The following is an updated advisory regarding the care and use of personal flotation devices. It’s a relatively long post, but if you depend on an inflatable PFD, the text and accompanying links are worth reviewing. If you have some helpful links to add, please don’t hesitate to include them in your comments.

We don’t have to look far to recognize the importance of an auto-inflate PFD working as designed. The failure to inflate clearly appears to be a contributing factor in the tragic death of 52-year-old sailor Jon Santerelli at the start of the 2018 Chicago-Mackinaw Race. This following statement, issued shortly after the accident by Nick Berberian, Rear Commodore at the Chicago Yacht Club, describes what happened:

“At approximately 2:45 p.m. on Saturday Jon [Santarelli, age 52, aboard the TP52 ‘Imedi’] was moving toward the stern of the boat to make a routine sail adjustment. Unfortunately, at that precise time, a large wave hit the boat, causing him to slip into the water . . . Jon was wearing a personal flotation device that is designed to automatically inflate when it comes into contact with the water. The crew members have reported that the device did not inflate. . . .”

The accident is particularly disturbing because Santarelli was an extremely experienced sailor, he was sailing with a very experienced and well-trained crew, a boat that presumably should be equipped with first-rate safety gear. Since the PFD itself was cremated along with Jon’s body (found a week after the drowning), the reasons why the PFD did not inflate are unknown. The Coast Guard did examine the CO2 cartridge and concluded that it had not been activated. The Chicago Yacht Club’s investigation into the accident covers the event in great detail, and Appendix E, in particular, provides one of the most thorough discussions of PFD use and care that we’ve seen anywhere. If you are going to visit any of the links provided in this blog—go to that one.

We want to make clear that despite the shortcomings of current PFD designs, they remain an essential tool for survival at sea. Without reservation, PS encourages boaters to wear the appropriate type PFD while sailing, in any boat and any water. At present, a properly maintained auto-inflating PFD has proven itself to be a versatile and effective device for everyday use when offshore sailing, where great mobility and an abundance of flotation is required. However, it is important to recognize that auto-inflate vests are not our only option. Small boat and inshore sailors are often better served by a conventional inherently buoyant life jacket. It is important to weigh the pros and cons of each device when choosing the right one for a particular activity.

Finally, if you are new to offshore sailing and are dreaming about going cruising, the perceived risk of going overboard should not deter you. The rare events get wide attention in the media, and the “lost at sea” trope looms large in the public imagination. Practical Sailor along with most boating magazines are drawn to the topic of safety at sea because the stakes are high, but we also have a responsibility not to over-hype the risks, or inject anxiety where it serves no practical purpose. It is important to inform yourself on the topic, but with practice and common-sense precautions, you will never come close to losing someone overboard. But if you are among the very few unlucky individuals, abiding by the findings in this post will increase the chance of survival.

RANDOM TESTING

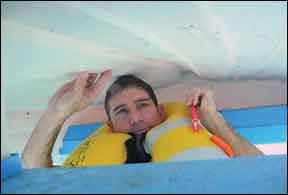

A few years ago, I had the opportunity to join Practical Sailor reader Joe Barnette and his friend and longtime crew member Demetri Lignos as they tested the inflatable lifejackets that Joe keeps aboard his Island Packet 465. Both Barnette and Lignos are members of the local U.S. Coast Guard Auxilliary in Sarasota, and Barnette has three trans-Atlantic crossings to his credit. Barnette is planning another ambitious voyage in the spring and he figured it was a good time to take a close look at his safety equipment.

All of the inflatable lifejackets were combination harness/vests designed to auto-inflate upon immersion. One was the Mustang 3184, our top-rated jacket from previous test. The others were Sospenders made by Stearns. The ages of the vests ranged from three to six years. Although they had been inspected regularly, none had been serviced. The presumption was that at least one of these jackets would fail to inflate, or would lose most of its air in 16 hours or less, the minimum time period recommended by any manufacturer.

