When a sailor needs to connect point A to point B, he reaches for rope. We make an exception for jacklines because rope rolls under foot and webbing doesn’t.

Sail, canvas work, harnesses and hiking straps are made from webbing because it’s easier to sew and spreads the load better. You can use buckles with webbing, vital for tensioning Bimini tops and adjusting tie-downs.

These are the traditional applications for ropes and for webbing, but perhaps were missing out on a few key advantages that have made webbing popular with riggers.

Webbing Winds Better

On a spool, webbing leaves fewer gaps, resulting in 20-40 percent more capacity than rope, with less friction and chance of binding.

Shore ties. These are a popular application (Quickline, PS December 2006). A great length of line takes minimum space and is easily deployed and recovered. Webbing is hard to handle under load and does not absorb shock, but the main rode absorbs most of the shock and provides the actual tension. Shore ties can be slacked before disconnecting.

Dinghy rode. We keep 75 feet of 1500-pound polyester webbing on a Cuban yo-yo. Because the yo-yo provides both line storage and grip, it avoids tangling, coiling, and finger cutting. To prevent chafe, we coated the first 15 feet in Flexdel Rope Dip (see Chafe Protection for Fiber Rodes, PS October 2019).

Trailer winches. Replacing steel cable with webbing reduces the risk of the cable slipping under load as the wraps tighten. Anyone who has seen their mast fall a few feet as it is lowered with wire using the trailer winch (with a gin pole) knows what we are talking about.

Fewer Furler Jams

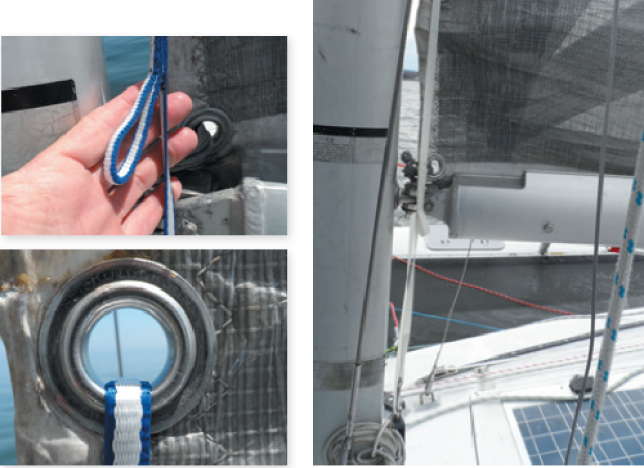

Big boat sailors experience furler jams when the line gets trapped under looser turns, necessitating a trip to the bow. Again, the cure is furling under consistent tension. However, these problems can also be prevented by using webbing because it is wider, so it doesn’t dig down through the previous wraps, slip, or foul.

The reacher furler on our test boat is the same size as the jib furler, but the foot of the sail is much longer, requiring more furling line on the drum.

No matter how we adjusted the amount of line on the reacher furler, the drum would either fill and jam before the sail was unfurled, or we would run out of furler line before the sail was completely furled, particularly in higher winds, when the load is higher and the sail wraps more tightly. We cured this by converting the first 15 feet to webbing. We can now furl the sail, with turns to spare, even after wrapping the sheet around the sail the customary 3-5times.

