Abrasion

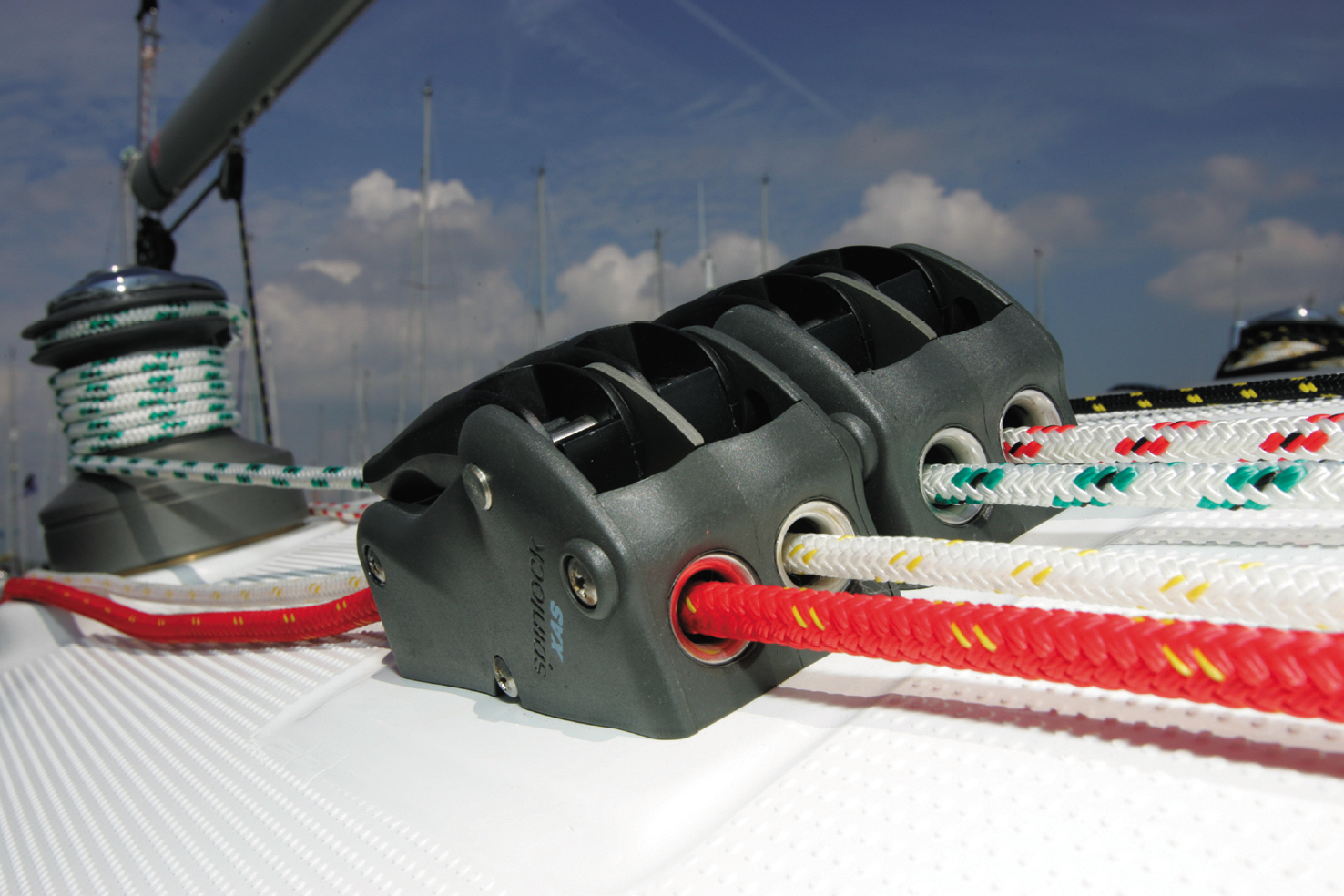

Every time a rope rubs against something there is wear, and a diligent sailor is constantly inspecting his lines for chafe. A rough surface is obvious enough, but even smooth surfaces can do damage over time if there is enough pressure. Reduce the turning angle by improving alignment and reducing bends. Reduce movement using low-stretch lines and by moving the anchor point closer to the bend. Make sure tackles are not twisted and lines don’t rub. Mooring lines should not cross, even right at the cleat. Rope clutches and jammers are common sources of abrasion. Don’t release jammers under load—take the pressure off the line with a winch first. Smooth any rough edges and protect ropes with anti-abrasion coatings (“Chafe Protection for Fiber Rodes,” November 2019) or chafe sleeves (“UV, Chafe Protection,” March 2015). Some authorities say the loss in strength is roughly proportional to the cross sectional area lost, but PS testing has shown that is only true for overall wear, not localized damage. Polyester ropes can actually get fatter as they grow fuzzy, and high modulus ropes can lose strength three times faster than the loss in area suggests, depending on the pattern and how many strands are affected; the slippery, non-stretch fibers do not share loads well.

