Like a lot of people, our first recollection of the Albin Vega was an advertisement in the sailing magazines. In the early 1970s, a time when California production coastal cruisers dominated the American market, this little Swedish import was hyped as a serious offshore cruiser. Our reaction was, “What has this boat got that the others don’t?”

The ad photo showed the Vega backlit by a late afternoon sun, sailing out to sea. The copy touted it as a “…four berth diesel cruiser built of reinforced fiberglass…” that “…sails in her own class and holds the record for the fastest Atlantic crossing.” Other noteworthy gear mentioned was the single lever, variable pitch prop, dodger and stainless steel sink with fresh and sea water foot pumps. One surmised from the above that the Vega was light, fast, seaworthy and cruisable. Seventeen years later, it’s easier to put the Vega in perspective. The boat comes close to its billing, but it’s not without its flaws.

Design and Construction

We were not able to confirm the exact dates of production, but we do know that the boat was designed in 1966. Responses to our Boat Owner’s Questionnaire range from hull #249, built in 1968, to hull #3361 built in 1979.

Sailed as a one-design in Europe, the Vega made inroads into the American sailing scene as well. They are still commonly sighted. By any standard, the Vega was a successful design.

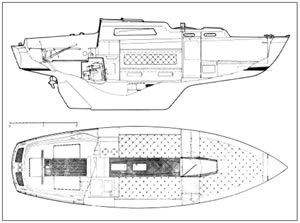

Designed by Per Brohall, the Vega has a narrow, easily driven hull. Beam is just eight feet, a foot or more narrower than similarly sized boats of the late 1980s. The hull is shallow, with a large cutaway forward of the so-called “full keel.” The rudder is attached but there is no aperture for the propeller.

The shaft exits the deadwood just above the rudder, under the counter. More on this later.

In profile, the sheer is reversed. This gives the boat an odd look, though certainly not an unpleasant one. Reverse sheer is used mainly on smaller boats to increase interior space. Also, the tumblehome of the topsides (the middle of the hull above the waterline is wider than at the toerail) causes the hull, rather than the stronger hull-deck joint and rail, to take the brunt of bumpings with pilings.

A teak rubrail could be through-bolted along the most exposed area, which would protect a new paint job but which might be difficult to make aesthetically pleasing. A rubrail should follow, to some extent, the line of the sheer, and on a boat with reverse sheer, this would produce a very strange looking rubrail! Some experimentation on paper would be wise.

The hull and deck are built of fiberglass—chopped strand mat and woven roving bonded with polyester resin—with coring in the deck and coachroof. Company literature asserted that the hulls are 3/8″ thick

at the toerail, increasing to 1″ at the base of the keel. There is ample evidence, however, that some panels, such as the cabin sides, are too thin. On one boat we sailed, they oilcanned easily by pressing the hands against them. Also, the deck did not feel as solid as the advertisements would have us believe—perhaps we were witnessing deck delamination.

Excessive gel coat cracking is the only obvious result, but it is not comforting to feel a panel give.

The boat has proven itself offshore, but this does not necessarily mean the structure is well-engineered. One reader wrote: “Hull suspiciously thin. The Vega is ocean rated (but) my only question is how much can it take.”

John Neal, who sailed 14,000 miles throughout the South Pacific on a Vega in the mid-1970s and wrote about his adventures in a book titled Log of the Mahina, called the Vega sound, noting that his had survived collisions with coral heads.

Neal, however, also mentioned a problem we noticed, that of deck compression from the deckstepped mast. Toward the end of his cruise, the main load-bearing bulkhead was actually warping. He wrote: “Upon close inspection, I found that one of the two supports on the main bulkhead had sheared its glue bond, breaking a three-eighths-inch stainless steel bolt, and had been forced through the fiberglass cabin sole. Also, the main port bulkhead had started to warp seriously at the top.”

This problem, fortunately, is less common than it was in early fiberglass boats. So often we hear that older fiberglass boats were built much more strongly that today’s. Well, it ain’t necessarly so. The buyer of a Vega wishing to sail it hard should give some thought to solving this problem. Gluing and screwing plywood to the bulkhead for double thickness would help, as would replacing the overhead beams with larger ones. Of equal importance is transmitting the load from the sole to the hull. This would mean fiberglassing a support between the sole and hull— not an easy job, but a necessary one. Care should be taken not to create hard spots in the hull. The procedure for fitting bulkheads is covered in many books and involves cutting foam wedges to fit between the wood and hull, the joint amply covered with successively larger widths of fiberglass tape.

The hull-to-deck joint is an internal flange with pliant caulking (“2 pack rubber”), fastened through with 5/16″ stainless steel bolts every five inches. None of our readers have reported leaking.

