Darrell Nicholson

Reader David Brezina, who sails a Tartan Ten out of Montrose Harbor, Chicago recently had a question for Practical Sailor regarding drinking water. Like many Great Lake sailors who race seriously, or who own boats that were once raced, his boat has had its permanent water tank removed. After all, when you sail on a virtually limitless supply of drinking water why bother with a water tank?

Brezina wondered if the General Ecology QC2 filter we reviewed in August (see Effective, Affordable Water Filters, PS October 2013) would be enough to make the lake water safe for drinking.

The short answer is probably, but to be safe wed take a couple extra steps. Theoretically, a filter that meets the National Sanitation Foundation (NSF) P231 standards will be sufficient to make Lake Michigan drinkable (see Making Sense of Water Filter Certification, PS August 2016). A more effective (but more expensive) choice would be to use a filter that meets the more stringent NSF 53 standard. Although the General Ecology filter that you are referring to is not certified to either standard, the maker has had it independently tested “over the years” to ensure it meets or exceeds NSF 53. Many Great Lake sailors use manual or battery-operated water purifiers that campers and hikers use in the backcountry. These products, typically certified to P231, are usually low-volume systems. We’ve reviewed several (see the Grayl system in “Stocking Stuffers for Sailors,” December 2012, the Camelbak All Clear, “Summer Sailing Gear,” June 2013, and the SteriPEN Portable UV Water Purifier, September 2008). There are higher-volume systems billed for use in third world expeditions, but these can cost as much as a watermaker.

Although these portable systems have proven effective in making lake and river water safe for drinking, a cost-effective way to be even more certain that your drinking water meets safe drinking water standards is to follow the three-step process that we outlined in our series on treating onboard drinking water. Designed for treating larger volumes of water, the process would be easier to carry out if you had a portable tank (look for FDA-approved food grade materials). If you do not want to find a permanent space for an FDA-approved food grade rigid tank similar to the holding tanks that we tested in 2012 (See Marine Holding Tanks go Head-to-head, PS February 2012), a bladder tank is another option. We have tested several flexible potable-water tanks that would serve well (see Practical Sailor Drags, Drops, and Dissects Three Flexible Potable-Water Tanks, PS October 2002). You could also use jerry jugs or similar container used by car-campers.

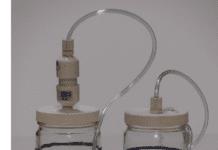

First, you need to prefilter the water to remove dirt before it goes into the tank. The 1-micron Baja Filter that we wrote about in 2015 is a favorite tool for this, but we looked at various other filters that will prevent solids from getting into the tank (see Water Tank Filters, PS June 2015). Clean water is required for the next essential step, chlorine treatment.

Chlorine treatment will kill viruses and bacteria. Although regular liquid chlorine will work, it isn’t ideal for storing aboard. We found pool and spa chlorination tabs to be a convenient alternative for chlorinating tank waters (see Keeping Water Clean and Fresh, PS July 2015). The key to any chlorination regimen is using the right amount of active ingredient (described in detail in the above linked article). You should use only enough chlorine to leave a one part per million (PPM) residual chlorine after one hour. You can use a pool test kit, or aquarium test tape strips to check residual chlorine.

Finally, you need to filter before the tap with a filter element that is rated to remove cysts such as giardia and cryptosporidium. Weve tested several filters that are rated as microbial purifiers, meeting the P231 standard (see “Tap Water That’s Better Than Bottled,” PS August 2015). These filters are capable of removing all viruses and bacteria. Last but not least, if you have a permanently installed tank, don’t forget to secure the vent. The freshwater tank should have a #20 mesh screen to keep bugs out.

Although this multistep step process might seem like overkill, it is very similar to that used by municipalities that draw their water from the Great Lakes. It is still possible that naturally occurring algae blooms can introduce toxins that these steps wont catch, but this is very unlikely. Because these toxins pose a threat to drinking water supplies, their occurrence is usually monitored by local municipalities and reported in the local media. Another very unlikely problem would be drawing from areas contaminated with industrial pollutants or harmful chemicals that might foil this treatment process-again, one would hope the presence of these contaminants would be made public information in a timely fashion.

Fortunately most areas of the Great Lakes remain relatively pristine and are a safe sources of drinking water that is easly treated on board a sailboat. If you have found an effective system for treating lake water-whether it’s a local lake or the Great Lakes-we’d like to hear about it. Include your tips in the comments section below or send them directly to the editor via email at [email protected].

[Editor’s note: Original has been corrected to correctly identify NSF as the National Sanitation Foundation.]