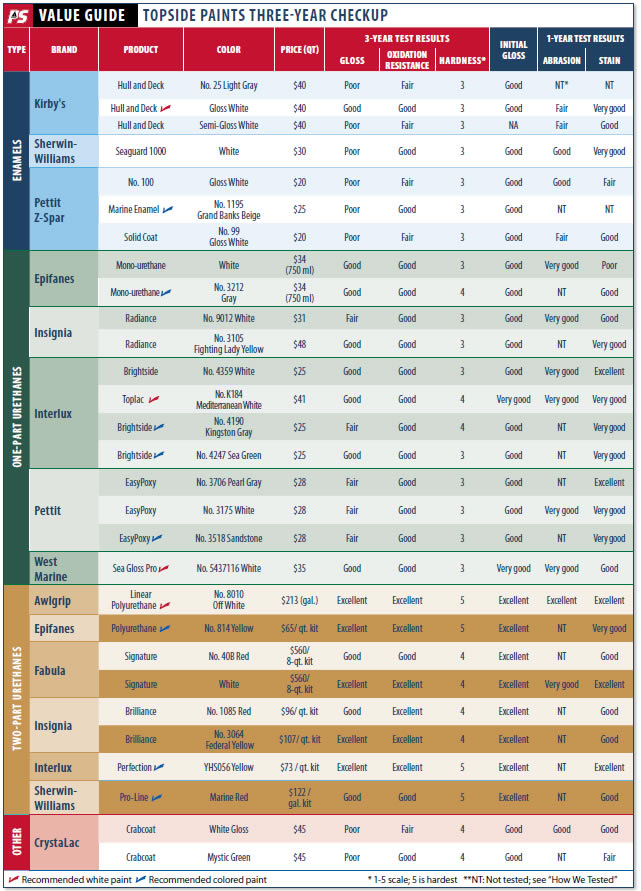

Our topside-paint test panels have endured three full years of 24/7 exposure to the elements, and the time has come for their final evaluation. Testers have annually scrutinized the paint swatches and rated the topside coatings on gloss retention, flow out, scratch resistance, and anti-oxidation ability. In this final round of evaluating, we will also compare the panel results with the products real-world performances aboard our test boats.

