Anyone who has been on the bitter end of the sheet when a big genoa starts to fill—whipping and shaking with terrifying violence—knows how important it is to have a winch to convert that flailing energy to forward propulsion.

Winches are to sailboats what the inclined plane was to the Egyptians.

They make the difficult easy, place the impossible within reach.

The equivalent of a dozen or more men needed to heave on a square rigger’s halyard or brace is represented on a modern sailboat by a small, precision-made, cylindrical machine packed with levers and gears.

The refinement of gearing and the development of smooth-operating self-tailers has promoted modern winches from two-man to one-man workhorses with amazing power.

Their only negative is their proclivity to induce fidgety idlers to rotate them mindlessly, just to hear the pawls ratchet. These idlers usually can be broken of this annoying habit by shouting, “Winchclicker! Winchclicker!! Winchclicker!!!” If that fails, they generally are put ashore (if in harbor) or put to death (if on a long sea voyage).

Let’s take a close look at two common sizes of winches. They’re all expensive, because they are well-made precision equipment. They’re also among the most frequently retrofitted items; it’s worth repeating here that an oft-heard saying aboard a lot of sailboats is that the winches they came with are not big enough.

In the two categories selected, these winches are from six manufacturers—Andersen (Denmark), Antal (Italy), Barton (England), Harken (United States), Lewmar (England) and Setamar (Germany).

Small Winches

The first category is very small winches. Those represented in this evaluation are among the smallest made by five of the manufacturers. One maker, Antal, makes excellent small winches in several sizes, but could not supply one for testing.

Small, single-speed winches, either with a handle or simply snubbing winches, are invaluable on small boats, for halyards, jib sheets, spinnaker sheets, reefing gear, vangs, etc., and handy, too, for many tasks aboard larger boats. Small winches do not come with the self-tailing mechanism; most manufacturers (Andersen is the exception) start the self-tailers with #16s, which also happens to be the minimum size for two-speed gearing.

Small winches are said to have a gear ratio of 1:1. That means they are direct drive. The only power advantage is that provided by a winch handle. It’s simple leverage, with two sets of pawls (one pair to restrain the drum; the other pair to permit the handle to ratchet freely). One turn of the crank is one turn on the drum. On a small boat, the single-digit power ratio provided by the handle often is ample for sheets. Non-geared winches take in line rapidly. Such winches often are used for halyards on somewhat larger boats. (The power ratio is the length of the handle divided by the radius of the drum.)

Snubbing winches, which do not accept a handle, turn in one direction only. They need only a single set of ratchet pawls. If enough wraps are applied, snubbing winches give the user time to get a new grip or to simply hold the line lightly while friction between the drum and the line takes the load.

They provide little mechanical advantage, but snubbing winches facilitate a good utilization of intermittent muscle power, They also have good line retrieval speed, which always is a consideration when dealing with winches.

Simple and trouble-free, they are of great value when the line load is no more than one’s weight or pulling strength. A halyard can be sweated up very taut by the “heave and hold” method of pulling hard on the line perpendicular to the mast with one hand while grabbing slack on the winch with the other hand.

With either small, direct-drive winches with handles or simple snubbers, the line retrieval rate is an undiluted derivative of the drum diameter, i.e. one revolution of the winch hauls in a length of line equal to the drum’s diameter multiplied by that popular symbolic 16th letter in the Greek alphabet. As a practical matter, line in equals line out.

Because they are simple devices, these small winches were not tested.

The Roaring 40s

The second category is the very popular “Number Forties.” Winches are given numbers that correspond to their lowest and most powerful gear ratio. The power ratio of a geared winch is the length of the handle divided by the radius of the drum, multiplied by the gear ratio.

The big winches in this test are Andersens, Antals, Bartons, Harkens, Lewmars and Setamars. We tried to include the Australian-made Murray bottom-action winches, but could not find a U.S. distributor.

