The 2004 Newport-Bermuda Race was one of the more complex, weather-driven races we’ve sailed in the last 25 years. A combination of low-pressure systems, high-pressure zones, and a late-season cold front of unusual strength presented navigators and tacticians with a difficult challenge. Throw in a tantalizing southerly meander of the Gulf Stream—and a potentially race-killing area of foul current north of Bermuda—and you had a true navigator’s nightmare.

I sailed as navigator and tactician on board Rob Mulderig’s Starr Trail, a 72-foot sloop out of Bermuda. With her Bruce Farr pedigree and four-spreader carbon rig, you might expect Starr Trail to be a flyer, but she’s actually a fully-fitted cruising boat. In fact, the boat recently completed a four-year circumnavigation, fulfilling a dream for her owner.

We’ve raced aboard Starr Trail in venues as diverse as the Caribbean, Thailand, and the English Channel for the America’s Cup Jubilee in 2001. She epitomizes the true modern cruiser/racer, though her 85,000-pound displacement and relatively small sail plan aren’t the best combination for a predominantly light-air race such as this year’s Bermuda Race.

For most boats, the first part of this year’s race featured painfully light air, followed by some 24 hours of strong northerly winds associated with a frontal passage, followed by a dying easterly. Accurate weather forecasting during the race played a key role in determining success or failure.

Weather Access

There was a significant increase in the number of boats using the Internet for weather updates. The rules governing Internet access during racing are evolving at a slightly slower rate than the technology itself. In general, however, access to information on publicly available websites is permitted, while information available from password-protected or subscription-only websites isn’t.

There is a huge amount of really good information available via public sites such as www.opc.ncep.noaa.gov, NOAA’s Ocean Prediction Center website. The problem for sailors is connection speed. In a day when 56K dialup connections on land are archaic, the 9.6K speeds of commonly used satellite systems such as Globalstar are positively Jurassic. With older protocols such as mini-M, Internet access for anything other than simple e-mail is impractical.

Most weather websites are graphics-intensive: it’s simply part of the appeal, and is not an issue with land-based connection speeds. Slow down the access speed dramatically, however, and many programs will stall out.

You simply cannot use web browsers in the same way at sea that you can at home. Instead, it is important to know the exact page address for the information you’re seeking. A lot of research is critical before a race to know exactly what you’ll need while racing.

Ironically, we had trouble downloading weather maps from opc.gov that were identical to the same maps transmitted by conventional weatherfax. Of course, with conventional weatherfax, you have to wait until the maps are transmitted via SSB, while Internet access allows you to grab the maps as soon as they are posted on the website, rather than waiting for a specific broadcast schedule.

You also have to remember that forecasting is still an imprecise science, particularly when it comes to the exact timing of system movements. Yet this is exactly the type of information that is critical in making tactical decisions while racing offshore.

During the 2004 Bermuda Race, a slow-moving, weak, high-pressure system was the major tactical problem for the second half of the race. South and east of the new high, the gradient winds would remain predominantly easterly, weakening toward the center of the system, then strengthening from the southwest after the high passed southward over Bermuda. As the high overtook the fleet, the winds would gradually clock through southeast, south, then southwest as the high merged with the usual summer mid-Atlantic high pressure that normally occupies a large portion of the Atlantic basin south and east of Bermuda.

The question then became: do you hold to the west in anticipation of the clocking breeze as the high passes, or do you go east to try to retain the last of the easterly breeze on the final approach? Complicating the question was a large, somewhat circular area of poorly defined but significant current straddling the rhumbline. The favorable current was east of the rhumbline, the foul current west.

Conventional wisdom for the Bermuda Race says that in the absence of strong evidence to the contrary, you stay west. Any increases in wind velocity are likely to come from systems moving off the east coast of the US and colliding with the mid-Atlantic high, compressing the isobars along the western side of the high. Staying west ordinarily keeps you in stronger winds, and gives you a better angle of approach with any winds that are west of south.

This year, however, following conventional wisdom would potentially place you bow-on to a significant amount of foul current: over two knots in some places, as it turned out. Sailing around the eastern side of the current, however, was a gamble that placed you in the area known as the “Death Zone” to experienced Bermuda Race navigators. In my 18 races to Bermuda over the last 25 years, only once has it paid off to be significantly east of the rhumbline during the last 200 miles of the race.

Aboard Starr Trail, strategy was dictated by the need to keep this heavy boat sailing at its fastest possible wind angle at all times, particularly in a dying breeze. With the remains of the northeasterly gradient clocking slowly, we sailed southeasterly across the top of the current feature, following the wind direction as it slowly headed us and diminished, changing from heavy spinnaker, to light spinnaker, to headsails.

The slowly clocking wind was not a good sign. If it continued to veer, boats on or east of the rhumbline could be caught in a dead beat to the finish in light air, while boats to the west brought down the new breeze.

We elected not to foot to the anticipated new breeze, and instead held high, hanging as far to the left as possible while staying marginally cracked off to keep the big boat moving in decreasing winds.