DISTORTION

Double braid ropes can fail inside, hidden from view. Rock climbers attentively slide their fingers along the rope every time they coil it, feeling for the telltale dents and bumps that signal internal damage. Hard loading over a sharp bend, such as a chock or knot, are common causes.

STIFFNESS

Any rope that seems considerably stiffer than normal, specifically in isolated areas, should be suspected of severe overload or excessive external friction, which resulted in fibers fusing together. The exception is UHMWPE (Amsteel), which can become stiff due to bedding. If the rope does not become supple with a little gentle handling, it is damaged. Alternatively, extreme stiffening could be due to severe UV damage and lime scale accumulation inside the core—same result, the rope is done in.

DISCOLORATION

Is it dirt or mildew? These are generally harmless with synthetics, but wash it off to be sure. Exposed to battery acid? Nylon is totally ruined, since the damage is probably worse on the inside where it lingered. A few drops of paint or a brush mark? Generally harmless, though we mark lines with water-based paint to reduce the risk. Sharpie has been documented to have some minor effect on nylon, but any relationship to actual rope failure is doubted by most testers.

UV DAMAGE

Look for fibers that shed when rubbed with your fingernail. Although the conventional wisdom is that the cover bears the brunt of the damage, we’ve found that with lighter colors the damage can go clear through a 3/8-inch line. The portion of a halyard that lives inside the mast is likely fine, while the bit near the masthead may be severely degraded by UV and chafe.

GLAZING

A line that is heavily loaded while running across even a smooth bend can be externally heated enough by friction to melt on the surface, losing much of its strength on that side. This is common with docklines, occasionally seen on snubbers (see photo page 16). Even rodes can do this, particularly if the anchor roller is jammed. Internal damage is also common, sometimes observable as a lumpiness or stiffness. The broken Kevlar core of the rope in the adjacent photo is indicated by the necking and pliability at the break.

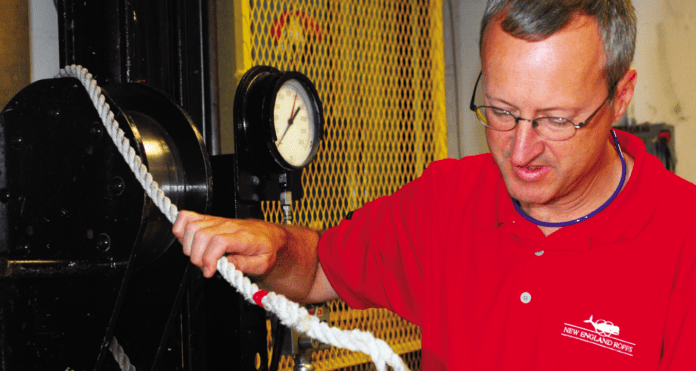

WASHING ROPES

Machine washing a rope in the first 1-2 years for cosmetic reasons commonly does more harm than good. Instead, wash it on the deck with a brush or in a bucket when you wash the boat. Water will remove the sea salt. Over the years, however, ropes can become stiff from loss of spinning lubes, internal wear, and accumulation of lime scale within the core. The sea salt evaporates leaving behind lime, which rain has difficulty removing. Laundry detergents have chelating agents that help remove lime build up, as does the steady kneading motion, but you can restoring internal lubricants (see “What’s the Best Way to Clean Marine Rope?” PS July 2011 and “Aftermarket Cordage Treatments,” PS December 2011).

ANCHOR RODES & DOCKLINES

Renew splices when they appear worn, or when the thimbles or chain they connect to appear corroded. Trimming the ends back liberally as needed; remove the first 5-10 feet every few years is common, so allow for that when you buy the rode. End-for-ending is another common practice.

Docklines are constantly cycling during use, so they are often much weaker than we think. The ropes broken during our test of old lines broke at 1/3 their rated strength.

The Arborists Rope Manual produced by Samson Ropes offers helpful guidance on judging the condition of rope. You can find it at this link: https://www.samsonrope.com/resources/arborist/rope-manual