A mixture of old and new, of reality and hype, seems to characterize the Jeanneau company and its boats. A bit of old-fashioned attention to detail; a bit of high-tech stamp-em-out production. A bit of old-fashioned engineering; a bit of “to hell with tradition, let’s make this boat different.”

To most Americans, the Jeanneau boats seem to have appeared suddenly, but the company has been around since l956. Aggressive entry into the American market resulted when Lear Siegler bought Jeanneau and the other Bangor Punta boat companies (Cal, O’Day, Ranger) in 1983.

Like most of the Jeanneaus, the Arcadia (pronounced “Are-caw-dee-yah”) is rare in America—only a few were imported—but, also like most of the Jeanneaus, the total production run is incredible—the factory popped out 600 completed boats in the Arcadia’s first two years. The only American company that could even aspire to such numbers in a 30-footer is Catalina, and they produce a miniscule number of models compared to Jeanneau.

A notable thing about Jeanneau is the diversity of designers—almost all “big names,” at least in Europe, and almost all with grand-prix racing credentials: Guy Dumas, Doug Peterson, Philippe Briand, Jacques Fauroux, the Joubert/Nivelt team.

The designer of the Arcadia is Tony Castro, new to Americans but an established designer in Europe. Of Portuguese descent, Castro began his work with Ron Holland in Ireland, then set up his own shop in 1981 and achieved success designing successful IOR racing machines. Now a British citizen, he has two other designs in production at Jeanneau, and a third—an IOR half-tonner—scheduled for production soon.

The design of the Arcadia is not IOR. We would call it “moderate modern,” of relatively light displacement and shallow hull, with a high aspect ratio keel, separated spade rudder, and beamy hull.

Her appearance is, well, “European.” The flat sheer, a doghouse that slopes forward into the foredeck, long black windows (you can’t call them “ports”), and blunt ends make up that “European” look which is decidedly—almost blatantly—nontraditional.

“Thoroughly modern” is a term that appears several times in Jeanneau’s advertising blurbs.

Construction

In contrast to the boat’s image, the construction of the Arcadia is anything but high-tech.

The hull is standard hand laid fiberglass mat and roving; the deck is standard hand laid fiberglass with balsa core in spots. The balsa-core “spots” seemed to be less extensive than normal (we couldn’t examine much of the deck molding because of the interior ceiling liner), but the deck was stiff enough underfoot. The deck hardware we could examine was through-bolted with big washers, but there were no backing plates on anything.

The hull-to-deck joint typifies the construction of the boat. The joint appears to be a standard inward-turning flange on the hull, on which the deck molding rests. Then 1/4″ stainless bolts are set through an aluminum toerail as well as the deck and the hull flange.

Pretty normal so far, but Jeanneau finishes off the joint on the inside by laying a thick layer of fiberglass over everything—from the hull, over the seam, covering the bolts, onto the deck. It looks strong—a good way to build a decent hull-to-deck joint on a fast moving production line. The reservation we have about it is in repairs—if the joint is damaged, it will be tough to examine thoroughly and tough to fix. Similarly, the joint should never leak, but if it does, tracking down the source will be nearly impossible.

Generally, the glasswork and gelcoat look good; the two hulls we examined were smooth and fair.

The boat’s strength and stiffness probably come from Jeanneau’s practice of bonding everything to everything else. Not only are the athwartship bulkheads bonded to the hull and deck with fiberglass tape, but cabinet fronts are bonded to hull and bulkheads, cabinet sides are bonded to fronts and bulkheads, the head door frame is bonded to the engine box frame which is bonded to the hull and to the cockpit, and so on. The whole interior is obviously prefabricated in typical production line fashion, but we’ve never seen another production boat in which the interior parts were so much fiberglassed to each other and to the hull. It seems like a good lowtech method of acquiring stiffness without skeleton framing or coring the hull.

