When we downsized from a cruising cat to a sporty trimaran, we also downsized to an Origo stove. Familiar to many small-boat sailors, the simple stove has a reservoir that you fill with fuel. A wick draws fuel up from the reservoir to the chimney-shaped burner.

The first Origo stove I saw reminded me of a cross between the laboratory alcohol burners of my youth and a giant can of Sterno. Over the years of use, I learned firsthand about the problems people have with them, and just how simple the solutions are. There’s a lot of misinformation about alcohol stoves floating around.

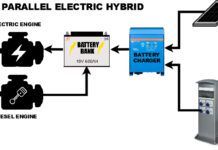

First, to clarify what we’re talking about. The Origo stove is unpressurized. A pressurized alcohol stove, by comparison, has a pump to pressurize the fuel and propel the liquid through tiny jets for burning. Older pressurized alcohol stoves had a bad reputation for flaring up and burning users, but many of those accidents could be attributed to user error—rather than fatal design flaws.

The biggest complaint with the Origo stove is the low heat output. When new, a wicking alcohol stove burns at about 4,500 BTU/hour when the reservoir is full of 50/50 ethanol/methanol denatured alcohol. The output tapers to about 4,000 BTU/hour as the reservoir empties over a 4 to 5-hour period. As the wicks age, peak heat output drops to below 4,000 BTU/hour and the burn time becomes proportionately longer.

You can compare the alcohol stove’s modest output to that of a small propane stove—6,000 and 8,500 BTU/hour. We recently tested our Origo stove side-by side with our home gas range. The Origo takes about 9 minutes to boil a liter of water, compared to about 7 minutes on the smaller gas burner and 51/2 on the larger burner.

VALUE GUIDE: RELATIVE FUEL COSTS

| FUEL | BTU/POUND | COST, $/GALLON | COST/1,000 BTU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | 11,500 | $18 | $24 |

| Butane | 19,000 | $36 | $40 |

| Propane | 21,000 | $3.65 | $4.25 |

| Diesel | 20,000 | $3.40 | $0.25 |

If you want to improve your alcohol stove’s performance, a pot skirt can improve efficiency. A strip of flashing or other thin metal fitted about ¾-inch from the pot creates a chimney that holds the hot exhaust against the pot. This improves heat transfer and reduces boiling times by 15–25 percent (see “Pot Skirt: DIY Cooking in the Wind,” PS, August 2016).

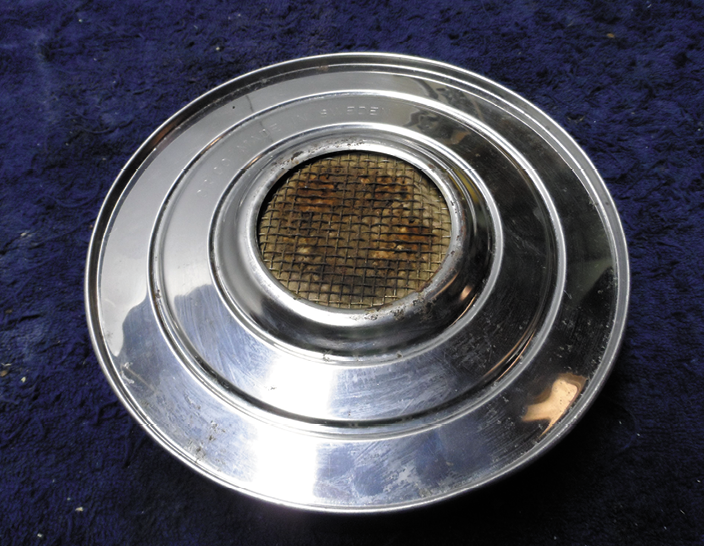

FUEL RESERVOIR CARE

Contaminated fuel reservoirs reduce heat output. The canister is built using a donut-shaped ring of densely packed mineral wool around the outside, with a glass fiber core up the middle and a sheet of glass fiber on top, just under the wire mesh. Contaminants in the fuel, primarily high-boiling denaturants and fusel oils, migrate upwards with the fuel to the glass mat, where they concentrate and dry into a gunky black residue. Food spills also reduce output.

Another problem is water. If the alcohol contains more than 5 percent water, the excess remains in the canister. Heat output drops until the mixture is around 25 percent water. Leaving this water in the reservoir can lead to corrosion from the inside that creates pinholes.

The cure? Let the canister run empty and then let it dry for a day. Burn any organic residue under the screen to ash with a propane torch, loosen it with an old toothbrush, and blow it off. If water has accumulated from burning wet alcohol, allow the alcohol to evaporate from the reservoir for several days, and then dry completely in an oven (low heat) for a day. The heat will not damage the fill.

