The Pacific Seacraft Flicka has perhaps received more “press” in the last few years than any other sailboat, certainly more than any production boat her “size.” Publicity does not necessarily make a boat good but it sure does create interest.

The Flicka is unique. There are no other production boats like her and only a few, such as the Falmouth Cutter and the Stone Horse, that offer the Flicka’s combination of traditional (or quasi-traditional) styling and heavy displacement in a small cruising yacht.

As the number of Flickas built by Pacific Seacraft passed 300 plus an indeterminate number built by amateurs early in its history, the boat seems to have become almost a cult object. High priced, distinctive, relatively rare but with wide geographical distribution and easily recognized, the Flicka invariably attracts attention and seems to stimulate extraordinary pride of ownership, The owners we talked to in preparing this evaluation all seem to be articulate, savvy, and involved. Moreover, they all show an uncommon fondness for their boats.

The Flicka was designed by Bruce Bingham, who was known as an illustrator, especially for his popular Sailor’s Sketchbook in Sail. Originally the Flicka was intended for amateur construction, the plans available from Bingham. She was designed to be a cruising boat within both the means and the level of skill of the builder who would start from scratch. Later the plans were picked up by a builder who produced the boat in kit form, a short lived operation, as was another attempt to produce the boat in ferro-cement.

Pacific Seacraft acquired the molds in 1978 and, with only minor changes, the boat as built by Seacraft remained the same until 1983, when a new deck mold was tooled to replace the worn-out original. A number of the modifications made early in 1983 are described throughout this evaluation.

Seacraft is a modest sized builder which has specialized in heavier displacement boats. The first boat in the Seacraft line was a 25-footer, followed by the 31′ Mariah, the Flicka, the Orion 27, and most recently the Crealock 37.

Seacraft has 22 dealers nationwide but concentrated on the coasts. Apparently the firm was able to survive the hard times that have befallen some if its brethren, giving credence to the axiom that to succeed a boatbuilder should produce an expensive boat to quality standards that appeals to a limited number of enthusiastic buyers.

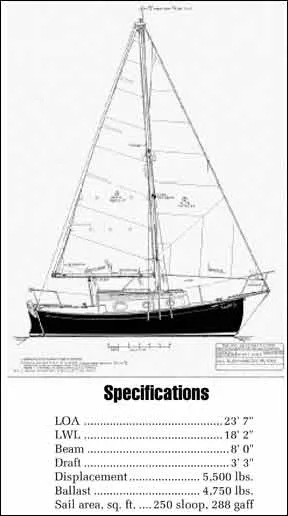

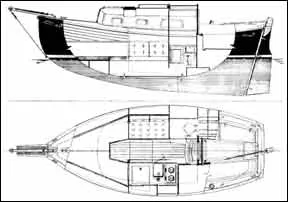

The hull of the Flicka is “traditional” with slack bilges, a full keel, a sweeping shear accented with cove stripe and scrollwork, and bowsprit over a bobbed stem profile. In all, the Flicka is not an actual replica, but she does fulfill most sailors’ idea of what a pocket-sized classic boat should look like whether or not they are turned on to that idea.

The new price of the Flicka in the early ’80s ranged from about $13,000 for a basic kit for amateur completion to $36,000 for a “deluxe” version, with $25,000 a realistic figure for a well-appointed standard model. This was a high tab for a boat barely 18′ long on the waterline, 20′ on deck (LOD), and less than 24′ overall with appendages. With that high priced package you got a roomy, heavy and well-built boat that appealed to many sailors’ dreams if not to their pocketbooks.

Construction

The Flicka looks well built even to an untrained eye. And to the trained eye that impression is not deceiving. This is a boat that should be fully capable of making offshore passages. The basic question any buyer must ask is whether he is willing to pay (in money and performance) for this capability for the far less rigorous cruising on Lake Mead or Chesapeake Bay, to Catalina Island, or up and down the

The hull of the Flicka is a solid fiberglass laminate to a layup schedule adequate for most 30-footers of moderate displacement.

The deck has a plywood core rather than the balsa core common in production boats. In a boat of this displacement-length ratio the heavier plywood reduces stability but probably only marginally. Its virtue is that installation of add-on deck hardware is easier.

