How important is an anchor aboard a racing sailboat? Just ask Swiss sailor Bernard Stamm who was disqualified from the 2008-2009 Vendee Globe Around-the-World Race when his anchor dragged at Enderby Island, in the Auckland Islands, where he’d stopped to make emergency repairs. As his boat began bearing down on a Russian research vessel in the anchorage, the crew tried to help, at one point boarding Stamm’s Open 60. In a controversial decision, Stamm was disqualified for taking outside assistance. Since that incident, we’ve been exploring the various choices available for the racing sailor who begrudges every added ounce of weight onboard, or the short-handed cruiser who wants a superlight anchor that can be deployed by dinghy.

Racers use anchors for more than just pit stops. In 2010, Volvo Ocean Race participants used their anchors tactically to hold their yachts against an adverse tide before crossing Storm Bay in South Africa. However, the main reason a racing sailor needs an anchor is the same as for the cruising sailor: safety. Many of 2008-2009 Vendee racers used the same style of anchor that Stamm did, a 32-pound FX-55 made by Fortress Anchors. Others used Fortresss budget-priced version of the same anchor, the Guardian G-55.

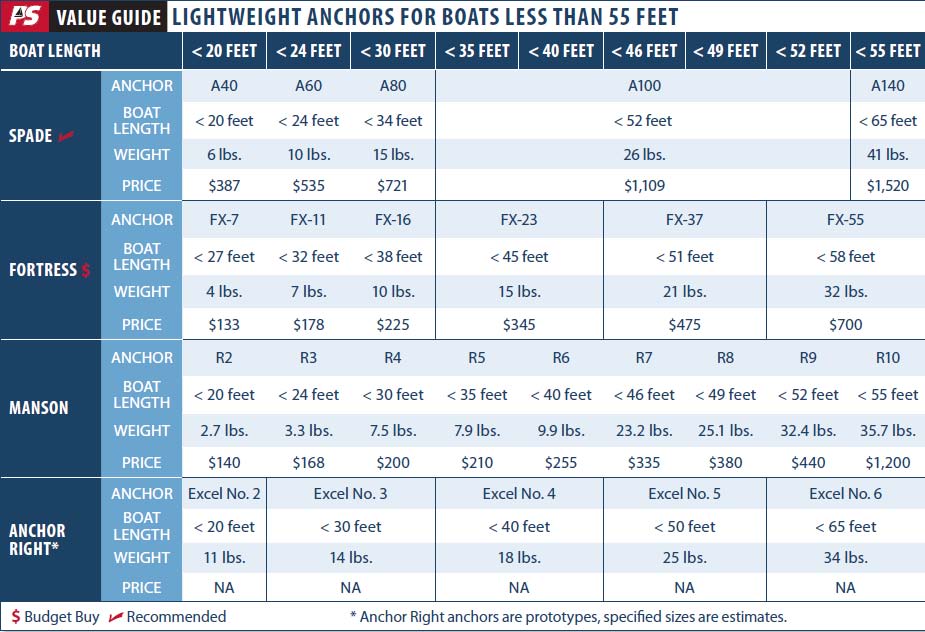

The preference for the Fortress brand has since become institutionalized. In the Volvo Ocean Race, the rules specify that all yachts carry at least two Fortress FX-85s. Although bulkier than other anchors, the Danforth-style anchors can be disassembled for stowage. The Fortresss physical characteristics, as well as the companys staying power, have given the anchor a wide appeal among cruising sailors as well as racers. But with new alloy designs from other manufacturers on the market, we wonder whether the Fortress is still the best choice in the lightweight-anchor market.

THE LIGHTWEIGHT ANCHOR

All anchors are a compromise. Since some anchor types work best in certain bottoms, it is a good idea to carry anchors of different designs. At minimum, a cruising sailboat should carry at least two anchors adequately sized to anchor the boat under most conditions. Four anchors is often the norm on offshore cruising boats-two working anchors (a primary and secondary), one stern anchor or kedge, and one over-sized storm anchor. Cruising boats that sail with six or more full-sized anchors are not uncommon.

