The Escoffier rescue was both a success story and a good lesson about decision making in extremis. Right from the start Kevin settled on a sensible set of priorities, sidelining damage control in favor of abandoning ship. Even though PRB was disintegrating around him, he transmitted a Mayday message and ensured that his EPIRB had auto-activated. He knew he had only a few fleeting minutes to don his survival suit, ready his life raft, and gather what he could prior to abandoning ship. The decision to write off the grab bag was a tough call, but getting the raft launched, boarding, and clearing the rigging mine field were even important priorities.

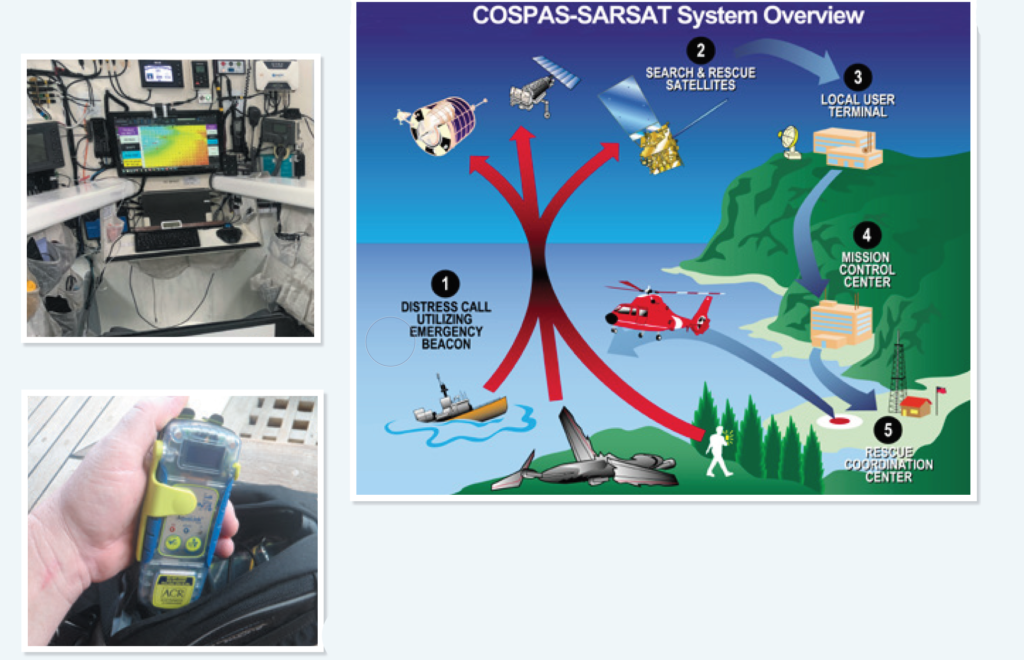

A key factor in the success of Escoffier’s rescue by another solo sailor is the role played by a team of shore side experts. The first to engage was Vendée Globe’s “Race Direction”, who acted as a virtual crew, guiding fellow sailor Jean Le Cam to Escoffier’s life raft. This support in finding the needle in a haystack and guiding the rescuer to that location tested both communication equipment and the position finding capability of the COSPAS/SARSAT system.

There’s both a bit of irony and a lot of common sense involved in this rescue. The irony lies in the fact that when solo sailing goes awry, it takes a village, a sky full of satellites and the well proven effectiveness of GMDSS to affect a rescue. In this case, shore-based responders became a de-facto part of the crew. And as with many sea going disasters, the onset was lightning fast, but the following 11 hours seemed an eternity.

The 406 EPIRB signal was received by CROSS Griz Nez in France who alerted Vendée Globe headquarters. They electronically scanned the fleet and saw that Jean Le Cam was the closest competitor. He changed course to rendezvous with Escoffier and his life raft.

This was a collaborative rescue and every major ocean race organizing committee should take note of how it unfolded. The international GMDSS system relayed location information to Race Direction because the French RCC and the Vendée Globe Race had previously agreed on this approach. Race Direction took on the role of primary rescue coordinator and implemented its plan to divert other competitors to the location of the vessel in distress—in this case, a competitor in a life raft.

The upside in this approach is multifaceted. It puts those who have the best understanding of sailors and sailboats in a particular event in a pivotal role. If they have an effective communications system and other competitors in the area such an approach makes sense. In cases where such organization is not an option, or where coastal SAR organization such as the US Coast Guard are available, the latter will become lead agent in the rescue effort.

Not only did Race Direction take the lead in this well executed rescue effort, but it became a real time collaborative effort among oceanographers at France’s MOTHY calculating Escoffier’s life raft’s set and drift and search patterns and RCC’s in France and South Africa. All was expedited by excellent satellite communications between vessels and rescue coordinators separated by thousands of miles.

Long term, life raft survival sagas have been greatly reduced thanks to the COSPAS/SARSAT beacon response system.