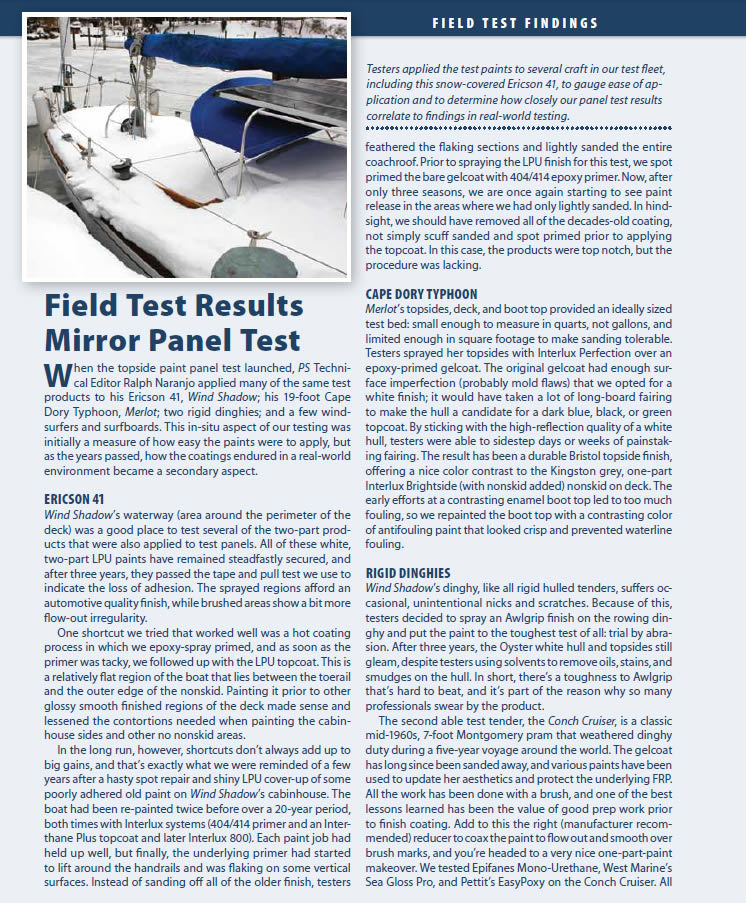

Our goal from the start of this test was to take a variety of promising topside coatings and apply them to boats in our test fleet-sailboats, dinghies, and other craft-and set up an in-situ test to validate or contradict our panel testing. These field tests have put paint systems through more realistic punishment in a true working environment. And the comparison between real world usage and static testing helped us validate both a wide range of the paints tested and the testing protocol itself. (See Field Test Findings” on right)

Testers reported on the application of these paints in the August 2008 issue and rated their performance in the November 2009 and February 2011 issues. Now, at the three-year mark, testers can offer some interesting observations about specific paints and paint types.

How We Tested

For the long-term evaluations panel test, we applied two coats of each paint to carefully prepped sections of fiberglass panels. The panels endured identical weathering, and the swatches were washed with a mild soap before inspection. All ratings are relative to the field.

Gloss-retention testing included taking reflected light readings, in bright daylight, with a spot meter and reflected light meter; results were averaged. To test for oxidation buildup, testers placed a new cotton/polyester piece of cloth on a rotary disk and moved it slowly over each coating surface for 20 seconds, then noted any residue on the cloth.

To determine the hardness of each coating, testers used Gradcos pencil hardness test method: A roller device holding a pencil at a given angle was pushed across the surface of the coating; by using pencil leads of varying hardness, the coating was eventually scratched, and testers noted the hardness of lead required. We rated each performance on a 1-5 scale with 5 being the hardest. Tests were repeated five times.

To test for adhesion, testers used a scalpel to cut crosshatches through small sections of paint, then placed a piece of masking tape over the crosshatched surface, rubbed it and pulled it off. Paint pulling away from the surface detracted from the rating. All of the paints passed the adhesion test.

For the one-year report (PS, November 2009), testers evaluated abrasion resistance using a Scotchbrite scuff pad and 3 pounds of pressure; this test was conducted only on white paints. They used drops of dark tea (mimicking tannic acid, the culprit behind most waterline stains) to evaluate stain resistance.

Test Panel Findings

All of the topside paints that weve been monitoring fall into four categories: conventional enamel, modified enamels, two-part coatings, and water-based paints for marine use. Our tests found that when it comes to ease of application, the one-part products stole the show. But the highest marks for gloss, hardness, and durability went to the two-part polyurethane coatings.

Our intentional use of the term coating stems from the way these long-chain, polymer-linking paints behave. In essence, they are more of a catalyzed resin than conventional enamel. The latter loses solvent through evaporation during its curing process, while the former goes through a molecular crosslinking process that leads to both extra hardness and a wet-looking, high gloss. One thing we did notice in this field of super performers was that they come with some tradeoffs.

For example, industry leader Awlgrip (an Azko Nobel company) is the manufacturer of coating systems marketed for professional use only. Because their two lines of paints are available to the general public at West Marine and other retail chandleries, we included them in the test. These are not DIY coatings for the inexperienced, but the skilled and practiced DIYer-those already familiar with fiberglass repairs, applying epoxy primers, and fairing a surface, and who know what sanding to perfection really means-may be ready to handle professional-grade products like Awlgrip.