So where does a lightweight alloy anchor fit in the hierarchy of cruising anchors? It depends. Aluminum alloy anchors, particularly multi-part anchors, have a number of strikes against them. Lighter anchors take longer to set and are more likely to drag; their shanks are more vulnerable in side-load situations (aluminum alloys can shear when steel will bend); and multi-part anchors like the Fortress and Spade introduce other handicaps. (See The Pros and Cons of the Collapsible Anchor.)

Despite these drawbacks, if Wednesday evening buoy racing is your passion, there’s nothing wrong with an alloy race-day anchor. Owners of heavy-displacement boats with formidable bow rollers should look at high-tensile steel anchors as their primary anchor.

While high-tensile steel is the king of primary anchors, lightweight alloy anchors have two chief advantages-even for cruising sailors. They are portable, and they are easier to deploy by hand from a small boat. This is useful for kedging a boat into deeper water or away from a pier or obstruction. Because alloy anchors are so easily moved around the boat, they don’t need to be stowed on a dedicated bow roller, making them an appealing choice for a third, backup anchor-especially on boats with only one bow roller. Sizing an alloy anchor varies according to its purpose. Generally, the alloy anchor you choose should have similar holding capacity as the boats primary anchor.

WHAT WE TESTED

Surprisingly, the choice for lightweight alloy anchors is limited. Australian manufacturer Anchor Right is re-designing an alloy version of its galvanized Excel; Fortress produces two models, the Fortress and Guardian; Manson Anchors produces its Racer (another Danforth type); and Spade offers an alloy version of its highly regarded convex-fluke anchor. Practical Sailor has reviewed some of these anchors previously (PS, December 2003, October 2006, April 2013, and May 2013), but we have never looked at them as a group.

Anchor Right is a family business based in Melbourne, Australia, that has been fabricating anchors for more than 30 years. The company is best known for its SARCA (sand rock and coral anchor), a convex-fluke design with a roll-bar. In 2006, the company introduced the Excel, a convex anchor with a high-tensile steel shank; three years later, it released the alloy model. Currently, Anchor Right has no formal distribution outside of Australia and New Zealand, although its anchors can be ordered directly.

Fortress Anchors is a Florida-based company focusing entirely on alloy-anchor production. A good share of its business is defense contract work. With more than two decades in the business, Fortress is the oldest manufacturer in this segment of the anchor industry and has sold hundreds of thousands of units. Manson Anchors is a second-generation, family-owned company based in Auckland. It offers a wide range of anchor designs for everything from small runabouts to superyachts. Its most familiar model is the Supreme, a roll-bar, concave anchor available in galvanized and stainless steel.

The Spade anchor was developed in the 1990s by the late French yachtsmen Alain Poiraud. The anchor is now sold by the family-run Sea Tech and Fun (ST&F), which is based in France, but the anchor is built in Tunisia. ST&F makes other anchor designs but is best known for the Spade, which comes in galvanized steel, stainless steel, and alloy. The bigger stainless versions contain some high-tensile stainless steel. Spade anchors are widely available in Europe and the U.S.

HOW WE TESTED

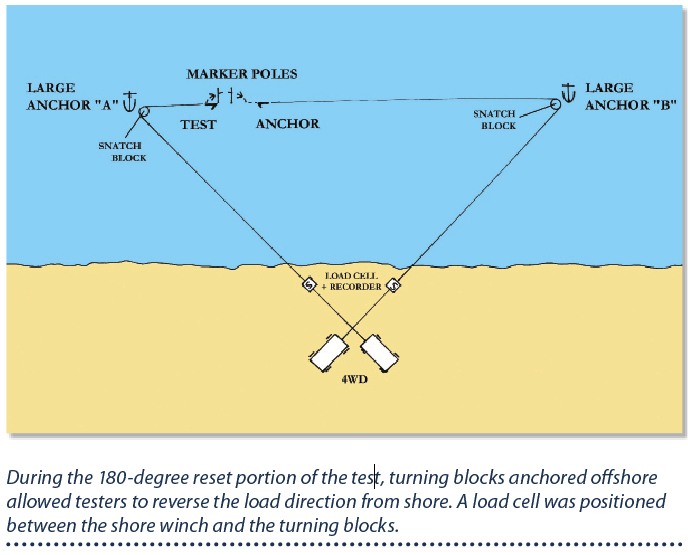

Much of this report is based on the extensive data we collected for our report on anchor resetting ability (PS, February 2013). For that test and this one, we conducted a series of setting, re-setting, and holding-power tests from a beach. We also conducted real-world field tests aboard a 38-foot Lightwave catamaran over a period of several months. (The windage of the Lightwave is comparable to a 45-foot production monohull.)