This was not a blind call. The key to this strategy was a modern version of one of weather forecasting’s oldest and most reliable tools: the barometer.

While the rate of motion of weather systems is not easy to predict accurately, the actual pressure gradient within the system is well-known. Watching the barometer, and recording its rate of change, will tell you with remarkable precision just how quickly a weather feature is approaching.

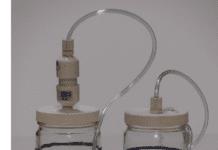

Changes in barometric pressure over time are most easily tracked using a recording barometer, or barograph. The traditional barograph looks much as it has for the last 150 years or so, with an ink pin connected via a linkage to an aneroid system. The ink pin draws a line on a calibrated paper chart mounted on a clockwork-driven rotating drum, giving you a trace of pressure against time.

The traditional barograph works well, but the pen even on marine-damped versions can jump around dramatically in a heavy sea. A simple barometer does a good job, but it requires discipline to record and plot changes in pressure, and does not so easily show rates of change.

Modern performance instrument systems such as those from Ockam can add an integral atmospheric pressure sensor, and electronic strip charts to record pressure against time on the computer, just like a traditional barograph.

For those without integrated instrument systems, self-contained electronic barographs have been the answer. The German-made Meteoliner, formerly marketed by Vetus, has been the standard electronic barograph for offshore racing since its introduction, but we can find no source for it today. It was not cheap at around $800, but it is worth its weight in gold to those of us who race offshore. This is what we had aboard Starr Trail.

An intriguing new electronic barograph is the Meteograf, marketed in the US by Robert E. White Instruments, one of the country’s premier dealers in weather instrumentation for mariners. The Swiss-made Meteograf is in some ways a cross between a traditional barograph and a modern electronic baroscope. Its electronic pressure sensor is not affected by the boat’s motion, and its compact flush mount fits easily into a bulkhead.

A digital readout shows real-time pressure, and a scaled paper chart records pressure over time like a traditional barograph. The waxed paper chart is etched by a stylus rather than a pen, and a single chart is good for a year, unlike conventional barographs that require a weekly paper-changing ritual. You can also connect the Meteograf directly to your computer to record pressure over time in permanent electronic fashion. At about $1000, this is a serious tool for serious, weather-oriented sailors.

And how did a barograph help us in our strategic call? The key was the rate of change of the pressure, as well as its absolute value.

The central pressure of the new high was about 1020 millibars. When our pressure, which had been slowly increasing as expected, dipped from 1016 to 1015 (adjusted for diurnal variation), and stayed there with little tendency to rise, it seemed likely that the new high had slowed down somewhat, and the old gradient would prevail.

The easterly breeze—a notoriously unstable breeze around Bermuda—wavered and oscillated, but ultimately held until we crossed the finish line. Those to our west died, and those to our east gained.

Internet weather is great, weather charts are extremely important, but ultimately, one of the oldest weather forecasting tools for sailors was the most critical part of our weather-driven strategy this year.

Jibe-Ho!

Jibing any sailboat in heavy air is no picnic. Strategy and weather in the 2004 Bermuda Race dictated a jibe in the middle of the night in the Gulf Stream for the faster boats, and the result in some cases was a surprising amount of damage.

Aboard Starr Trail, we were running as deep as possible to position ourselves properly—virtually dead downwind after the frontal passage in winds averaging almost 30 knots, gusting into the high 30s—when the time came to jibe to port down the axis of the Gulf Stream. Our boatspeed was averaging about 13 knots, but surging regularly into the high teens with the gusts.

Speed through the water peaked at 21.8 knots, and we had several knots of positive current. It’s not often you see 24 knots over the bottom in a displacement sailboat, even if it’s only for a few seconds. This, mind you, is in a 43-ton boat, not some lightweight flyer.

It happened to be about 0330 in the morning, and pitch black—not the easiest of conditions for a jibe. Even in daytime, it would not have been a simple job.

During the jibe, the helmsman, who is an Olympic-caliber sailor, lost track of his position relative to the wind—easy to do in total darkness, with only the instruments to rely on—and crash-jibed the boat twice after the initial, more controlled maneuver. It is no joke when a 1,200-square-foot mainsail on a 27-foot boom comes whistling over your head, out of control. Luckily, no one was injured, although the stops on the mainsail track were damaged.

Other boats were less fortunate. The steering pedestal guard on one boat—and with it the compass and other electronics—was demolished during a similar maneuver. Even with pedestal guards that are tapered and supposedly snag-proof, the load of a mainsheet bearing against the guard before freeing itself can do a lot of damage in a very short period of time.

Whether racing or cruising, jibing any boat in heavy weather requires careful coordination between helmsman and sail trimmers. The mainsail should be trimmed in hard amidships (easing pressure on the preventer as you trim), before turning the boat through dead downwind. The preventer should be led to the boom from the new leeward side before easing the boom out on the new jibe, and must be taken up as the mainsheet is eased. “Total control” should be the operative phrase.