The test took place in the pool at the Bird Key Yacht Club, overlooking Sarasota Bay in Sarasota, Florida, a few miles from our home office. Temperatures were in the 90s. While Barnette and I sweated it out poolside, Lignos was happy to play the part of guinea pig. He gamely plunged into the pool again and again, trusting his fate to the aging inflatable lifejackets. Our safe, nearly idyllic environment provided little insight into survival at sea, but in the same way that even an ideal first date can expose snags in a relationship, a quiet-water trial can offer ample clues of impending equipment failures; more importantly, there is little risk of drowning-unless, of course, things go terribly wrong.

The good news is that every one of the auto-inflating lifejackets that we tested inflated as designed. Within a few seconds of immersion, Lignos buoyantly bobbed back to the surface. The bad news was that the experiment, even in such tame conditions, pointed out many of the flaws with inflatable life jackets.

I’ve discussed the pros and cons of inflatable personal flotation devices (PFDs) in several blog posts and editorials in the past. And they are again addressed each time we test PFDs. Rather than rehash these issues here, I’m providing links below to some of the more relevant articles and tests. Even if you think you are intimately familiar with your inflatable PFD, I encourage you to review these links. And there is also our ebook on Man Overboard Prevention and Recovery, which covers this topic in depth.

COMMON MISTAKES, PRODUCT RECALLS

One mistake that sailors make with their inflatable lifejackets is that they fail to recognize that these devices require regular inspection, not just monthly or annually, but each time before setting out in your boat. In addition to pre-departure checks, there are seasonal and annual maintenance checks. If you haven’t reviewed the recommendations for your manufacturer, you should. I have provided links to the maintenance advice for two of the manufacturers below.

A second error is a failure to repack correctly. Some systems, especially the hydro-static devices that are triggered by hydrostatic pressure (rather than simple immersion), an incorrect packing can delay or prevent full inflation. Spinlock (equipped with Pro Sensor auto-inflator), Mustang (Hammar auto-inflator), and other manufacturers use these inflation systems, which are particularly popular among racers because they are less likely to accidentally inflate when the boat takes a bow wave and the wearer is doused in water.

In recent years, I’ve heard about device failures from safety experts who lead PFD demonstrations around the country. Sometimes the PFDs only partially inflate, sometimes they don’t inflate at all. Currently, there is no hard statistics on the number of such failures, nor have the precise causes in each case been thoroughly documented, but we have begun working with instructors to begin collecting this data. During these demonstrations, the participants inspect and re-arm the inflation system, re-pack, and don their own PFD (or one provided by the event sponsor), and jump into a pool. The purpose of the demonstration is to familiarize sailors with the gear, both on land and in the water.

According to those I’ve spoken with, one possible problem with the hydrostatic devices: if the water pressure sensor in the auto-inflator is blocked by the bladder or cover material during repacking, it might not trigger inflation, or auto-inflation could be delayed. Some testers have reportedly been able to duplicate this failure mode, and we are currently investigating this. It is clear that these devices are not immune to design problems. Over the years, several prominent makers including Crewfit, MustangSurvival, and Spinlock have all issued voluntary recalls over the past several years. Suffice to say that if you haven’t registered your product with the manufacturer and checked for any recalls, you should do this immediately. And if you are unfamiliar or have questions regarding the proper re-packing or re-arming of your vest (see links below), contact the maker.

PFD ADVICE

The Chicago incident isn’t the first time that an offshore racing event has prompted a discussion of inflatable PFDs.

Ron Trossbach, head of the US Sailing investigation into the Rambler 100 accident, offered several key findings regarding inflatable life jackets as a result of the Rambler 100 accident.

- Always wear your own life jacket, properly fitted and secured. A life jacket isn’t on until it’s complete with fitting/adjustment, crotch straps attached, and PLB and bright strobe on your person. The tether/harness must be attached (but not necessarily hooked on).

- Life jackets should be either on a person, hooked to their bunk, or otherwise immediately available.

- Inspect your life jacket every time you put it on and conduct an air test of your inflatable annually.

- Revisit the decision whether you want to wear an automatic or manual inflating life jacket. Familiarity with using the dump valve on your PFD was emphasized in our preliminary study of what can happen in a capsize.