Corrosion is a problem. The reservoir, including the flame screen, is made of stainless steel, and the Achilles heel of stainless is chloride. Raise the temperature and corrosion is worse. Some chloride comes from the salt air, but food spills are the greater culprit.

Ethanol will never be the cheapest fuel. For the weekender, a gallon will last all summer and cost hardly matters. It will be cheaper than butane or propane cartridges. For the active cruiser or live aboard, based on both cost and our experience with a variety of stoves, propane seems like the obvious choice, so long as you are committed to installing it according to code and keeping up with the maintenance.

Many users pour only as much fuel in the reservoir as they will use for a meal, fearing the remaining fuel will evaporate. This reduces heat output. In fact, your stove originally came with a rubber gasket to seal the reservoir between uses, but most of these were lost by the original owner and subsequent owners never realized they needed one.

Origo gaskets (original and knock-off) can be found on-line for about $6, but you can make your own by simply cutting a 41/2-inch circle from 1/8-inch neoprene, nitrile, or even butyl truck tire innertube (but not polyurethane). The original design was cup-shaped, to match the shape of the reservoir, but a flat gasket works just as well. The gasket also eliminates cabin odors and reduces evaporation to a small fraction of an ounce per month.

After use, allow the stove to cool for just a few minutes, lift the top, place the gasket on the reservoir, and close the lid. The closed flame regulator plate provides sealing pressure.

FUEL STORAGE

Pouring fuel from a steel hardware store can is awkward and spills are common. Instead, transfer the fuel to a container that pours well. We’ve found several good options for storing and pouring alcohol fuel.

MSR Bottles. Backpackers use aluminum fuel bottles from Sigg (discontinued) or MSR. Although MSR has stopped making bottles with a pour spout, the Trangia spout is available separately for $10 and fits Sigg and MSR fuel bottles. Price is about $20 for a 16-ounce bottle.

Trangia. Made in Sweden, these polyethylene fuel bottles are suitable for alcohol, gas, diesel. Unscrew the lock, push a button, and the fuel comes out in a neat, regulated stream, perfect for topping off the reservoir. The cap vent mechanism extends into the bottle a short distance, so don’t fill above the fill line. Cost is about $19 for 1 liter.

Scepter Smart Control Fuel Can. Planning a longer cruise? Featuring a flame mitigation device and a simple way to control pouring, the 1-gallon Scepter tank makes for an exceptionally safe choice. Since it is primarily used for gasoline and looks like a gas tank, be sure to label it for alcohol-only. Price is about $15 for a 1-gallon can.

FILLING THE RESERVOIR

Never fill a hot stove. Because the flame is nearly invisible, it may still be lit, and that flame can flash back into the bottle. This will cause over pressure in the bottle and force a spray of flaming alcohol out of the bottle, burning anyone around it. Also, don’t fill the canister while it is in the stove. It is smarter and safer to fill the stove according to the instructions.

Remove the canister from the stove, place it in a safe location (cockpit or sink), tip it to a 45-degree angle (to help saturate the wick), and stop before it overflows. Clean up all spills; it looks like water, but it is flammable. If possible, fill the canister before meal preparation, avoiding the temptation to refill when hot. If it is hot, quench the top of the canister with a moist washcloth and wait until all surfaces are cool enough to hold. As an additional safety precaution, consider fuel in bottles with flame mitigation devices (Smart fuel) or use a gas can with a flame mitigation device.

A large soup can, cut down and with ¼-inch hole punched in the center, is sometimes suggested as a funnel. The hole slows the flow enough so that the fuel can soak in, and punching the hole, rather than drilling, keeps the stream centered. The downside is that you can’t see if you overestimated how much fuel would fit, resulting in overfilling.

Fires related to spills are completely avoidable. Properly filled, the reservoirs leak very little fuel even inverted. If you do start a fire, extinguishing should be relatively easy. For a larger fire, due to the very unlikely failure of the cartridge, cover the flames with a fire blanket and douse with a lot of water. Dump a whole bucket on the fire blanket if you have to.

CONCLUSIONS

If you have an Origo stove, treat it gently and burn a recommended fuel alcohol (see adjacent story). We liked the more luminous flame and lower odor of ethanol fireplace fuels, but these fuels seem a little expensive and we didn’t like soot on the pots. The choice between ethanol and 50/50 ethanol/methanol fuels comes down to personal preference.

Clean the reservoir to maintain peak efficiency, and when you eventually need a replacement reservoir, you should be able to find a good one on the used market, and with some newer stoves emerging the reservoirs should be available in the foreseeable future. Store your fuel in smaller containers to reduce spills and follow safe fueling practices to avoid flame jetting and other fire hazards.

CONTACTS

MSR, msrgear.com

SCEPTRE, sceptre.com

TRANGIA, trangia.se