The versatile #40s—or their close equivalents—serve as genoa sheet winches on 30- to 35-foot boats, for spinnaker sheets and mainsheets on boats up to 48′, and for halyards, topping lifts, vangs, etc., on much larger sailboats.

The #40s in this collection are all two-speed. Three-speed winches usually are found on racing boats; they come in bigger sizes and get complicated and expensive.

All but one of these winches are self-tailing. In the beginning, several decades ago, self-tailing winches were troublesome…as is usual with most new things. Now perfected, the self-tailing mechanisms represent the only way to go on either racing or cruising boats.

Because winches are such beautifully made gear and rarely get worn out, marine consignment shops across the country are clogged with standard winches—mostly Barients—that once were highly coveted (as well as highly priced). We know of at least one instance in which dozens of perfectly usable standard winches were sold as scrap metal.

There even are a few early-model self-tailers (from various manufacturers) showing up now in the consignment shops; they’re okay for moderate duty but, generally speaking, are not good buys because the self-tailing mechanisms often are not as refined as those on current models. In plain English, that means they slip under heavier loads. Many also have abrasive drum surfaces that devour line.

The Test

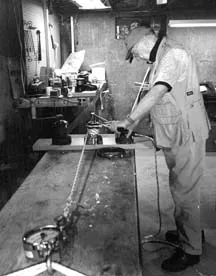

The Practical Sailor test, designed to establish efficiency ratings for winches, involves mounting each winch on the workbench.

To measure the force exerted, a 15″ torque wrench was used instead of a standard 10″ handle. (The extra length of the torque wrench required adjustments in the calculations.)

Sta-Set X, a modern, rather slippery line, was used, with some of the early tests repeated using Regatta braid, a fuzzy-finish line. The theory that because of varying friction a slippery line might produce different numbers than a fuzzy line proved specious.

At the other end of the bench, a tripled length of 1/2″ shock cord held by two eye straps provided the resistance. Shackled to the shock cord was a carefully calibrated Dillon dynamometer with a handy red max needle. The Sta-Set was attached to the other shackle on the dynamometer and thence to the winch. Four wraps were used. A minimum of three generally is recommended for all but extreme loads. The exception was the Setamar, which requires just one partial wrap of at least 220°.

Pulls of 10 and 20 pounds were for the trimmer easy work. Additional pulls of 30 pounds produced some sweat. A pull of 40 pounds probably would be regarded by an average person as a maximum effort; 50 pounds would be something only a bench-pressing girlfriend would do without making some kind of noise.

The numerous pulls produced figures whose averages indicate how close each winch came to meeting its power ratio.

An additional step in the testing was to determine how easy it is to free the line from the self-tailer and ease the line, as one would do in easing a sheet or halyard when coming off a beat onto a reach or run. In the case of the Setamar, this becomes complicated and is controlled by the handle.

The Results

First of all, the fact that the smooth-skinned Sta-Set performed the same as fuzzy Regatta braid indicates that the gripping action of the self-tailing mechanisms on all of these winches probably is no longer at issue. There were difficulties when self-tailers were first introduced; that was before it was recognized that the diameter of the drum and the base diameter of the self-tailer were very critical dimensions.

Click here to view the Winches Value Guide.

There appeared to be no slippage. However, the sharpness of the teeth on the self-tailers’ disks may well affect wear on the line.

Dealing first with the small winches, there are lots of places on small boats where the ultra-simple Barton snubbing winch (about $50) would be useful. The almost equally simple Lewmar #6 ($92 in anodized aluminum) has an efficient mechanism; it also comes (for more money) in chromed or polished bronze. The #6 Harken ($108 for aluminum) turns on sleeved bearings and is the smoothest operating.

For small-boat sheets or bigger-boat halyards and vangs, the small single-speed Setamar ($364) makes eminently good sense. The ability to ease a sheet or halyard by turning the handle in the opposite direction, before freeing the line entirely, constitutes, in our opinion, a valuable safety factor. As was pointed out in an earlier, more detailed review (in the February 15, 1997 issue), the drum-less Setamar winches are very ingenious and may represent the design approach of the future. However, they currently are too expensive.

