinking of buying one instead of a RX only.

No. Amateur radios are not “FCC type-accepted” for the marine radio bands. The FCC says you can only use a radio specifically built to be a marine radio to communicate on marine radio bands. The internal differences between ham radios and marine radios are technical and mean more to the FCC than to the average lay-person, but the regulations prevent the marine band, which is a life-line for those who need it, from being polluted with spurious noise. Also, marine radios are designed with the power limitations of boats in mind, whereas a ham radio is usually designed to sit on a desk next to a 50 Amp power supply and a 1500 KW amplifier. If a ham radio produces spurious noise, it will annoy some hams and the operator is supposed to “self-police” to resolve the issue, but no one’s life-line communication is jeopardized.