Like many of the Jeanneaus, the Arcadia comes with either a centerboard or an external keel—about 70% having been keel models. The keel is unusual in two respects. First, rather than lead, it’s iron, coated with fiberglass to prevent corrosion. Second, the keelbolts are not vertical and on centerline in the normal fashion. Instead, they are set in pairs, angled from the sides of the keel inward so that, inside the hull, the bolts, were they long enough, would converge and touch. Further, once the keel is bolted on, a heavy layer of fiberglass is laid in the bilge to fully cover the bolts. As with the hull-to-deck joint, this looks strong and leak proof, but again we would be concerned about the difficulty of repairs and finding leaks following a hard grounding. The keel that we examined was fair and well finished. We did not inspect a centerboard model.

The spade rudder is supported by a small skeg; the one we saw was well finished except for a rough trailing edge. Tiller steering is standard on the Arcadia, but both boats we examined had the optional Plastimo wheel steering, with a “European size” wheel, about 24″ diameter. Most Americans like a much bigger wheel; unfortunately a larger one could not be fitted without major modifications to the cockpit seats.

The rig generally looks to be pretty standard issue—masthead rigged sloop, with upper and aftlower shrouds and a “baby stay” forward. The boat we examined had double spreaders, whereas the company literature and photos show a single-spreader mast. The company does advertise an optional tall “lake” rig, but this is designed only for European inland lakes and would be unsuitable for coastal, Great Lakes, or offshore sailing. None were imported into the U.S.

The upper shroud chainplates are anchored on a transverse overhead frame which begins at a settee bulkhead on the hull and then extends up over the cabin and down to the hull on the opposite side, with a compression post in the middle of the cabin under the mast. The frame is bonded to the hull and deck and should provide adequate strength and mast support. The lower shroud chainplates are anchored to a similar frame, bonded only to the hull and side decks.

A final note on the Jeanneau’s construction. We asked the dealer who was showing us one of the Arcadias to pick out one thing that made the Jeanneau different from the three American brands he also handles. “They are dry,” he said. “I don’t know how they do it, but they just don’t leak, either from the top of the deck downward or from the bottom of the hull upward.” From a dealer who has sponged out a lot of bilges before bringing customers on board, those are words of praise.

Handling Under Power

The two Arcadias that we looked at had two-banger diesels—one a Yanmar, the other a Volvo (production line changes, again). Sales literature lists an outboard version—thankfully no such monster is likely to be imported—and a version with either a one or a two cylinder Yanmar. For a 6000+ pound boat, we would consider the one cylinder very marginal and recommend the two cylinder, along with the optional folding prop.

The engine installation is well done (stringers and beds bonded to everything in sight) with soundproofing on the compartment walls, a waterlift muffler, and a seven gallon fuel tank. There is good accessibility to the engine through the aft cabin and through the removable companionway, except that the dipstick on the Yanmar is hard to get at.

Two details impressed us. The engine compartment has a small electric bilge pump as standard equipment in the sump below the prop shaft’s packing gland—one place that is likely to have water. And, in the front of the companionway steps that open onto the engine, there’s a 2″ hole with a plastic cover, the function of which baffled not only us but also the first person who showed us the boat. Finally, the dealer explained its purpose: in the event of an engine room fire, pull the plastic cover, insert the working end of a fire extinguisher, and discharge it. Eminently more practical than pulling off the companionway steps and feeding more oxygen to the flames.

Under power with the folding prop, the boat handled satisfactorily, backing where we wanted to back it, with adequate power in forward and reverse. Visibility from behind the wheel is decent, but there is no comfortable place to sit aft and the wheel is too small to reach from the sidedeck. The engine had no more vibration than you’d expect from a two-cylinder diesel and was a bit quieter than other boats, probably because of the insulation in the engine compartment.

Handling Under Sail

We were able to sail the Arcadia for only about an hour; unfortunately, we have too few reader responses to make many valid judgements about the Arcadia’s performance under a variety of conditions (most of our owner’s responses are based on a single season’s sailing, or less).

In our limited experience, we found that she went to weather, reached, and ran very much like other contemporary racer-cruisers. She pounded a bit in a short chop, as you might expect from her shallow hull design, but we saw no other bad habits. (Her sails are from a small French loft, “Ton,” and are adequate. Racers will want to get better.)