The Andersen #6 ($102), all-stainless, beautifully made, with Andersen’s ribbed drum and needle bearings, commands categorization as top-of-the-heap and Best Buy.

Summarizing now about the large winches, it’s tough to choose between Andersen and Lewmar. But first, let’s review the others.

The little Barton G23 is not comparable with the big 40s. It was included not only because it’s Barton’s biggest winch, but also because it may point to the future. An “Ugly Ducking”, if there ever was one (see photo), the Barton is made largely of reinforced plastic (including plastic needle bearing), but with a stainless steel axle, pawls and planetary drive gears made of sintered stainless, and a stainless sleeve on the plastic drum. The winch is a powerhouse and, along with being very light and corrosion free, requires almost no service. An occasional flushing with an optional light hit of WD40 is all it needs. It’s a $400 workhorse.

Although handsome winches and very finely made, both the Harken and Antal suffer from what appear to be unnecessarily complicated innards that produce some fall-off in efficiency. They suffer especially in their geared high speed modes and make the initial retrieval of line quite slow compared with the Setamar, Andersen and even the Lewmar.

In addition, the Practical Sailor tests revealed that the Harken drum surface caused abrasion on the Sta-Set line that was easily detected visually after only three or four “pulls.” The Harken and Antal have the most abrasive drums.

The Setamar? It’s so different, it’s difficult to compare with the more conventional #40s. It has a number of strong points. The principal ones are that it retrieves line fast (as fast as the Andersen) and easing of a loaded line can be controlled very safely with the handle (after shifting the top ring). Other benefits are that no wraps are needed; it is small and very lightweight, and line wear is the lowest of all.

The Setamar negatives: It is not a thing of beauty; is complicated to strip and clean (which it requires often); takes some “getting used to,” and it is far too costly.

Both the best and the Best Buy is the Andersen, but there’s almost no gap between it and the Lewmar.

The Lewmar, a first-rate value, is part of a line that was completely redesigned a few years ago to simplify the gearing, reduce the number of parts and make the winch both stronger and easier to service.

The Lewmar ranks first in efficiency, a hair ahead of the Andersen, and is easy to disassemble. If it had a drum as good as the Andersen, it would be a toss-up.

The Andersen has a direct drive high gear that retrieves line fast, a good low gear mechanism that may come second to the bearing-packed Harken, but its real forte is the polished stainless steel drum. The drum, a masterpiece of metal-working, is ribbed, which produces very little abrasion because it moves the coiled line up the drum much better than an abrasive drum. The drum should last virtually forever.

A peculiarity of the Andersen is that when the line is heavily loaded, easing the line can be a bit jerky as the line skips from rib to rib. Although initially disconcerting, it is not even a minor problem.

There’s nothing second-rate about any of these winches. They all work very, very well and last a long time if properly cared for. The choice may involve gear ratios, serviceability or even cosmetics (we still believe a good part of a sailboat’s appeal is aesthetic).

If it’s something different you want, try Setamar. If you don’t need a large winch, don’t overlook the “new-tech” Bartons. But for efficiency, serviceability, construction and appearance, our top choice is the Andersen.

Contacts-

Andersen, Scandvik, Inc., 423 4th Pl. SW, Vero Beach, FL 32961-0068; 561/567-2877. Antal, Euro Marine Trading, Inc., 62 Halsey, Newport, RI 02840; 800/222-7712. Barton, Imtra Corp., 30 Samuel Barnet Blvd., New Bedford, MA 02745; 5008/005-7000, www.imtra.com. Harken, 1252 E. Wisconsin, Pewaukee, WI 53072; 262/691-3320; www.harken.com. Lewmar, New Whitfield St., Guilford, CT 06437; 203/458-6200; www.lewmar.com. Setamar, Setamar USA, Box 840, 17 Burnside St., Bristol, RI 02809; 401/253-2244.