286

The ultimate in trivial significance is probably Richard III’s lament about losing a battle for lack of a nail. By contrast, use a nail in a fiberglass boat and it’s likely the boat will be lost. Nails as well as wood screws have little application on a modern boat. The reason is simple: almost any fastener will do a better job than either.

In this day and age the most practical fastener material is stainless steel. Stainless, as used in marine fastenings, is strong, corrosion resistant, and galvanically the most passive of fastener materials with the exception of bronze. Best of all, it is commonly available, even in areas where anchors are regarded as an odd example of freeform modern sculpture.

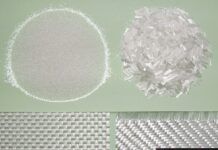

Let’s take a close look at the choice of fasteners available to the boatowner:

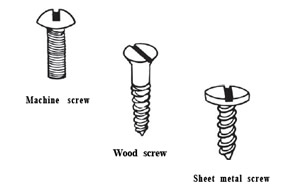

• Screws There is not much aboard a boat that the sheet metal (also called self-tapping) screw can’t fasten. Sheet metal screws are, of course, ideal for screwing into thin hard metals or even moderately thick (up to 1/4″) soft metal such as aluminum. All it takes is a drilled pilot hole of the optimum diameter.

The sheet metal screw works almost as well for most woods used aboard boats. It comes in a variety of head configurations in sizes up to #14 and in lengths from 1/4″ to 3″. It can be countersunk and bunged or left with the head flash.

Yet where sheet metal screws excel is in fastening into fiberglass laminates, whether cored or solid, to carry light loads. Where they are used wrongly is as a substitute for bolts for heavier loads. As with any screw the strength of the fastening itself is generally greater than its holding power; it will pull out before it will break off. As a rule of thumb the laminate into which the screw is driven should be at least equal in thickness to the diameter of the screw.

For all their virtue, sheet metal screws do have some notable limitations and drawbacks. The number of times they can be removed and redriven is finite — sooner or later they wear out the hole, diminishing their holding power. Holding power is similarly reduced if the pilot hole is oversized. They may be impossible to drive if the pilot hole is undersized. Remember too that the holding power of the screw is no greater than the strength of the material into which it is driven. Soft woods, thin laminates, and thin metal cannot carry much loading.

Conventional wood screws might serve to fasten wood joinerwork but should never be used to fasten into fiberglass laminates.

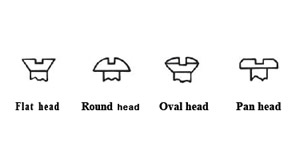

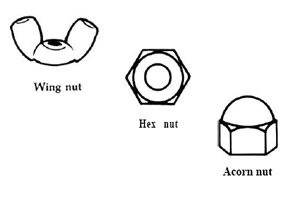

• Bolts For heavier loads, for pulling two surfaces together, and for fastenings that may be repetitively tightened and loosened, bolts are the answer. These func-tions are in direct contrast to those screws perform best. Bolts come with flat heads and round heads, both slotted; hexagonal and square heads for wrenching; recessed (socket) heads for Allen wrenches; and oval (carriage) heads. Their nuts are hexagonal, square, wing (for hand tightening), jam (self-“locking”), and cap (acorn), all capable of taking a variety of washers underneath. Bolts into heavier metal (equal in thickness to the diameter of the bolt) may also be used without a nut by drilling and tapping the hole.

300

Nuts are intended to be tightened against a washer that not only spreads the load on the underside surface of the material being bolted but prevents the nut from being turned into that surface. As many applications aboard a boat involve heavy localized loading, more loading than a mere washer can handle, bolts may need a hard backing block — aluminum or fiberglass — in addition to a washer, to better spread that load. Bolts should also be used in conjunction with a good sealant, as the hole through which they are set provides a passageway for water.

• Rivets Pop-Rivet is a brand name, but rightly or wrongly the term is becoming generic for the type of blind fastening that expands when the center pin (mandrel) is extracted and broken off. Such rivets are commonly used in applications that would call for a bolt but where location prevents turning on a nut (eg, in attaching mast fittings). Since rivets are also quicker to install, they are frequently used instead of bolts in production applications (eg, hull-to-deck joints on smaller and cheaper boats).

Pop-rivets are of two materials in combinations, aluminum and stainless steel, the steel for heavier loadings. The center pin is pulled, expanding the body of the rivet, until the pin breaks (“pops”). They may be set up with either a hand tool or a hydraulic tool. A word of warning: squeezing the hand tool is a macho exercise, dif-ficult for the aluminum rivets, herculean for the stainless steel.

Removing rivets entails drilling them out, a job that must be done carefully so as not to enlarge the hole through which a replacement must fit. In removing rivets, say, from a mast for painting, you may want from the outset to plan to use the next larger diameter to replace the fitting.

300

• A Word about Costs and Other Matters

Fastenings bought one by one or even a dozen at a time are outrageously priced. A 1″ #10 sheet metal screw runs 10c: or 12c: each. Bought by bulk, typically 50 or 100 to a box, they run closer to 44: apiece. At $4 a box, the same money that buys 100 buys three dozen. If the extra 60 are more than you want to pass on as part of your estate, sur-prise your fellow sailors by a gift handful.

Another point. A well found yacht does not need a nearly infinite variety of fastening diameters and lengths. We built a 34-footer with six basic fasteners: 1/4″ flat head machine screws in two lengths, a box or two of 3/16″ machine screws, #10 and #12 sheet metal screws in two lengths, and to save money a couple of sizes of plated wood screws for the joinerwork. Of course, for special jobs such as attaching the toerail we used a separate order of fastenings and because of the annoying lack of unifor-mity by fitting manufacturers, a number of odd sized fastenings for attaching fittings. (Why the hell do they drill their products so that a 1/4″ bolt is 1/64″ too large?).

Keep in mind that where the underside of bolts is hid-den the overlength of the bolt makes no difference except to the perfectionist or the hot racing type for whom any extra weight is a cause for fantods. At the same time, don’t leave the extra where it can crease the skull or snag a sail.

And one more point. Don’t be tempted to bed a fitting in an adhesive such as 3M 5200 or Sikaflex to add strength to the mechanical fastening. A properly fastened fitting will usually tear the structure away before the fastenings fail anyway, so the adhesive is redundant. At the same time, an adhesive should not be used to beef up inade-quate fastenings (ie, screws rather than bolts, or too small fasteners). The reason: it may be impossible to remove the fitting at some future date. There is a place for such adhesives but not as a substitute for conventional sealants.