The top-rated Awlgrip behaves much like the other two-part products in our paint reviews, and it delivers the very best results. The companys top-coat bifurcation gives users two different products and approaches to two-part painting, and its worth a closer look. The makers traditional two-part, high-solids, polyester-based linear polyurethane (LPU) coating is named Awlgrip and its acrylic, modified two-part polyurethane topcoat is Awlcraft. The latter is easier to handle and allows a user to fix flaws in the finish or spot repair damage that occurs at a later date. Sags, hangs, or a fly doing the backstroke just after the final coat is applied don’t result in as critical a failure as they do with Awlgrip. With Awlcraft, wet-sanding and touching up is not as much of a Michelangelo-level skill as it is with Awlgrip because Awlcraft is a bit softer and can be rubbed out and polished back to maximum gloss in the same manner automotive paints are handled. However, as with all softer acrylic-based LPUs, theres a drop in abrasion resistance when compared with polyester-based LPU paints like Awlgrip.

Between top-rated, top-priced Awlgrip and much softer, brush-friendly one-part enamels resides an interesting array of chemical innovation. Traditional enamels like those made by Z-Spar, Kirbys, and Sherwin-Williams delivered good initial gloss but most deteriorated over the three-year test run. The good news is that none suffered adhesion loss or excessive oxidation, and an open can of alkyd enamel doesn’t have the harsh chemical odor that two-parts have.

Interlux and Epifanes urethane modified enamels outpaced old-style paints and nudged ahead of Pettits EasyPoxy. West Marines Sea Gloss Pro also delivered great results. CrystaLacs Crabcoat was the only water-based product in our test, and from the start, gloss was not its strong suit. But Crabcoat does offer good adhesion, durability, and an attractive semi-gloss, and for those working inside or in tight confines, theres the bonus of a low VOC level. However, when it comes to comparing one- and two-part paints, its important to note that theres a significant performance gap between them.

After three years of testing, its become clear that two-part paints are in a league all their own. All two-part coatings we evaluated had more shine and better adhesion at the three-year point than any of the single-can options. That said, there was a grouping of top single-part urethane modified enamels that surprised us with their durability and, to a lesser extent, their shine.

Interluxs Brightside and Epifanes Mono-urethane are case in point, and in our third-year panel evaluation, they earned high marks as all-around paints when it came to ease of application and durability. Perhaps the best test of their tenacity was how well they held up on the cockpit sole of Technical Editor Ralph Naranjos Ericson 41. (See Field Test Results on right) These paints have endured 3 years of sailing travails plus the onslaught of icy winters and boiling hot summers. The gloss has diminished some, but their adhesive quality as nonskid paints and waterway topcoats has been impressive.

Conclusion

When all was said and done, theres no question that the professional approach to a two-part paint makeover yields the best-looking results. However, there are a few shortcuts that do work and a few that should be avoided. One-part urethane modified enamels like Brightside, Epifanes Mono-urethane, and Pettits Easypoxy deliver handling convenience and a surprisingly long-lasting finish. Boat owners who have mastered the handling challenges of a two-part LPU sprayed finish can get close to the like new look of a professional paint job. But keep in mind that these coatings contain aggressive solvents and other unfriendly chemicals. Covering up and wearing an appropriate respirator and eye protection are part of the process.

We were glad to see that results from our three-year panel testing showed a strong correlation to our field test findings. The winners in both test groups paralleled paints highlighted in previous years. One of the biggest surprises, however, was that traditional enamels held their own, retaining good adhesion, despite losses in gloss retention. On the panels, all of the paint products remained well adhered, but a few failures in the field could be linked to shortcuts in preparation. We demonstrated that those looking to lessen the chances of ending up with flaking and peeling paint should consider using an epoxy primer and above all, follow manufacturer surface prep guidelines as closely as possible.

This weekend I saw my first example of a “vinyl wrap” as a topside application, on a 50’ Fontaine Pajot (sp?) catamaran. Almost overnight the boat Was transformed from an ordinary, dated, white hulled cat, to a like-new boat in a striking gray finish. How does this system compare to other topside finishes like traditional gel coat and two part finishes?