Her PHRF rating of 150 suggests that overall performance under sail is about midway between older racer-cruisers like the Pearson 30 or Tartan 30 and the newer racer-cruisers like the Santana 30/30 or the S2 9.1. We were hoping that—as a Tony Castro design—she might be a rocketship, but she’s not. She will be a fast cruiser, and an owner will be able to race her under PHRF.

Deck Layout

With inboard shrouds, wide sidedecks, and the sloping cabin top, the Arcadia is easy to move around on and to work under sail. We only noted two problems: first, the foredeck becomes very narrow—an impediment to easy foresail and anchor handling that is all too common in modern designs. Second, the cockpit was uncomfortable—the seats a little too narrow, the backs too vertical, and the footwell maybe a little too deep. We also had trouble reaching the small wheel from either the windward or leeward sidedecks where you would normally sit while racing.

Deck fittings are generally good quality and adequately sized, with everything necessary to race the boat except spinnaker gear coming as standard equipment. We did feel that the designer had not quite thought through crew positions for working the boat—what should be done at the mast, what from the cockpit—surprising for a contemporary IOR designer who must attend to those details. Most owners will probably rearrange things after a season’s experience.

The non-skid is average, but there are some nice details on deck such as the twin bow rollers for anchor handling, the sturdy latch on the anchor locker, and the large mooring cleats. There’s a space at the back of the cockpit for life raft stowage and for propane bottles, and a stowage bracket for a horseshoe buoy built into the stern pulpit. The stern pulpit opens up to a folding stainless ladder.

Belowdecks

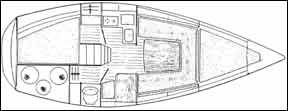

It is “downstairs” that Jeanneau really spits in the eye of tradition—not just in the Arcadia but in most of their models. Most obvious is the layout, with the Arcadia’s head and the owner’s double-berth cabin packed into the rear third of the boat, partly under the cockpit. Both head and owner’s cabin are a little cramped, but for a smallish 30-footer, it’s surprising they are possible at all.

The rest of the cabin is wide open, with a small galley and navigation table opposite each other, then settee berths on either side of a fold-up centerline table, then a crawl-in forward berth.

We noted three drawbacks. First, the forward Vberth is too short for adults. Second, anyone over 5′ 8″ or so cannot sit upright on the settee berths without banging the overhead. Third, the standing headroom at the aft end of the cabin disappears as you walk forward under the sloping deckhouse.

This last item we really find hard to understand, since headroom is something most people are looking for, and the only apparent reason not to have it in a 30-footer is to satisfy the “style” of the sloping deck house. (There is a bit of a weight saving that might be important in a racer but hardly valuable in the Arcadia.) Oddly, the same headroom problem exists even in the 34′ Jeanneau Sunrise that we looked at.

The interior of the Arcadia is all woody and undoubtedly one of the strong selling points at boat shows. Teak-faced plywood is all over the place. We thought the veneer work was good for production line work, especially where the veneer covered the plywood edges—for example in the window cutouts. The wood has a light coating of varnish, even inside lockers and drawers. The overhead has a soft vinyl covering that looks a little better than bare fiberglass. Inside hardware—like hinges and latches—is noticeably better than on the usual American production boat.

A strange detail is the manual bilge pump whose handle sticks out of the side of the chart table into the middle of the cabin.

Oddly, the boats we inspected were not “Americanized.” Most owners would likely want shore power, but this is not a company option—it will have to be installed by the owner or dealer. The galley stove comes with hook-ups for butane which will have to be converted to propane. And many Americans looking at a 30-footer might expect a shower, which will be difficult to install on this boat.

Conclusions

Overall the Jeanneau Arcadia surprised us. We were expecting a boat comparable in quality to mid-line American production boats; we found the Jeanneau to be somewhat better in construction and in many details. Being fond of tradition, we have a problem with the style of most of the Jeanneaus, including the Arcadia, but ultimately style is a tenuous criticism of a boat, unless it is truly ugly.