The alloy anchors tested were the Fortress FX-23, the Spade A80, and the original prototype of the Anchor Right Excel No. 4; each weighed at or under 18 pounds. Although we inspected the Manson Racer, we did not test it; in light of Manson’s recommended uses for the anchor, we would not consider it a contender for use on a cruising boat.

The beach testing was conducted with the anchors under water in the intertidal zone. Test loads were applied using a winch mounted on the front of a four-wheel-drive truck parked on the shore. The online version of this article has links to illustrations depicting the test setup and a more detailed description of the testing. For field testing, the anchors were alternated through use as the primary anchor during an 800-mile, roundtrip cruise from Sydney to Southport, Australia. Testers anchored in six different anchorages with bottoms varying from hard sand to good, clean sand and mud. Some of the anchorages were subject to ocean swells; others were protected. Winds of up to 35 knots were encountered during testing. For rode, the testers used 165 feet of 5/16-inch chain. The Spade A80 and alloy Excel No. 4 were set from the bow roller; the Fortress was deployed by hand because it did not fit on the roller.

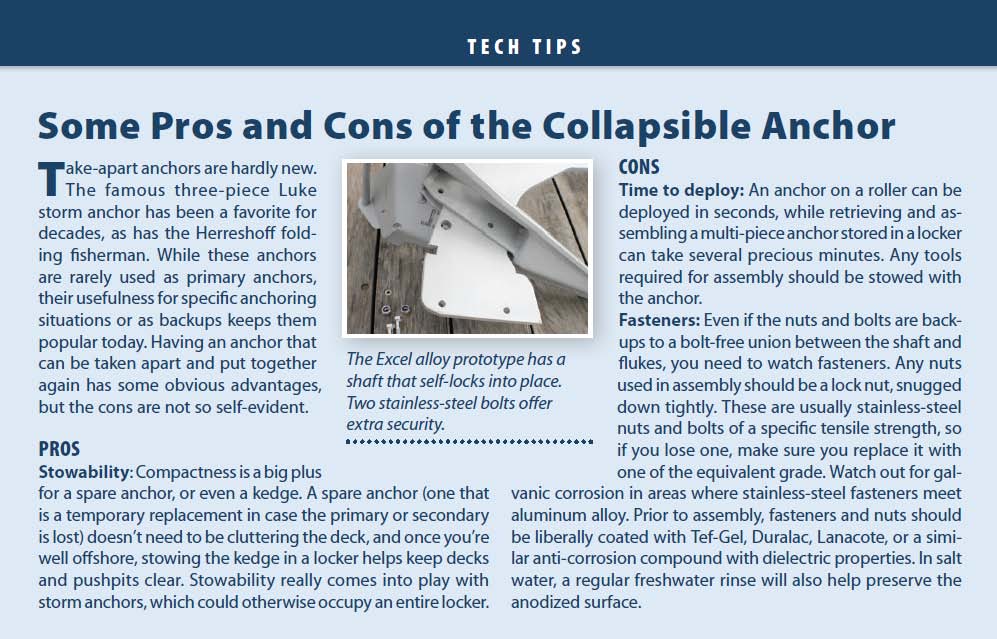

Anchor Right Excel No. 4

The alloy Excel No. 4 is almost identical to the steel version, but the latest incarnation has a removable shank. The anchor shank fits into slots underneath the fluke in a way that the shank can’t pull out. It is possible a model will be introduced with a welded shank, which according to the maker, is less expensive to produce.