The hull-to-deck joint is done in a manner Practical Sailor strongly advocates: the hull has an inward flange on which the deck molding fits, bonded with a semi-rigid polyurethane adhesive/sealant and through bolted with 1/4″ stainless steel bolts on 4″ centers. These bolts also secure the standard aluminum rail extrusion; on boats with the optional teak caprail in lieu of the aluminum, the bolts pass through the fiberglass, and the caprail is then fastened with selftapping screws. As the rail sits atop a 1/2″ riser, water cannot puddle at the joint. We have heard no reports of any hull-to-deck joint failure in a production Flicka.

The interior of the boat uses a molded hull liner that is tab bonded to the hull. Given the ruggedness of the hull laminate, we doubt if this stiffening adds much to the hull itself, but it does make the relatively thin laminate of the liner feel solid under foot.

One of the more serious questions we have about the engineering of the Flicka is the under-deck mast support. Reflecting the quest for a completely open interior, the design incorporates a fiberglass/wood composite beam under the cabin house roof which transfers the mast stresses through the house sides to the underdeck bulkheads. Apparently these bulkheads are not bonded to the hull itself, only to the liner.

The builder defends this construction, claiming that it will support over 8,000 lbs (more than the Flicka’s displacement). In addition, beginning in 1983, a turned oak handhold post was added between the mast support beam and cabin sole, which further increases the strength of the mast support system.

Cabinetry, detailing, and finish are top quality for a production boat. However, keep in mind that the basic interior component is a fiberglass molding. Functionally the ease of keeping a molded liner clean has much to recommend it; aesthetically the sterility of the gelcoat may offend some tastes.

A few other specific construction details deserve note:

• The hardware on the Flicka is generally excellent, whether it is the standard or the optional cast bronze package, provided your taste allows for a mixture of traditional and modern. Since weight has not been a factor, most of the fittings are rugged, even massive. All through hull fittings are fitted with seacocks. Particularly impressive is the tabernacle mast step, a contrast with the flimsy sheet steel versions on cheaper boats. A notable exception to this endorsement are a pair of inadequate forward chocks.

• The scribed “planking seams” in the fiberglass topsides as well as the scrollwork are especially well done. However, any owner of a wood boat who has spent untold hours fairing topsides to get rid of real seams has to wonder at anyone’s purposely delineating phony seams in fiberglass.

• There is a removable section of cockpit sole over the engine compartment that gives superb access for servicing the engine and permits its installation or removal without tearing up the interior. It is a feature many boats with under-cockpit engines should envy given the chronic inaccessibility of such installations. Access to the Flicka’s engine from the cabin is no better than that on most boats even for routinely checking the oil level.

• External chainplates eliminate a common source of through-deck leaks but at the expense of exposing the chainplates to damage.

• There is good access to the underside of the deck and coaming for installation of deck hardware. The headliner in the cabin is zippered vinyl.

• Anyone with a modern boat with its vestigal bilge sump has to appreciate the Flicka’s deep sump in the after end of the keel.

• The ballast (1,750 lbs of lead) is encapsulated in the molded hull, risking more structural damage in a hard grounding than exposed ballast but eliminating possible leaking around keel bolts.

Handling Under Sail

In an era that has brought sailors such hot little boats as the Moors 24, the Santa Cruz 27, and the J/24, any talk about the performance of a boat with three times their displacement-length ratio has to be in purely relative terms. In drifting conditions the Flicka simply has too much weight and too much wetted surface area to accelerate. Add some choppiness to the sea and she seems to take forever to get under way.

When the wind gets up to 10 knots or so, the Flicka begins to perk up, but then only if sea conditions remain moderate. With the wind rising above 10 or 12 knots the Flicka becomes an increasingly able sailer.

However, she is initially a very tender boat and is quick to assume a 15 degree angle of heel, in contrast to most lighter, shallower, flatter boats that carry less sail but accelerate out from under a puff before they heel.

In winds over 15 knots the Flicka feels like much more boat than her short length would suggest. As she heels her stability increases reassuringly. Her movement through the water is firmer and she tracks remarkably well, a long lost virtue in an age of boats with fin keels and spade rudders, Owners unanimously applaud her ability to sail herself for long stretches even when they change her trim by going forward or below.