If you don’t have a main boom preventer rigged any time you are more than about 70 degrees off the true wind, go directly to jail, do not pass Go, and do not collect $200.

Of course the spinnaker and pole are being jibed at the same time as the mainsail, so things can get pretty busy on a racing boat, where the primary goal is to keep the spinnaker flying and the boat moving at top speed. The relatively “easy” job of jibing the main sometimes gets lost in the shuffle until something dramatic occurs.

Most boats lack sufficient mainsheet winch speed to trim the sail hard in at a rate that suits the helmsman during a jibe, so the boom comes crashing over when partially trimmed. This may work inshore in flat water, but we do not recommend it when sailing offshore in heavy air, especially at night.

Aboard Calypso during our circumnavigation, Maryann and I developed a more or less idiot-proof jibing procedure that bears repeating. We used this in winds up to 35 knots or so, generally running with a headsail on the pole rather than a spinnaker.

First, roll up the headsail (assuming it is roller-furling) by easing the pole forward as you grind in the furling line. With the headsail furled, leave everything under tension in the foretriangle—foreguy, topping lift, and sheet—until the main is jibed, so the pole can’t bang around.

I would then go forward to the rail to control the preventer using its four-part purchase. Maryann—all 100 pounds of her—would overhaul the mainsheet using only its 6:1/24:1 multi-speed tackle, which in a strong breeze, was just powerful enough for the job.

To jibe the main, ease the preventer while trimming the main in hard amidships. This requires constant communication, and, depending on the location of the mainsheet and preventer controls, is often a two-person job. On our boat, we then transferred the primary preventer tackle to the new leeward side, leaving it attached to the boom during the maneuver.

Needless to say, both of us were wearing safety harnesses during this process, as the chance of recovery if one of us went overboard was close to zero.

When we say “trim the main hard amidships,” we aren’t joking. That means zero slack, so that the main is virtually completely stalled. The boat will slow down, but should still have plenty of way on if you do the maneuver reasonably efficiently.

We generally brought the boat onto the new course by bumping the autopilot five degrees at a time until the top of the main filled on the new jibe. The rest of the mainsail quickly follows the top across, which is the point at which things can turn to custard in heavy air if the boom isn’t under complete control, as the boat will tend to heel hard over and round up.

We would then over-compensate to the new course, reaching up slightly, just to make sure that a re-jibe was unlikely. At this point, the main is slowly eased against the preventer, which is taken up at the same rate.

With the main nailed down on the new jibe, the secondary preventer is hooked up, and the new weather running backstays taken back into position. The boat is snuck down to the proper course, once again easing the main while taking up on the preventer.

Note that the preventer will only keep the boom under control if it has a reasonable pulling angle. A preventer led to the bow from the outboard end of the boom is pretty much useless once the boom nears amidships.

Our primary preventer would have been called a vang in older times, as it consisted of a heavy four-part tackle attached to the boom halfway along its length, led to the rail. With the boom eased off, the pull of the preventer was pretty much down as well as forward, and the load on everything was considerable, even with only 400 square feet of mainsail. The boom, preventer tackle, and points of attachment all need to be up to the job for this arrangement to be practical.

The secondary preventer was what is more normally considered a preventer—a line led from the end of the boom to the bow. Both types of preventer are essential on a cruising boat running downwind during offshore passages.

Because of Calypso’s fixed inner forestay and over-length spinnaker pole, jibing the gear in the foretriangle and re-setting the headsail takes longer than jibing the main, but unless I did something stupid—which happened on several occasions—there was little risk of damage to the boat or crew.

Mind you, this two-person jibe procedure is too time-consuming for the average offshore racer, but here’s a lesson to take to heart. During the Bermuda Race, a number of crews facing this same heavy-air jibe chose to take down their spinnaker, jibe the main and pole, then re-set the spinnaker on the new jibe. Several boats took this opportunity to change down to smaller spinnakers, which proved to be the right call.

Aboard Starr Trail, we decided to jibe the 1.5-ounce spinnaker and the main simultaneously, which in retrospect was the wrong call. A half hour later, the hard-pressed 1.5-ounce chute decided it had had enough, and God called for a spinnaker change. The log records laconically: “blew out 1.5, set 2.2.”

Conclusions

Starr Trail didn’t win this year’s Newport-Bermuda Race, but our 11th-place finish overall out of over 100 boats in the IMS cruiser/racer division was an excellent performance in conditions that clearly favored lighter, more modern boats. In fact, the boats that beat us on corrected time—three new Swan 45s, a J/125, a pair of Santa Cruz 52s, and several purpose-built lightweight cruiser/racers—all had significant advantages in the light air that characterized most of the race.

We beat all the more “traditional” maxis and mini-maxis on both elapsed and corrected time.

If there’s such a thing as a moral victory—and it’s not as sweet as holding the winner’s trophy, I assure you—we scored one, thanks to a hardworking crew, a well-prepared boat, and more than a little bit of good fortune. It’s just the type of finish that keeps you coming back for more, year after year.