- Know how to manually inflate your inflatable life jacket. Finding the pull cord is not always easy.

- Wear crotch/thigh straps (required by ISAF OSR 5.02.5 b on all harnesses since 2011). Know how to deploy and use your spray hood. (Splash guard/spray hoods are already strongly recommended by ISAF OSR 5.01 j.)

- Upgrade your whistle. The Fox whistle did best in our emergency whistle test. (Installed PFD whistles were considered useless.)

- Many PFD strobe light sensors must be in water to work, and they are not very bright.

- We offered our own recommendations in regarding both PFDs and harnesses in our analysis of the report on the fatal capsize of the racing sloop Wingnuts in 2011.

- Tether quick-release snap-shackles do not consistently release when the tether is under loads of greater than about 150 pounds. So if you are being dragged behind your boat, you will likely have to cut yourself free, or relieve the strain on the tether with a great deal of arm strength before you can trigger the quick release.

- Accessing the tethers quick-release mechanism when hooked into inflated harness/PFDs can be extremely difficult.

- When not in use, boat-end tether clips or clips on two-leg tethers should never be attached to the harness. Only a single quick-release snap-shackle or similar device should be connected to the harness.

- Auto-inflating harnesses can prevent deaths due to the gasp reflex, in which a drowning victim (typically in cold water) reflexively ingests water, but they have shortcomings, one of which is prevent escape from an overturned vessel or flooded cabin.

- Know how to deflate your inflatable PFDs. Trying to escape from a sinking or capsized boat, reboarding a boat, or boarding a life raft in an inflated PFD can be extremely difficult.

- A sharp knife should be kept handy at all times while underway. We’ve tested several knives over the years, some of our favorites are featured in this Practical Sailor sailing knife test.

- Personal locator beacons (PLBs), whistles, and lights that are worn at all times can be valuable lifesavers.

Past PS Tests and Maker Links

We’ve carried two major tests of inflatable PFD/harnesses in recent years, with several smaller follow-ups.

Safety expert Ralph Naranjo looked into the auto-inflation trends in contemporary PFDs for Practical Sailor and how this might prompt us to revise our protocol for going overboard. Among the many useful conclusions of the study, he advised sailors to reach for the manual inflation pull-cord as soon as going overboard becomes imminent, rather than wait for the auto-inflation to activate.

In “Rethinking the Use of Inflatable PFDs,” Naranjo examined the utility of inherently buoyant PFDs and the role they play in personal safety for all sailors—from offshore cruisers to near-shore dinghy sailors. Although inflatable harness-PFDs are more likely to be worn at all times, recent accidents have highlighted their shortcomings. As Naranjo points out, many professional marine pilots who are involved in risky boat-to-boat transfers in all kinds of weather trust their lives to inherently buoyant PFDs for a reason.

In 2006, noted offshore sailor Skip Allen tested several models in the cold waters of California. And in a followup life-jacket harness test in June 2008 we tested at three fairly new entries to the field, representative of a trend toward light-weight models. Although both of these tests appear fairly old, safety design tends to evolve quite slowly. Most of these products, or near copies are still on the market today.

Maintenance guidelines vary slightly by manufacturer, but the guidelines offered by West Marine in their do-it-yourself checklist for inflatable PFD maintenance will generally apply to other brands.

Mustang, maker of one of our top-rated inflatable PFD harnesses, the 3184, offers its own series of Mustang Survival YouTube videos demonstrating re-arming. It is important to note that two versions of Mustang PFDs have been subject to recall, including the later version of the 3184.

For those looking for instructions on re-arming their PFD my editorial on the elusive perfect fit featured the following links.

Mustang Automatic MD3053, MD3054, MD3083, 3084

Deckvest Hammar 170N

Deckvest VITO

Landfall Navigation, one of the leading providers of safety equipment, also offers a number of useful videos and links to manuals.

We reported on concerns raised about the Spinlocks popular (and expensive) low-profile lifejackets in the aftermath of an accident in 2012.

We looked at the Spinlock along with some more conventional inherently buoyant PFDs in 2013.

