A lot of woven fabric is needed to keep a boat looking good and to protect both equipment and human skin.

Despite a host of new fabrics conjured up by chemists, cotton duck is still a favorite, and the textile industry makes many miles of it each year. Cotton’s enduring quality is that it feels good. And it’s not expensive to make or to replace.

Among the man-made materials, a favorite with boatowners is the breathable Sunbrella, which is woven with a solution-dyed acrylic thread. The bright-colored fabric then gets a fluorocarbon finish for water repellency. Eventually the finish wears away.

Gore-Tex, another favorite fabric of sailors, owes part of its water repellency to a very tight weave-in exactly the same manner as the famous British Aquascutum trenchcoat did with fine Egyptian cotton. Gore-Tex requires a polymer coating to make water bead up and run off. (Another famous use of swollen-fiber waterproofing is the Scottish-made coat called a Barbour Border jacket; the coat is waxed to complete the waterproofing.)

Coating fabrics (or the threads from which they’re woven) to make them waterproof is big business. You could make your own, of course. Three cups soybean oil, a cup and a half of turpentine, then mix, paint on, and dry… You will not like it.

As you read this, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor, Karen Gleason, of the Department of Chemical Engineering, is working on a process called “hot filament chemical vapor deposition” (HFCVD) to deposit nanolayers of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, a.k.a. Teflon) to a fabric or filament. Among the applications will be fine wire neural probes that can carry toxin-destroying enzymes. A fellow professor, Alexander Klibanov, is trying to figure out how to combine Gleason’s fog with his new microbe-killing molecules. The two are shooting high, but you can be sure the coating process will trickle down to boots, gloves, foul-weather gear and the fabric industry in general. (Who knows, with treated socks, they may even conquer athlete’s foot, and that would be a significant achievement.)

The eventual ultimate fabric may be made of Dyneema thread, which will be absolutely indestructible, as in Alex Guinness’s old movie, The Man In The White Suit.

True waterproofing is not what is sought in most fabrics, natural or man-made, although for many years foul-weather gear has been available in PVC-coated fabric that is essentially waterproof, from the outside, at least. This inexpensive gear is favored by commercial fishermen, but we know sailors who prefer it to the vastly expensive exotic-fabric gear sold in most of the chandleries these days.

Leaving foul-weather gear out of it, the trouble is that anything really waterproof introduces a lot of other problems involving poor bonding, deterioration, sweating, bad odors, rotting of whatever is covered, etc., and bugs love the trapped moisture.

Breathable material that excludes water but allows air to circulate is best for sailcovers, awnings, hatch covers, ditty bags, seat cushions, bimini tops, boatswain’s chairs, sailbags, life harnesses, tiller covers, life jackets, stowage bags-the list goes on.

The rub is that, being prone to mildew, grime, spiders, mold, stains, moths, water marks, and lady bugs, they get to looking something awful. They also lose their water repellency, partly from wear but also due to the ravages of the sun.

Ipso facto, fabrics need both washing and re-coating with some kind of water repellent.

The best thing to do is to not let the fabric get filthy to begin with. With good water repellency, most fabric is easy to keep clean. A very light scrubbing and good rinse does the job. Then, restore the water repellency. The maker of the fabric should supply a recommendation on the frequency, or you can check it for “beading.” You can get to be an expert with the tell-tale beading test. Use a small piece of new or protected fabric for comparison; the difference is usually startling.

Skipping over the entire subject of washing (except to advise following the manufacturers’ instructions to the letter, particularly when it comes to Gore-Tex and other breathable fabrics), this report has to do with commonly available products used to provide or restore water repellency. The one most familiar is 3M’s Scotch Gard.

Practical Sailor collected 13 products, a sizeable sampling, from chandleries, hardware stores, camping stores, and the Web. Check the chart on page 20 for the names.

Out of curiosity, we included two products that contain silicone-Granger’s Fabsil and Nikwax (a spray wax) Such sprays and liquids (along with plain old wax) are often used for tents, tarps, and other camping canvas. But silicone is an oil. It yellows with age and, because it never really dries, attracts dirt and is very difficult to clean when it gets dirty. (You can check by placing drops of both plain water and a silicone product on a bit of treated fabric. The water will bead up; the oil in the silicone will soak in and spread.)