Practical Sailor suggests those looking at—and reading about—the Flicka discount tales of fast passages. While it is certainly true that the boat is capable of good speed under optimum conditions, she is not a boat that should generate unduly optimistic expectations. In short, there may be a lot of reasons to own a Flicka, but speed is not one of them.

One mitigating factor is that performance consists not only of speed but also ease of handling, stability, steadiness, and even comfort. In this respect, the Flicka may not go fast but she should be pleasant enough to sail that getting there fast may not be important.

The Flicka comes with two alternative rigs, the standard masthead marconi sloop and the optional gaff-rigged cutter. Most of the boats have been sold as sloops. The gaff cutter is a more “shippy” looking rig, but for good reasons most modern sailors will forego a gaff mainsail.

If you regularly sail in windy or squally conditions, you might want to consider a staysail for the sloop rig. However, for a 20′ boat an inventory of mainsail fitted with slab reefing, a working jib, and a genoa with 130% to 150% overlap should be adequate. For added performance the next sail to consider is a spinnaker and, if offshore passages are contemplated, a storm jib.

Handling Under Power

Any observations about handling under power raise the question of inboard versus outboard power. In fact, this may be the most crucial issue a potential Flicka owner faces. In making the decision, start with an observation: at a cruising displacement of over 5,000 lbs, the Flicka is at the upper limit for outboard auxiliary power. Then move to a second observation: small one-cylinder diesel engines such as the Yanmar and BMW fit readily into the Flicka, albeit at the expense of some valuable space under the cockpit sole.

Without going into all the pros and cons of one type of power versus another, we suggest installation of a diesel inboard either as original equipment or as soon after purchase as feasible. The Flicka is a boat that seems to beg for inboard power (most small boats do not); she has the space, and weight is not critical. Moreover, cost should not be critical either. Inboard power adds about 10% to the cost of the boat with outboard power, a small percentage of an expensive package. Much of the additional cost is apt to be recoverable at resale whereas the depreciation on an outboard in five years virtually amounts to its original value.

Deck Layout

Any discussion of the livability of the Flicka should be prefaced by a reminder that above decks this is a crowded, cluttered 20 footer and below decks this is a boat with the space of a 26 footer. The Flicka is a boat with enough space below for one couple to live aboard and yet small enough topside for them to handle easily.

Nowhere is the small size of the Flicka more apparent than on deck and in her cockpit. The short cockpit (a seat length of barely over 5′, too short to stretch out for a nap), a high cabin house, sidedecks too narrow to walk on to windward with the boat heeled and always obstructed by shrouds, the awkwardness of a bowsprit, and lifelines that interfere with jib sheet winching are all indicative of the crowded deck plan.

The stern pulpit is an attractive option. However, it makes manual control of a transom-mounted outboard difficult. The pulpit incorporates the mainsheet traveler although the lead for close sheeting is poor. In 1983 an optional roller bearing traveler arrangement which spans the bridge was offered, and it provides a much better lead for close sheeting, at the expense of a certain amount of living space in the cockpit.

For outboard powered Flickas there is a lidded box that permits stowage of the fuel tank at the after end of the cockpit, a sensible and safe feature. For those owners who want propane and have inboard power, this same space fitted with a sealed box and through-transom vents would make a suitable place for gas bottles.

At the other end of the cockpit, the lack of a bridgedeck or high sill is, in our opinion, decidedly un-seamanlike. The Flicka should have at least semi-permanent means of keeping water in a flooded cockpit from going below. One of the 1983 changes was the addition of a bridgedeck.

If we owned a Flicka we would run all halyards (plus a jib downhaul) aft to the cockpit on the cabin top. We would not rig a fixed staysail stay, and we would certainly not use a clubfooted staysail. The boom should have a permanent vang.