This leads me back to Michael Garman, the winner of the BoatUS 2015 Innovation in Lifejacket Design Competition. I was pleased to see that he did not fuss around with inflators and instead focused on proper fit. If there is one thing that Barnette, Lignos and I agreed on, any PFD/safety harness, whichever the brand, must fit snugly to perform properly. In some designs, in order to prevent the PFD from riding up under the arms of the wearer when he’s in the water, the straps must be so snug as to almost be uncomfortable. For a couple of the test inflations we intentionally loosened the straps on Lignos’s vest. When he bobbed to the surface he was dangling precariously from two buoyant bubbles, struggling to stay afloat. It was comforting to see that each of the vests inflated as designed, despite having had little maintenance or attention over the years, but after all the testing was complete I couldn’t escape the conclusion that inflatable PFDs have many inherent weaknesses-and that it was a good thing we weren’t at sea.

[/su_box]

Inspecting your PFD requires more than a cursory look a the exterior. The PFD should be inflated and left overnight. If there is any noticeable sign of air loss, inflate the PFD again and immerse it in a bath with soapy water and look for any bubbles indicating a leak. Except for tiny bladder leaks (not at seams) when there is no other repair option, dont try to repair your own PFD.

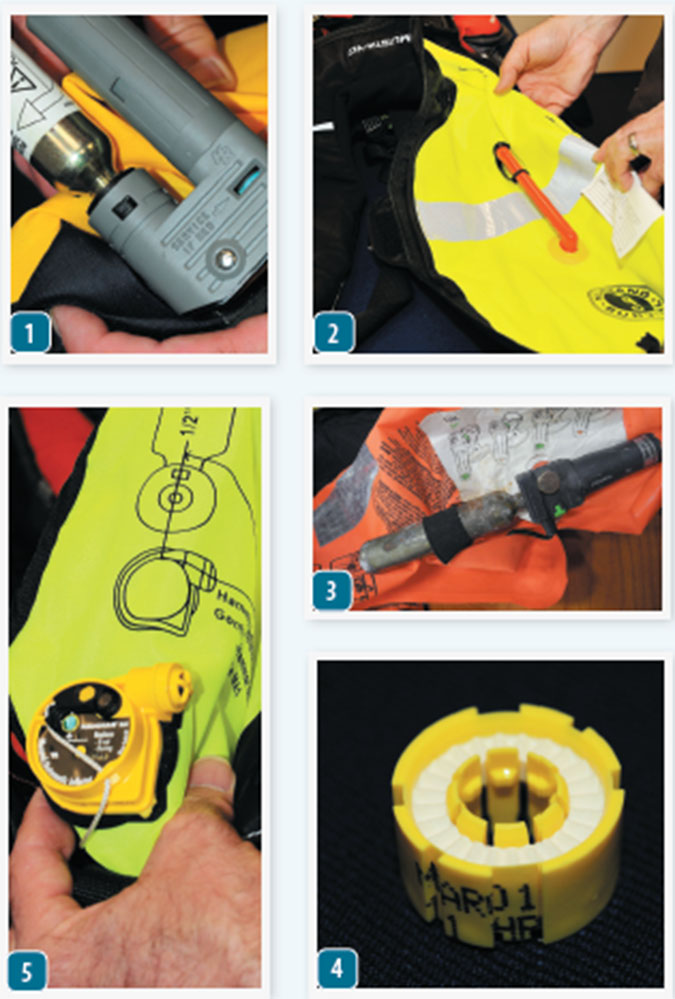

- Halkey Roberts inflators have a green indictor illustrating that the cannister has made a positive connections.

- Every owner should know how to quickly access the manual inflator. Sometimes this inflator is not exposed unless you manually unzip or open the PFD.

- Any older inflatable PFD that shows deterioration should be replaced or sent back to the manufacturer for evaluation.

- Each bobbin is dated used for calculating shelf-life. Check your manual for service life, which varies by model and type of use.

- This Hammar inflator activates on pressure. Newer models of the Spinlock jackets have vent holes in the material to expedite inflation.