Hello D.N.;

thanks for the update on the topside paints but one question. I used EZpoxy polyurethane on my 1967 Morgan 24 this year and noted they offer the Performance Enhancer to increase hardness and durability. I used it as they advised and am happy with it thus far. The results are noticeably harder and cure faster and (for those who desire it) there is a higher gloss… Why have i heard nothing about the combination in various reviews including yours? It is an easy to work and forgiving topcoat…why no notice?

i am wondering about using an oil based exterior finish that is NOT a marine product… obviously these are much cheaper… any testing on this?

I have restored, modified, and repainted a few boats in my amature days. Full disclosure I am a former marine mechanic and have taught technologies for 20 years.

Brightsides has been an overall disappointment to me. In 4 attempts at repainting my Bluenose 24, (my brother in law is a rough landing skipper) I only had the gloss come up once. The other three times the paint kicked too early or just cured dull.

In putting an epoxy bottom coat on my Shark 24, with Pettit epoxy, that claims to cure even down to 5 celsius, the paint started kicking on the roller leaving a bumpy mess like a teen’s complexion. Pettit replaced the product and after exhaustive grinding off the previous mess, it happened again. Pettit is off my list forever.

Epifanes has been my go to choice for my trawler yacht, a Mainship Mk1. It has been the best experience of them all. Using a roll and tip method, the brush strokes did not level out leaving noticeable lines up close. I contacted Epifanes Canada and they now recommend just rolling, and they are right. Just roll it on and it’s great. Yes the mono urethanes are softer, but they are so much more user friendly when rolling on. A factor when some drydock locations would not allow spraying without building a full enclosure.

After my first season, a green dockhand caused a minor scratch with improper line handling. I called Epifanes and they advised just tape of a trapezoid shape around the scratch and repaint it. You will have to get real close to see the tape line. BAM! it worked just like they said. I now do not fear docking scratches as I know I can successfully with little fuss repair them during drydock times, or even afloat if need be.

I have no investment in any of these products. I am Epifanes sold. Awlgrip is too fussy for a DIY boatyard job. Unless you want to fork out big bucks, accept the 4 foot test. If it looks great 4 feet away, be happy.

Total Boat on deck. A forty years old non skid started to erode. Sanding was almost impossible: it grinned all sand paper and the majority of wheels. I decided to deal extensively and degrease. And coat of Total primer ( same color as the original ) was applied. A second coat after two days did not offer nay adhesion advantage, using the metal comb scratch and peel testing method. It was followed by one coat of Total Boat Wet Edge (white) mixed with 33% Total Boat Non Skid ( Light grey to match the primer ). I added 50% of Interlux flattening agent. The result is very satisfying. I liked the non-skid : its material does not settle as much as other manufacturers like Petit.

This system will be easy to maintain if necessary. It took 5 hours per coat on a 36ft deck, trapping included.

The temperature was above 65F. and the humidity was low. There was high wind that accelerated the drying process.

I’d be interested to read Practical Sailor writing on Total Boat products. This system was tested against test panels of Petit and Interlux. I did not see any major difference in adhesion nor ease of application.

Before tackling ANY large painting project, paint a few 1-to 2-foot panels, playing with rolling, tipping, and specifically, the working temperature and amount of thinner.

Never push the low temperatures or high humidity. Follow the instructions or the odds will incline against you. I avoid paint projects both spring and fall in cold climates–the weather is just not dependable enough. Instead, I target that part of the summer when the wind stinks anyway and sail in the off-season.

I’ve always been able to get the finish I wanted. I pick the weather, dial in the thinner, buy the best rollers and brushes, and prep ahead of time so that I can easily finish in one push.

As for non-marine finishes, Rustoleum Gloss Protective Enamel is dependable for little projects like brackets and backing plates. I always keep a can of white handy–exact color matching is not vital on small things. It takes fewer coats than yacht finishes and seem to hold up about as well. Every hardware store has it.