If we are trying to climb to windward, it’s nice to get as much lift out of the rudder as practical, before drag becomes too great or before it begins to stall with normal steering adjustments. If the boat has an efficient keel and the leeway angle is only a few degrees, the rudder can beneficially operate at a 4-6 degree angle. The total angle of attack for the rudder will be less than 10 degrees, drag will be low, and pointing will benefit from the added lift. If the boat is a higher leeway design—shoal draft keels and cruising catamarans come to mind—then the rudder angle must stay relatively low to avoid the total angle (leeway + rudder angle) of the rudder from exceeding 10 degrees. That said, boats with truly inefficient keels but large rudders (catamarans have two—they both count if it is not a hull-flying design) can sometimes benefit from total angles slightly greater than 10 degrees—they need lift anywhere they can get it.

How can you monitor the rudder angle? If the boat is tiller steered, the tiller will be about 0.6 inches off center for every degree or rudder angle, for every 3 feet of tiller length. In other words, the 36-inch tiller should not be more than about 2 inches off the center line. If the boat is wheel steered, next time the boat is out of the water, measure the rudder angle with the wheel hard over. Count the number of turns of the wheel it takes to move the rudder from centered to rudder hard over, and measure the wheel diameter. Mark the top of the rim of the wheel when the boat is traveling straight, preferably coasting without current and no sails or engine to create leeway.

The rim of the wheel will move (diameter x 3.146 x number of turns)/(degrees rudder angle at hard over) for each degree of rudder angle. Keep this in the range of 2-6 degrees when hard on the wind, as appropriate to your boat. It will typically be on the order of 4-10 inches at the steering wheel rim. A ring of tape at 6 degrees can help.

How do we minimize rudder angle while maintaining a straight course? Trimming the jib in little tighter or letting the mainsheet or traveler out a little will reduce pressure on the rudder and reduce the angle. Some boats actually sail to weather faster and higher, and with better rudder angles, by lowering the traveler a few inches below the center line.

On the other hand, tightening the mainsheet and bringing the traveler up, even slightly above the center line on some boats, will increase the pressure and lift.

Much depends on the course, the sails set, the rig, the position of the keel, the wind, and the sea state. Ultimately, some combination of small adjustments should bring the rudder angle into the appropriate range. Too much rudder angle and you are just fighting yourself.

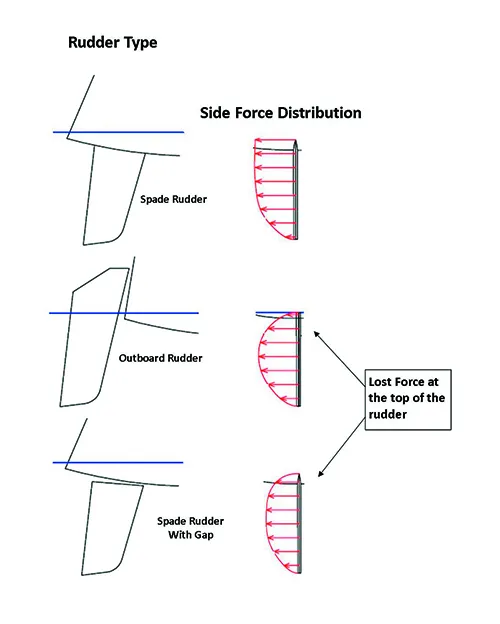

- Turn this rudder just 10 degrees and the end plate is lost, reducing the amount of lift generated.

- This rudder might as well be transom hung, the way that the end cap just disappears.

- Stern-hung rudders, and spade rudders with large gaps between the hull and the top of the rudder will lose their lift at the “tip” of the blade near the surface.