The spray products discussed here are treated with chemically inert fluoro-polymers. (Because we just know you’re curious, the newest of these coatings is N-fluoromethanesulfonimide/N-fluorol (1,3,2) dithiazinane-1.1.3.3.tetraoxide.)

The polymers need heat to cure completely. The coating is best done in an industrial setting, but you can approximate that by doing your spraying in the sun on a good hot day.

Work in the open air and keep the spray to leeward, if possible. Most of these products are combustible and not good to inhale. The containers bear the usual warnings.

Polymers don’t bond well with anything, especially dirty fabric, which is another reason to do as suggested above-keep the fabric clean and treat it when the “beading test” first indicates it’s breaking down.

The Testing

For the first phase of this Practical Sailor testing, two varieties of light-weight cotton duck were used. (Ideally, the test might have included Sunbrella, Gore-Tex…and others like Ultrex, Helly Tech, Entrant, Weblon, Triple Point, Sunforger, Seamark, Pfifertex, Supplex, and maybe even Twilfast, a coated fabric made by the Hoartz Corp., of Acton, Massachusetts, which in 1907 came up with three-ply tops for horseless carriages.)

Both varieties of cotton duck were said by the stores where they were purchased to be untreated material. One was a thin tannish duck, the other white and somewhat heavier. In case they had some kind of light coating not known to the stores that sold them, each cotton duck piece was washed (using strong laundry detergent), rinsed thoroughly, and dried in standard home laundry machines. To make sure, the laundering procedure was repeated a second time.

To test the water-repellent behavior of untreated cotton duck, a 3-1/4″ circle of each material was cut out with scissors. The round fabric samples-marked “A” and “B” with a permanent ink marker-were used as the sealing lids for pint-sized Ball canning jars-the kind that have the sealing top separate from the ring that threads on the jar. The jars have handy markings in both fluid ounces and milliliters, with a molded-in grape design that makes it easy to check finer changes in volume.

The jars were half-filled with water, a cotton duck circle was placed on each jar and sealed with the screw-down ring. Then the jars were placed on their sides. As expected, the water quickly seeped through the canvas and made the exterior surface wet to both touch and sight. However, neither jar dripped water, even when left on their sides for several weeks.

Because the two varieties of duck behaved exactly alike, the thinner, natural tan-colored duck was used for the rest of the testing,

Curious about how far this experiment could proceed, we used Brawny paper towel squares, which were sprayed and saturated with the 13 products and dried overnight. As with the cotton duck, perfect seals resulted. Even when left for several weeks, no leakage occurred. Vigorous shaking would, of course, tear the paper towel circles.

Next came toilet paper squares. Sprayed, dried and fitted to the jars, they appeared to provide a seal equal to the cotton duck and Brawny toweling-even though the delicate paper stretched and sagged alarmingly.

After several weeks set aside at the back of a workbench, the paper towel and toilet paper samples-still not leaking a whit ,and still beading nicely when misted-were dismantled.

(The triumphant announcement to all within hearing that a way had been discovered to waterproof toilet paper got only a couple of rolled eyeballs.)

It was time to return from far afield. More jars were needed. The folks at the canning jar store got so curious that they had to be told what was going on. (They seemed like they might be about to call Tom Ridge or even Donald Rumsfeld.)

The Real Question

More than a dozen circles of the tan duck were cut and numbered. Each was treated on one side only with one of the 13 products.

One circle-#14-was treated heavily on both sides with Scotch Gard Heavy Duty, just to see if saturation made a difference. Circle #15 was left untreated, as with “A” and “B” in the earlier cotton duck comparison.

(Because the spray seemed in every case to soak through and wet the other side, treating one side only was probably futile. After the circles were dried, mist beaded on both sides of the samples. We attempted to apply the products like most boatowners might, spraying but one side of a sailcover or bimini, which would be made of heavier duck than that used in this test. In an experiment with a heavy canvas tote bag, the spray did not soak through.)

After drying overnight in the shop (68, 55% humidity) and an initial beading examination, the circles were further dried for an hour in an oven set at “warm”- which was about 200.