The removable shank is secured with two bolts and lock nuts. Unlike the steel Excel, which has a steel-weighted toe, the alloy version is weighted with lead. During previous testing of the anchor shanks, the alloy Excel’s shank bent. Anchor Right has since re- engineered the alloy model, with a detachable shank made from very high-strength 7075 alloy, with a yield stress of 500 megapascals (MPa) versus the 250 MPa of the original 5083 alloy. With the new shank, the alloy Excel is about 50-percent thicker than the high-tensile steel version, and in theory, it should also be stronger.

In both the beach testing and during the extended cruise, testers could not differentiate between the performances of the alloy and galvanized-steel models. Both set quickly, even in light weed bottoms, and both developed sufficient holding capacity. In the veering tests, the alloy Excel turned well and remained set.

Bottom line: The No. 4 appears to be a contender, but may be difficult to source. You can contact Anchor Right Australia for sales inquiries by emailing sales@anchorright.com.au or calling +61 3 5968 5014. They offer both steel and alloy versions

Fortress FX-23

The Fortress anchors, which can be described as Danforth-types, are made from alloy extrusions manufactured specifically for the company, but all of the machining is conducted in-house. All Fortress anchors are sold in a kit form, but we found the assembly instructions easy to follow.

Fortress is specific about its anchor sizing, and this usually results in its recommended sizing being much larger than its competitors, in terms of fluke size. If surface area alone were a measure of holding capacity, then the Fortress would best its peers. Anchors with flukes of such large surface area can make for a good storm anchor, but we would much prefer a high-tensile steel anchor for a storm anchor.

Fortress anchors are designed for everything from the smallest runabout to 300-ton ocean-going vessels. The original model was the Fortress, an anchor that has withstood the test of time. The company’s Guardian anchor lacks the sophistication of the Fortress but offers a less expensive option for lunch-hook conditions. This is what Fortress says of the Guardian: Fortress Anchors are designed for the broadest possible range of applications and seabeds. . . critical applications where failure to set or failure to hold due to varying seabed conditions is unacceptable. . . Guardian Anchors are designed for recreational applications . . . where the boat is being constantly monitored . . .

Fortress anchors are made from 6061-T6 alloy, sometimes known as aircraft aluminium. This alloy grade has a higher yield strength than conventional 5083 marine-grade aluminum. The Fortress FX-23s shank is engineered with a double taper to ensure side loads are spread along the full length of the shank, instead of the weakest portion. The Fortress comes as seven pieces plus retaining clips, nuts, and bolts. Assembly is not something to tackle late at night on a heaving foredeck; some of the pieces are small. Disassembled, the anchor packs very neatly, but even assembled, it can lay relatively flat-either chocked on deck or in a locker. The anchor might not fit on some bow rollers, as the shank and flukes are quite long.

PS tested the Fortress FX-23 in a variety of seabeds, ranging from clay and sand to mud and weed. In each seabed, the anchor set quickly and securely. In anything up to a 90-degree turn, the anchor swiveled but did not pull out. The anchor did not set as deeply as others in our test, but that is not so surprising given its large fluke area (approximately 30 percent larger than the fluke area of a comparable Excel or Spade). Weve heard reports, however, of sailors who have used the Fortress in very strong winds and found that the anchor buried so deeply, it was extremely difficult to retrieve. One solution if using a Fortress (or any deep-setting anchor) in strong winds is to lay a trip line so that the anchor can be pulled out backward.

Fortress has a clear and unambiguous warranty. If a Fortress anchor is damaged, the company will replace the damaged parts without question for the life of the anchor. The Guardian range has the same warranty but for only one year; after that, damaged parts are replaced at cost.

Bottom line: The Fortress has earned its reputation as a reliable lightweight anchor, and its reasonable price earns it our Budget Buy rating.

Manson Racer

The 2009 introduction of the Racer, Mansons only alloy anchor, was born out of an employees need for a lightweight anchor to meet International Sailing Federation (ISAF) safety equipment requirements for competitive racing. The Racer is another Danforth variant, sold only as a welded single unit, and its stunningly presented in electric blue. We found no reviews of this anchor or user history; however, Manson and its distributors suggest it is popular and well received, despite its niche usefulness.

