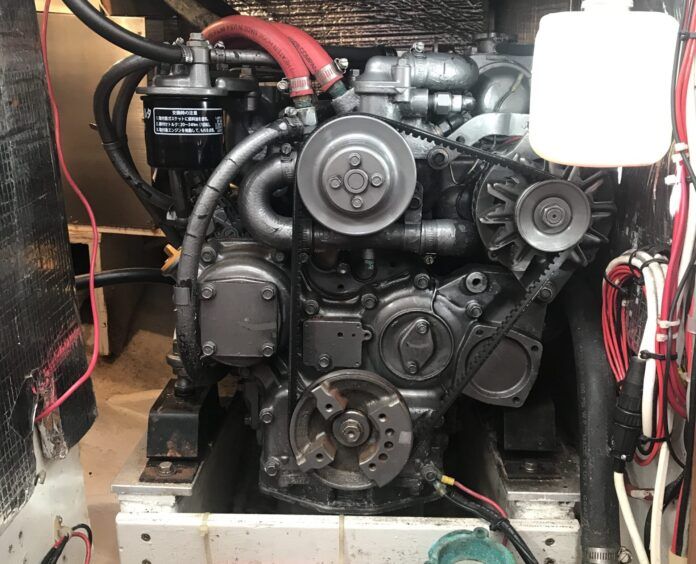

If you want to know more about the little Yanmar chugging away in your sailboat, it helps to learn about this iconic engine maker’s lowly but ubiquitous GM series. This noisy, cantankerous, yet well-regarded machine will nonetheless take you anywhere you want to go. You just have to know how to treat it right—with respect, but a firm hand.

It is built to be simple, reliable and easy to repair, even in remote locations. Sailors who venture far from help and resources can literally rebuild this engine in the cockpit of their sailboat, as it doesn’t require any hard-to-access specialty tools, and is rather forgiving when it comes to assembly missteps or poor maintenance.

It is the “Toyota” of the industry, and it’s extremely tolerant of corrosive conditions, owner neglect, and poor operating practices.

As a marine mechanic, I have found that sailboat engines take some of the worst abuse an engine can withstand, from lack of maintenance, to simply not running the engine hard enough, which can wreak havoc on a small diesel. And yet, I have seen many Yanmar GM series engines still running with cracked pistons, saltwater in their cylinders, sludged oil in their passageways, and many other hideous conditions where any other engine would’ve failed. How is this possible? What is so special about Yanmar’s tough-as-nails, gnarly little GM?

SOME COMPANY BACKGROUND

Whether you are an experienced sailor, or you are getting ready to purchase your first sailboat, you are likely familiar with the Yanmar brand name. It should be familiar, as a Yanmar diesel engine is installed in approximately 50% or more of today’s recreational sailboats and powerboats. You can barely walk down the dock at a marina without passing one or more boats with a Yanmar engine installed. That said, why are they such a popular engine choice in the recreational boating world? Are they as reliable as everyone says they are? Are they always so on a “cool” day like everyone says? What’s their secret, and why is there such a following?

Yanmar has been in the business of building engines for more than a hundred years, and was the first engine manufacturer to successfully downsize a diesel engine in 1933 before entering the marine market in 1947. Not only do they build some of the world’s largest marine diesel engines, they also build the world’s smallest. The Yanmar GM is one of the United States’ most popular sailboat engines, and includes the 1GM10, 2GM20F, 3GM30F to name a few.

Like its earlier HM and YSM predecessors of the 60s and 70s, Yanmar’s GM series is a compression-dependent engine. Unlike equivalently sized engines from other makers that use glowplugs and intake grid heaters, however, the GM series engines have a much higher compression ratio. This means the engine can create its own heat within its cylinders in a significantly shorter time frame than, say, a Universal/Westerbeke, which has a significantly lower compression ratio, and thus requires glowplugs to get started. Without a lot of compression and heat inside the cylinder, diesel fuel doesn’t like to combust. A diesel engine needs fresh air, clean fuel, and good compression (creating lots of heat!) in order to start and run! This means a Yanmar can start in the coldest conditions without glowplugs, which eliminates a potential failure point. This also gives a Yanmar owner a unique perspective on the internal health of his or her engine. It will start relatively easily in the cold when new, but if you notice it getting harder and harder to start, even on warm days, that’s a sign compression may be dwindling. Thanks to the salty and damp environments these engines live in, I see many Yanmar compression-based engines struggle to start due to corroded valve seats. Why? While Yanmar succeeded in building a simple, reliable engine, they failed royally with their exhaust elbow design. Yanmar’s original equipment elbows, especially the mild steel L-style and cast iron U-bend style elbows, can fail in a variety of ways and is one of the reasons I sometimes wind up pulling off cylinder heads. Bad exhaust elbows means water intrusion and wet exhaust, weakened valve seats and finally, weak compression. As Yanmars age, weakening compression afflicts older Yanmars more than any other issue.

The faulty exhaust-elbow topic is likely a broken record for those of you who are aware of it. But take note of this problem if you own any Yanmar (including newer models) or are looking to buy a boat equipped with a Yanmar.