Finally, with treated surfaces on the inside, the canvas “seals” were set in the rings and screwed tightly down on jars half filled with water.

As the jars were upended to check for leaks, it was noted that #1 (the ReviveX) leaked immediately. Hard tightening of the ring made no difference. Three different jars and four rings were tried, but made no difference in the leaking. The moisture simply soaked through the seal, wet the canvas duck, accumulated on the outside and dripped down. (The ReviveX label states that it “Totally Restores Outerwear Water Repellency,” but also states in finer print that it is “Specifically Engineered for Gore-Tex, Windstopper and Dryloff products.”

After six minutes, the leakage stopped. The same leakage occurred with five other products, although we should note that #3, Iosso, leaked far more slowly than the others.

The remainder of the samples did not leak. The outside surfaces of the canvas seals remained dry.

The untreated seal, #15, soaked up water, dripped a few dozen drops over two or three minutes, and then stopped leaking. The sample saturated with Scotch Gard, #14, did not leak.

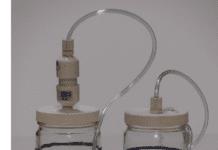

All 15 jars, with the restored water level in each carefully marked with a permanent ink pen, then were taken outdoors and placed in a rack. The rack was made to hold them on their sides (see photo on page 17), with half of each canvas seal in contact with the water in each jar.

The water levels in the jars were checked at one, two, four, and 24-hour intervals, then again after five days. The specific results for each brand are noted on the chart.

Conclusions

At the 24-hour mark, the water level was unchanged in only three jars-the British-made Nikwax, the Scotch Gard Heavy Duty, and the 303 Fabric Guard. Because it’s a wax, which accumulates dirt, we’ll discount the Nikwax. Kel Water and Stain Repellent and ReviveX had let most of the water out by that point, but were still hanging on.

At the final five-day checkpoint, the Scotch Gard Heavy Duty had given up all its water. Making the final cut were ReviveX (the product that had leaked so severely in the beginning) Kel Water and Stain Repellent (this was the version without silicone; there is also a version called “Shield” that contains silicone), and 303 Fabric Guard, which not only lost the least water in the “standard” part of the test, but is priced in line with the Kel and Scotch Gard Heavy Duty. The 303 is our winner.

It was no surprise that the cotton duck sample soaked thoroughly with Scotch Gard Heavy Duty did best of all, but it was a bit of an amazement that the completely untreated sample, as well as our experiments with toilet paper and paper towels, were so leakproof. The reason, according to manufacturers we spoke with, is that much of the success of a waterproofer depends on how thoroughly and quickly it’s absorbed by the fabric it’s used on. Obviously, waterproofed TP wouldn’t put up much of a fight against any force used against it. As for the untreated duck, it soaked up the water quickly, swelled its threads, and effectively waterproofed itself with the water itself. We all know what happens, though, if you touch the inside of a canvas tent in a rainstorm-instant leak path.

The chart originally had a column entitled “Ease of Application.” The column was dropped when, after working with the first half dozen products, little difference was noted. The pressurized cans are a little easier to use than the manual spray bottles, and they permit a more even spray. With either type, there is a tendency to overdo the spraying.

Although we originally intended to leave the jars outdoors to weather in the sun and rain until all but one failed, the results in 24 hours obviated that approach. The weal and woe of it appeared very quickly.

Value Guide: Fabric Waterproofers

| PRODUCT | CONTAINER PRICE | PRICE PER OZ. | CONTAINER | COVERAGE | INITIAL LEAKING W. WATER LEFT IN JARS | TEST WATER AFTER 1 HR. | AFTER 2 HRS. | AFTER 4 HRS. | AFTER 24 HRS. | AFTER 5 DAYS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ReviveX | $9.95 / 5 oz. | 1.99 | Manual Pump | Not Stated | Dripped hard | 1/3 Gone | 1/3 Gone | 1/2 Gone | 1/2 Gone | 2/3 Gone |

| 2. Granger's (Fabsil) | $9.95 / 20 oz. | 50¢ | Pressurized Can | Not Stated | Did not leak | 1/2 Gone | 3/4 Gone | 7/8 Gone | Gone | Gone |