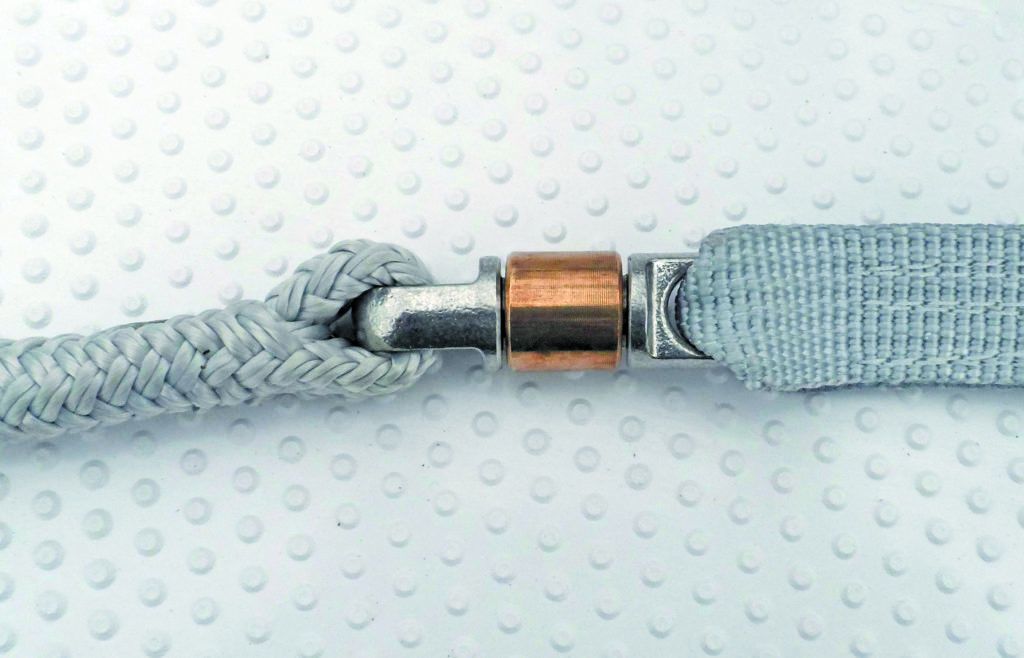

The Facnor Flat Deck furler uses webbing instead of rope to make a furler with a lower profile, allowing for a lower tack, which is attractive to racers. Webbing is guided onto the spool with a special narrow guide, and brass rope-to-webbing adapter makes the transition smooth.

A more common solution is to strip the core, after which the rope flattens out a bit like webbing. It runs smoother through the fairleads than the webbing/rope splice, but does not spool as efficiently as webbing. A good compromise.

Bends Better, Stretches Less

Climbers often use webbing for wall anchors instead of rope because it has better strength over sharp edges. When a rope is loaded over thin edge it can lose over 70 percent of its strength, while webbing will lose very little. The reason is that the ratio of bend radius to webbing thickness is much kinder than for a rope of equal strength, and as a result, all of the fibers keep working.

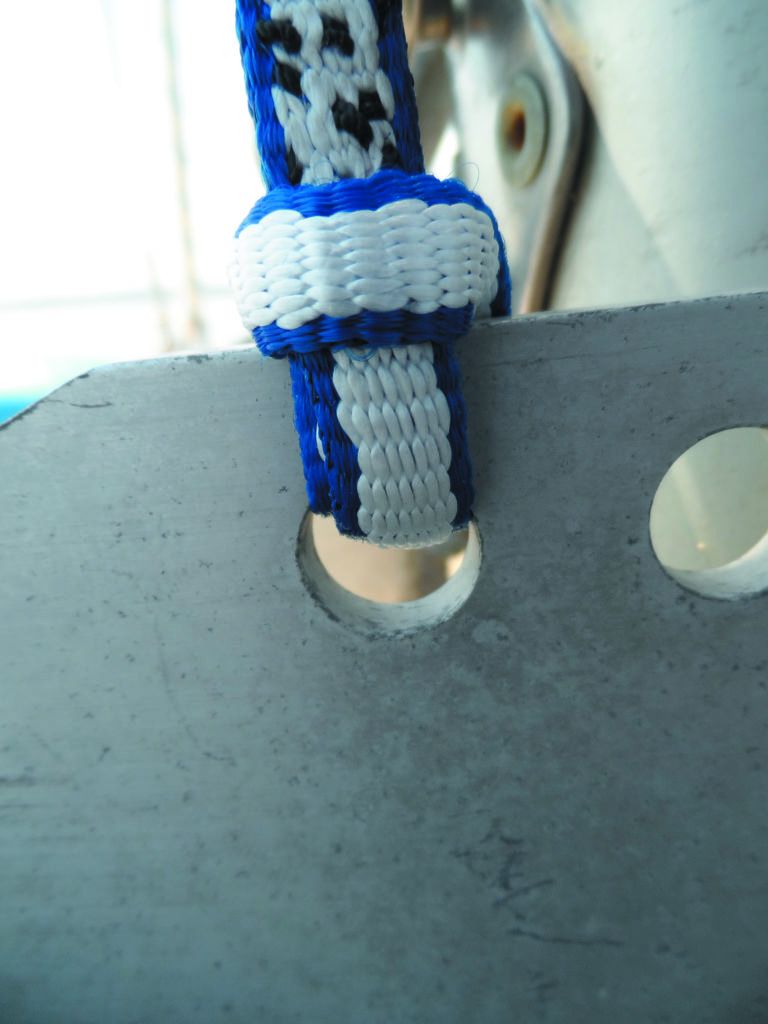

Related, but often forgotten, is that rope generates massive internal friction when asked to run around a sharp bend under high load, like a reefing eye or Cunningham eye. Webbing of the same strength, on the other hand, doesn’t see the grommet as a sharp turn at all, and runs easily. As a result, a webbing strap through the Cunningham grommet is lower in friction and is an easy way to add 2:1 advantage.

The primary factor in stretch is the base material (for example, nylon stretches three times more than polyester), the weave also makes a big difference. Nylon webbing has only half the stretch of nylon double-braid rope, and one-third the stretch of climbing rope.