While we are on the subject of Yanmar exhaust elbow, let’s take the time to have a little introduction to corrosion and metallurgy. First, exhaust gases are extremely corrosive. Mix several hundred hot/cold heat cycles. Then, because of that bad exhaust elbow, add to the stew backed-up freshwater or even saltwater! If you think that mild steel or cast iron can withstand all that – think again. Yanmar’s OEM elbows tend to corrode terribly from the inside out, where you can’t see the damage until it’s too late. This is usually when the elbow finally breaks apart or water starts going backwards into the exhaust manifold. Eventually, raw water makes it into the cylinders. Remember what I mentioned about corroded valve seats leading to poor compression and starting issues? I have seen Yanmars running with water in their cylinders, the number one reason valves and piston/rings fail. The source? Water intrusion from a failed exhaust elbow. The U-shaped iron elbow is notorious for this, but it doesn’t stop there. The elbow is technically water jacketed, but the water jacket actually cuts the dry exhaust stream in half, reducing the engine’s ability to clear its own exhaust, and leading to power loss when the elbow becomes clogged with soot and carbon deposits. It will become clogged, that’s a guarantee. While Yanmar isn’t the only manufacturer with this issue, their factory-designed elbows are the worst.

WHAT CAN A YANMAR OWNER DO?

Luckily, there are some decent options to prevent catastrophic failure. If you are running an OEM mild-steel or iron elbow, every year or two it is critical to remove the elbow from the engine and inspect for signs of internal corrosion. This also gives you an opportunity to clear out any carbon buildup so the engine can breathe and not lose power. One solution is to replace a cast exhaust elbow with a stainless steel version. While Yanmar doesn’t offer stainless-steel elbows, a great resource for high-quality 316-grade cast stainless exhaust elbows (that actually cost a lot less and last significantly longer) is HDI Marine in Vancouver, WA. HDI Marine is a great resource for a variety of quality OEM-style elbows for Yanmar, Volvo, Detroit Diesel, and many more.

Another notable Yanmar quirk includes the air cleaner/silencer side of the engine. This is a common fault on many small marine diesels of the 70s-90s era, where many manufacturers never installed an actual air filter on their engines, thinking incorrectly the engine on a sailboat couldn’t possibly suck up any dirt or other crud during operation. Yanmar’s air cleaners consist of a mild steel screen with a foam “filter” installed underneath a steel housing. This filter is not resistant to oil or fuel. Yanmar and other diesel manufacturers route their crankcase vent hoses into the air cleaner. Routing the vent hose this way prevents an oily mess from oil vapor condensing and dripping down the side of the engine—just like they did in the ‘olden days’. But what happens when the foam filter and engine oil mix? The foam disintegrates, breaks apart, then gets sucked into the engine. I have found many engines with only the metal screen left, the foam long gone. Now if that isn’t a good way to encourage some premature wear and tear on the engine, I don’t know what is! If you’re checking out a Yanmar onboard a potential boat to buy – pop open the air cleaner and check. If the filter is gone, you’ll get a good idea as to the maintenance habits of the previous owner! If you are currently an owner of one of these Yanmars, get in the habit of checking/replacing it every 100 hours or every oil change to keep it in tip-top condition. This will keep it out of your engine’s piston rings!

Finally, two things I commonly hear from owners: Complaints about Yanmar’s notorious noise and vibration. Earlier Yanmars (HM, YSM, and GM Series) are particularly loud, as they have a notable “fuel knock” when running. When I first heard one of these engines, I honestly thought it was about to throw a connecting rod. Little did I know, the design of the pre-combustion chamber and the injector nozzle itself make for a very noisy injection event when fuel is squirted into the chamber and fires almost immediately. This is normal, and something many of us have gotten used to on our own boats. However, if you value hearing any conversation over this engine, consider a more modern (and quieter!) Yanmar YM series. Another gripe: Yanmar’s older-style motor mounts get regular complaints, but they’re not only found on older models. They are still used on brand-new engines of every model in the Yanmar line. The problem? Yanmar’s OEM motor mounts are particularly soft, allowing the engine lots of movement as a result, even if all other vibration sources have been tamed. These mounts are also notorious for delamination from their steel supports because the rubber can degrade when it makes contact with oil/diesel fuel. This causes vibration to get worse as time goes on. The original mount brackets are also built of mild steel, which will corrode over time. Aftermarket companies such as PYI Inc. and Oceanic Innovations sell higher-quality OEM mounts that perform better than the originals. Many clients who choose a stiffer engine mount have been pleased with the results.