We do not recommend the aluminum Racer anchor as a primary anchor, Manson states. The Racer anchor is only designed for racing yachts or as a stern anchor. For small boats like trailer boats, it could even work as a secondary anchor if necessary.

Under Mansons warranty policy, all anchors are warranted for manufacturer’s defects. The warranty is for life but excludes bending.

Bottom line: We did not test the Racer. Given Manson’s cautionary comments, we see it primarily as a means to comply with racing rules. It may be useful as a possible lunch hook or for keeping the current from sweeping your J/24 backward in a calm.

Spade A80

Spade suggests that an alloy anchor is to be used as a secondary anchor. It should not be used as a primary anchor especially when used with a windlass. Only if there is no windlass and weight on the bow of the boat is an issue, should aluminum anchors be used as the primary anchor. The Spade is a slightly concave, fluke design with 50 percent of the total weight in the tip. The anchor has two parts, fluke and shank. The shank is tapered in two directions for added strength. The shank fits into the fluke with a simple mortice-and-tenon joint. The joint doesn’t take any loads, but it uses a retaining bolt with both lock nut and split pin-a real belt-and-braces approach-to secure the shank to the fluke. The anchor is made from 5083 aluminum alloy, also known as marine-grade aluminum.

Assembled, the anchor is best stored on a bow roller, and it will fit most bow rollers. Disassembled, the two pieces can easily be stored in an anchor locker or in an under-berth locker.

Testers have used the alloy Spade often in a wide range of seabeds, including some so hard that a CQR, Delta, Manson Ray, and Lewmar Claw would not engage. The Spade does not collect mud in soft seabeds like some deep-setting anchors, so it sets well and quickly. It has been reported that the alloy Spade does not set well in hard seabeds, but we have not found this to be the case during field tests. It reset quickly in our 90-degree and 180-degree veer tests.

Spade has an informal warranty position, similar to Anchor Right. The difference is that Spade, in America, formally excludes responsibility for bending, but will consider, on a case-by-case basis, damage that was not caused by irresponsibility or the anchor being undersized. Most complaints are accepted and rectified with a smile at no cost, other than freight, to the consumer.

Bottom line: The Spade is an excellent choice as a lightweight anchor, but it is expensive. We recommend it for cruisers who prefer a concave-style anchor to a Danforth-style, or one that can be easily fitted to a bow roller.

CONCLUSIONS

Given the variability of anchorage bottoms, it is difficult for us to point to one anchor-even within the relatively small category of lightweight alloy anchors-as an overall Best Choice.

In our view, the many drawbacks of an aluminum anchor take it out of the running for a primary, or even secondary, anchor on a cruising boat. We’d much rather trust our security at anchor to high-tensile steel. However, having an anchor ready that even the smallest crew member can deploy alone, can save your bacon, as one experienced cruiser put it. If one small person alone is called on to set an anchor from the dinghy, that 66-pound Bruce won’t do. An alloy anchor could also fill the role of the go-to anchor if the anchor is better suited for its type. The Fortresss oversized flukes, for example, give it good performance in soft sand and mud (though not too soft).

Although the new Excel design looks good on paper and is a near twin to the anchor that did well in our testing (until it bent), we have to reserve final judgement until we get one in our hands. However, if the Excel meets expectations and is sensibly priced, we see no reason why it would not earn a Recommended rating.

Spade’s price could be tough for some buyers to swallow, but its less painful if you spread out the cost over the anchor’s lifetime. It earns our Recommended rating for those cruisers who expect to be frequently using their lightweight anchor in a range of bottoms, as it is more versatile than the Danforth-like design of the Fortress. It is also the better choice for those who would like to keep their anchor mounted on a roller, ready to deploy. We are not big fans of the Spade’s case-by-case warranty policy, which does not afford the confidence we would expect at such a high price.

The Fortresss chief drawback is its size. If you wanted to carry one of these anchors on a bow roller, then the Fortress would not be a first pick. On the positive side, the company has an enviable longevity as a manufacturer and its warranty is excellent. The anchor is available virtually anywhere in North America and is not-compared to its peers-expensive. It stands out as a PS Budget Buy for a lightweight anchor.

This article was first published August 13, 2013 and has been updated.