Belowdecks

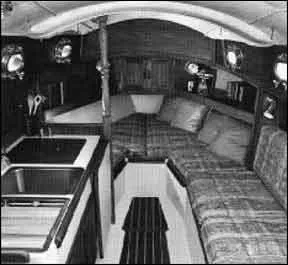

The builder has made every effort to keep the interior of the Flicka open and unobstructed from the companionway to the chain locker, a noble endeavor that gives an impression of spaciousness rivaling that of 30 footers. Headroom is 5′ 11″ for the length of the cabin (find that in another boat-shaped 20 footer!). Better yet, height is retained over the galley counter, the settee berth, and the after section of the vee berths. Flicka’s high topsides permit outboard bookshelves and galley lockers, stowage under the deck over the vee berths, and headroom over the quarterberth.

Two notable features of the interior are conspicuous as soon as the initial impression wears off. There is no enclosed head in pre-1983 models, and there is no sleeping privacy. How important these factors are is purely a matter of individual taste and priorities. For a cruising couple a four-berth layout is a waste of space. The manufacturer, taking this into account, made space for the enclosed head offered in 1983 by shortening the starboard settee berth from 6′ 5″ down to 4′ 2″.

Incidentally, this observation about berths is not meant to imply any special deficiency in the Flicka. It is true of too many boats on the market. They are built for a boat buying public that seems to think the number of berths is almost as important as whether the boat will float.

The absence of an enclosed head in a small yacht of the proportions of a Flicka requires a conscious decision from any potential owner. The small space between the vee berths is designed to hold a self-contained head. A “privacy curtain” that slides across the cabin gives a modicum of respectability. Of course, its use is discouraged when anyone is sleeping forward. One owner solves this by lugging the head to the after end of the cockpit at night and encloses the cockpit with a tent, thus creating a privy or outhouse that boasts perfect ventilation. We hesitate to suggest his lugging it another few inches aft.

Less enterprising owners could consider installing a conventional marine toilet plus a holding tank under the vee berths. If sailing is done in waters where a through-hull fitting and diverter valve are permitted, then such a system is far more worthwhile than any self-contained system. Such a unit should make sharing your bed with the head as palatable as it will ever be.

Frankly, the lack of an enclosed head in a boat that otherwise can boast of being a miniature yacht is the most serious drawback to her interior, surplus berths notwithstanding.

Virtually every owner we talked with has added stowage space one way or another. Some have done it by removing the fiberglass bins that fit into the scuttles under the berths, others enlarge the shelves behind the settee berth and over the forward berths and others cut openings through the liner to give access to unused space.

Other modifications owners report having done include fitting the boat with a gimballed stove, adding fresh water tankage (20 gals standard), installing a third battery and/or moving them forward to help overcome a tendency for the Flicka to trim down by her stern, and fitting the cockpit with a companionway dodger.

One feature that does not seem to need any improvement is ventilation. The Flicka has an uncommonly airy interior, although we would add an opening port in the cockpit seat riser for the quarterberth. Her vertical after bulkhead means that a hatchboard can be left out for air without rain getting into the cabin.

Anyone considering the Flicka should ask Pacific Seacraft for a copy of the articles written by Bruce Bingham and Katy Burke on the changes they made to their Sabrina while living aboard and cruising extensively for more than two years.

Conclusions

Buyers put off by the price of the Flicka should consider the fact that this is a 20′ boat with the weight and space of a 26- to 28-footer of more modern proportions. That still may not put her high all-up price tag in crystal clear perspective. It shouldn’t. The Flicka is still an extremely expensive boat. She still has a waterline length of merely 15′, true accommodations for two, a too cozy cockpit, and a lot of sail area and rigging not found on more conventional contemporary boats. Nor does she have the performance to rival more modern designs. (One owner reports a PHRF rating for his Flicka of about 300 seconds per mile, a figure that drops her off the handicap scale of most base rating lists we’ve seen.)

At the same time the Flicka is a quality package that should take a singlehander or couple anywhere they might wish to sail her. There are not many production boats anywhere near her size and price that can make that claim.

The faults with the Flicka have to be weighed against her virtues as is the case with choosing any boat. Fortunately, though, her faults are the type that can be readily seen; they are not the invisible ones of structure, handling, or engineering so typical of other production boats. Similarly her virtues are traditional and time tested, She is built by a firm to whom the owners give high marks for interest and cooperation and the Flickas on the used boat market have maintained their value better than the average production boat. At the bottom line is a boat with much to recommend her.