| 3. losso Water Repellent | $15.70 / 22 oz. | 71¢ | Manual Pump | 27 Sq. Ft. | Soaked thru/leaked | 2/3 Gone | Gone | Gone | Gone | Gone |

| 4. Kel Water Stain Repellent | $7.99 / 11 oz. | 73¢ | Pressurized Can | 200 Sq. Ft. | Did not leak | Same | Same | Same | 1/4 Gone | 7/8 Gone |

| 5. Marykate Fabric Waterproofer | $12.99 / 32 oz. | 41¢ | Manual Pump | Not Stated | Did not leak | Same | 1/8 Gone | 1/8 Gone | Gone | Gone |

| 6. Nikwax | $8.00 / 5.8 oz. | 1.38 | Manual Pump | One Garment' | Did not leak | Same | Same | Same | Same | Gone |

| 7. Scotch Gard | $7.99 / 10 oz. | 80¢ | Pressurized Can | 1 Sofa, 2 Chairs' | Did not leak | Same | Same | 1/8 Gone | Gone | Gone |

| 8. Scotch Gard Heavy Duty | $8.29 / 11 oz. | 75¢ | Pressurized Can | 75 Sq. Ft. | Did not leak | Same | Same | Same | Same | Gone |

| 9. Starbrite Waterproofing w/ Teflon | $11.99 / 22 oz. | 55¢ | Manual Pump | Not Stated | Soaked thru/leaked | Gone | Gone | Gone | Gone | Gone |

| 10. Tectron Wet Guard | $7.50 / 11 oz. | 68¢ | Pressurized Can | 50 Sq. Ft. | Soaked thru/leaked | Gone | Gone | Gone | Gone | Gone |

| 11. 303 Fabric Guard | $22.95 / 32 oz. | 72¢ | Manual Pump | Not Stated | Did not leak | Same | Same | Same | Same | 1/2 Gone |

| 12. West Marine Fabric Protectant | $9.99 / 16 oz. | 62¢ | Manual Pump | Not Stated | Soaked thru/leaked | Gone | Gone | Gone | Gone | Gone |

| 13. West Marine Waterproofing w/ Teflon | $9.99 / 20 oz. | 50¢ | Manual Pump | Not Stated | Soaked thru/leaked | 1/2 Gone | 2/3 Gone | 3/4 Gone | Gone | Gone |

| 14. Thoroughly Soaked w/ #8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Did not leak | Same | Same | Same | Same | 1/8 Gone |

| 15. Untreated | NA | NA | NA | NA | Dripped but briefly | Same | Same | Same | Same | 1/4 Gone |

303, 800/223-4303, www.303products.com

Gore-Tex, 800/431-GORE, www.gore-tex.com

Granger’s, 44 (0) 1773 521 521, www.stay-dry.co.uk

in US, 604/220-0420, [email protected]

Iosso, 847/437-8400, www.iosso.com

MaryKate, 800/272-8963, www.marykate.com

Nikwax, 425/303-1410, watershedusa.com

ReviveX (McNett Corp.,)360/671-2227, www.mcnett.com

Scotch Gard (3M), 800/364-3577, www.mmm.com

Star brite, 800/327-8583, www.starbrite.com

Tectron Wet Guard, 877/236-8428, www.bentgate.com

West Marine, 800/262-8464, www.westmarine.com

I had been using 303 for years ahead of sailing. At $60/gallon it seems expensive but not really. Hard to put a price on what got saved from UV and moisture degradation; an expensive drysuit for one. Developed by NASA for the extremes of space flight, 303 is a miracle drug for boats. Nice that us aqua-bugs didn’t have to pay for all that R&D, just all the other tax payers (smile). For clothing that gets washed, I re-apply after second round. For stretchy rubber parts like drysuit seals, once a week if in use. Once every three months if sitting in a dark locker. I even use it on top of gelcoat and windows if there’s nothing else around. Electrical cords, dock lines, rubrails, sails, everything benefits. If 303 stays wet too long, mold will ensue. Black mold usually, but green sometimes. Go Packers.