Even though I have noted the GM series’ water-intrusion problems, I believe Yanmar does pay attention to corrosion resistance in most components. Yanmar has built their marine line of engines to withstand damp, wet and salty environments, and they have certainly demonstrated that ability with high-quality construction in engine blocks, engine paint, heat exchanger tube bundles, and other parts. Unlike some other small-engine manufacturers (apart from Volvo), Yanmar designs and builds its product line exclusively for the marine environment. Other manufacturers might marinize a tractor engine block for sale to boaters. Yanmar also built raw-water engines equivalent to their fresh-water (or coolant) cooled counterparts as a cheaper alternative to the cost of a new engine. While these engines were considered “disposable”, many of them have lasted 40+ years and some are still running to this day. Yanmar’s raw-water engines are quite unique in the fact that the water jackets inside the engine block are porcelain/ceramic coated to protect the iron block from excessive corrosion and damage, particularly in saltwater. While most everything will corrode over time, these blocks far exceed the longevity of a raw-water cooled Universal M15 engine block, for instance, which was initially designed for use in an excavator far removed from any salt water. Another notable fact: Yanmar took special care to design its heat exchanger cores and housing end caps to withstand years of corrosion without protection from a zinc anode. Unlike many of Yanmar’s competitors, who use copper and aluminum heat exchangers, Yanmar uses silicon bronze end caps and a cupronickel tube bundle that is nearly perfectly resistant to corrosion over long periods of time. These tube bundles can last 20+ years as opposed to 5 or so years with a cheaper heat exchanger, which often results in raw-water coolant contamination.

A common question I get as a diesel mechanic working with a lot of different engines is whether or not I would recommend a Yanmar and why. Short answer: I absolutely would. While many manufacturers on the recreational engine front build reliable engines, Yanmar’s attention to detail and continued support is what keeps me onboard as a mechanic, but also as a customer. While all engines have their quirks, as we’ve discussed here, Yanmars enjoy good construction, good design, and a well-supported network that keeps parts available. Many of the GM series I work on today are 20-30+ years old and still perform beautifully, especially if well-maintained. I know the attention to detail paid to the GM line is indicative of Yanmar’s philosophy throughout the line. Yanmar has built its own empire over the last 100 years, and it continues to improve its design, efficiency and reliability. While some may consider the GM series obsolete, they are out there doing the job and owners need to know how they tick.

In future issues of Practical Sailor, I’ll be back to discuss the care and feeding of your diesel auxiliary, which, like a good dog, only wants to please. Your job is to treat it right.

I think I have solved the dissolving air filter problem K&N makes several styles of clamp on cylindrical air filters that end in a short length of essentially rubber hose, that can be clamped around the end of the nozzle of the air filter housing with a hose clamp. A K&N RD–0450 fit on mine. If I recall correctly it cost about $50 from Amazon, but there are many sources. I left the oil breather setup as Yanmar designed it. I orient the nozzle vertically so that none of the oil can drip into the filter. And the filter is easily seen to monitor for the need to replace it. I’d love to send a photo of the filter on the engine, but the boat is put away right now – not handy. Works fine. I’ve put several hundred hours on the engine since installing the K&N.

What Yanmar engine do you use the K&N RD–0450?

Great article! Thank you

Love it! Great article. I just picked up a used 3GM30F for a repower in my Ericson 35, so this is extremely pertinent.

A really thoughtful article, with new information and explanations. I repowered to a 3YM20 in my Atlantic City Catboat, and it is a “rock crusher”. Have had it since new about 15 years now. Routine maintenance each season, and it has never failed me. I was aware of the exhaust elbow issue, so I did replace it-but found it to be in fine condition anyway. I think following Yanmar’s operation guidelines regarding high max revs for 10 minutes at the end of a longer motoring session does extend the life of the entire exhaust system. This engine does have glow plugs, which might be helpful below 50 F, but I have never had to use them. Engine starts every time in a nano-second. Highly recommend this engine. It is quiet, and no vibe when above idle. Design has no dissimilar metals, so no anodes required. Thanks for the info!!

This is one of the best series to come to PS!

Will you be continuing with other engines like Westerbeke? BTW, I had no idea Yanmars were so well designed.

A second on the K&N line of filters! Found a height & circumference that would work for my 2GM & ‘modified’ the rubber capped side; positioned over the intake port it works wonderfully! No more disappearing foam & easy to clean & re-oil the filter. Wish I had not lost the box or I would post the K&N model #… IF anybody has the info PLEASE post it up!!

As I said, a K&N RD-0450 fit clamped on the air cleaner nozzle of my 3HM34F Yanmar. And I’m pretty sure the air cleaner housings are universal among the smaller older Yanmars. Plus, when I was researching a K&N filter, the staff at K&N was helpful in identifying which of their clamp-on filters would fit. Hope this helps.

Great Article. I rebuilt a 3QM30 in 2015 for under $2k. The QMs are even more a beast weighing almost twice that of the GM equivalent and loud as hell but sounds great when sailing… See svjohannarose dot blogspot dot com/search/label/EngineWork.

Thanks for your informative article. I have a 1984 3GMF. What do you know about the number of hours before overhaul for a well-maintained engine?

Also, do you have a list of the components that are likely to fail so should be replaced? I replaced the gear cover gasket and understand that is a common wear item.

Thanks, Tom

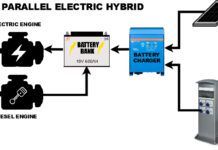

Very interesting article! I’m looking forward to your follow-up article on routine maintenance. I’d appreciate it you would expand it to cover larger Yanmar’s. I have twin 100 HP Turbo Yanmar’s (YJH3-HTE) on my PDQ Power Catamaran.