Spreads the load

Although obvious with hiking straps and harness, there are more applications.

Hand holds. Like the hand holds above car doors, webbing makes a better hand hold for a given size. We like webbing for kayak painters, since we pull them on deck using a loop at the end. We like narrow webbing for finger pulls on pins on adjustable lead cars and snap shackles.

Thigh braces. These are key for sit-on kayaks, an obvious application (see PS October 2017, online). Its impossible to paddle a kayak with power and control if you are not braced.

Lashing Blocks and Low Friction Rings. In Low Friction Rings (see PS April 2018, online) we demonstrated securing low friction rings using climbing slings. It is easy, fast, inexpensive, and the lower profile of webbing makes it very secure. It can also be used for lashing blocks. If sewn or whipped short and tightly, you will reduce wobble; whether this is good or bad depends on the application.

Curiously, webbing has little advantage running through low friction rings. Dyneema single braid, such as Amsteel, flattens out much like webbing and runs smoothly-but barely stretches, a pre-requisite for most running rigging (except halyards).

Here are some other possible applications.

- Genoa clew. A sling can be rigged to ease the clew plate away from stays, reducing snagging.

- Attaching a snubber line to anchor rode using Prusik hitch. Proven by generations of climbers to be the fastest and most idiot proof gripper hitch.

- Slab reefing outhaul tackles. Less friction through the clew grommet orring.

- Control lines. Are there control lines that would be safer underfoot if made from webbing? Not many. Sheets must stretch to dampen shock loads. And webbing can’t be used in a jammer or cam cleat, or in a winch. Additionally, joining webbing to rope is problematic, so stripping either cover or core is more popular and practical in most cases.

- Lashing to toerails. Little strength is lost at the sharp bends.

Conclusion

Horses for courses. The majority of the line on sailboats will always be rope, but perhaps there are a few places where a flat sort of rope is the better answer. Also consider the downsides. UV does more damage to webbing because it is thinner than rope, reducing the life expectancy. Webbing doesn’t work well in standard winches, although it does very well with captive winches, in the form of furlers and trailer winches. Finally, is hard to grip without a loop.

Avoid webbing in bosun chairs. I had the webbing fail when I was at the top of a 60ft mast. Fortunately I was also wearing a full body harness (which paradoxically also uses webbing- albeit newer).

Often sailing single handed I have a line set up running outside from the bow cleat to the main winch with a (old climbing) sling attached mid length using a prusik hitch. Slipping the sling over the mid dock cleat went along way toward getting the boat secured

Your photo for “Webbing uses (clockwise from top left)… webbing loop at the jib clew prevents snags (soft-shackles join each sheet)…” is not very informative. I can’t see which part is made of webbing, nor where the blue lines go. Do you have a better photo or diagram?

I’d also like to see how the webbing and jib furling line come together in more detail. Thanks for a great post.

Webbing works well when connecting things to spars temporarily. I’ve rigged a clip on preventer attachment to a main boom and have rigged a headlamp to the mast to be angled up to illuminate telltales on the jib.

I’ve added larger photos. Captions to come. If you download November 2019 issue in which this article originally appeared, I believe there are higher resolution images that will explain better, also. https://www.practical-sailor.com/subscriber-only/download-the-full-november-2019-issue-pdf

The webbing on the jib sheet is a simple loop with stitched splices, basically an extension to which the jib sheets attach. The webbing and furler line can be stitched or use a swivel union described in the caption. A more common solution is to remove the core as described (make sure to stitch the core to keep from slipping). I’m not sure which blue lines you are referring to, this report is really a round-up summarizing several articles we’ve done on webbing and stitched splices. If you search under the specific topics (snubber, clew strap, snubber, jackline, etc.) there is more detail on each.

https://www.practical-sailor.com/?s=webbing

I often replace aging metal grommets by sewing on a single-twisted bight of webbing. It can be sewn on at whatever length/angle best distributes the impending loads, and it reinforces the original material where the rotten grommet has left a weak spot. (Gives a much stronger connection point than the grommets on most tarps, and works great for sail hanks/sliders as well!)

I have observed that for crane launched boats ( single hook on shore crane, to which is attached a sling of multiple strands, each in turn hooking to hard lifting points on the boat ) the sling is often made of webbing not rope.

Would you say that webbing is superior to rope in this application, and if so, why?

I posted larger images, and we’ll add the captions tomorrow. You should be able to match them up from the grouped images for now.

A very informative article. Could you provide some sources for webbing? I’m guessing Sailrite but any others?

To answer Boyte’s question:

Try these ‘trucking suppliers’ for webbing

(1) http://www.uscargocontrol.com

(2) also, google ‘shippers supply’