Some owners noted the weakness of the rudder. Neal lost his while hove to. After making repairs, he then hove to with slack in the tiller lashings, which worked.

Performance Under Sail

The Vega is a fine little sailer whose greatest virtue is manageability in a wide range of conditions. Nearly all owners remark how well the boat is balanced. We, too, noticed this trait immediately, admiring the light helm and good tracking.

Light air performance is criticized by numerous owners. When the wind blows over about 15 knots, they say, the boat really comes alive. We did not think the boat we sailed suffered terribly in lower wind speeds, but compared to a more contemporary coastal design with fin keel and larger rig, the Vega would undoubtedly come up short. This is an acceptable compromise for an offshore boat. Many owners say they can keep sailing when others are heading in, adding that the boat remains dry even in rough conditions.

As one would expect from her round bilges and relatively shallow keel, the Vega is initially a mite tender, heeling easily to about 15 degrees. Thereafter, with her shoulder buried, she becomes quite stiff. Again, this is not an undesirable trait for an offshore cruiser.

All in all, the Vega is a pleasure to steer. Unlike modern boats with spade rudders, that tend to stall when overcanvassed, the Vega remains under control at all times. We find that a most comforting characteristic—indeed, a prerequisite for safe, comfortable cruising.

Performance Under Power

The early Vegas were equipped with Albin 022 13 hp or Volvo MB10A 15 hp gas engines, later replaced with Volvo diesels, including the 10 hp MD6A and 13 hp MD7A. Some early Vegas did not have trans- missions, using the Combi variable pitch prop instead. An owner of a 1976 model wrote that by the time Albin built his boat, a transmission had been added. The variable pitch prop was retained, using a single lever control without clutch. “This is an interesting piece of engineering,” he wrote, “but hell to repair.”

The variable pitch system is far superior to conventional propellers in terms of efficiency. However, it does have drawbacks, principally the grease seals that may leak. A number of readers wrote that parts for the Combi unit, as well as mechanics familiar with it, are hard to find.

Most owners report forward power as good, most saying she’ll cruise at six knots. A few owners of the 10-hp diesel said the boat was slightly underpowered, which probably explains why later boats were fitted with the 13-hp model.

Reverse is another story. The value of the variable pitch Combi drive with 1.42:1 reduction gear, which provides greater power backing down, is mitigated by the fact that the propeller is situated aft of the rudder. This makes the boat a devil to steer in reverse. Almost every owner reported difficulty with the boat in reverse, noting that manuevering in tight quarters requires extra vigilance.

On the plus side, the Volvo engines rate high in reliability. Accessibility is better than average. The real problems with the power train lie in maintaining the Combi drive, which is an asset if working properly and a liability if allowed to deteriorate.

The Interior

The Vega is not a large 27-footer by today’s standards, yet its layout is quite serviceable for a couple despite the fact that headroom is just 5′ 10″ (actually 5′ 7″ in the boat we measured) in the main cabin. As the British designer Uffa Fox once said, “If you want to stand up, go on deck.”

The straightforward layout includes V-berths forward (6′ 0″ starboard, 6′ 6″ port), a partially enclosed head compartment forward of the main bulkhead, 6′ 1″ and 6′ 6″ settees in the main cabin, and a galley split port and starboard by the companionway. There is ample stowage behind the seatbacks, under the settees and in various galley bins.

The dinette table removes for stowing, or for mounting in the cockpit; the two legs set in sockets sunk into the cabin sole and cockpit floor. The main shortcoming of the plan is that the toilet is open to the V-berths, which is why this boat is best suited to a couple or small family, or at the least those of intimate relations!

Woodwork is hand-rubbed mahogany, which is quite attractive if maintained properly. The overhead has a fiberglass liner but the cabin and hull sides do not; the latter are covered with a foambacked perforated vinyl. The cabin sole is fiberglass, which transmits cold and noise—best to cover with a moisture-resistant carpet.

All windows are fixed, which is typical of boats built in far northern climates. The rubber gaskets are a bit of a worry, as the material can degrade over time, permitting leaks.

An innovative ventilation system helps keep the interior dry and mildew at bay. Air is introduced through a ventilator in the forward cabin and exhausted via the mast and a cockpit ventilator.

Conclusion

The Albin Vega is an interesting boat, one that in many respects was ahead of its time. Except for the limitations mentioned, construction was essentially sound. The design is superb. We like the variable pitch propeller despite the extra maintenance required. Placing it in an aperture in front of the rudder would help performance in reverse a great deal, but this would have required a deeper hull form and thereby change the entire concept of the boat. Considering that sailboats spend very little time going backwards, we think Brohall made a good decision.

The base price of the Vega in 1977 was about $21,000, with a good list of standard gear. That boat today sells for about $16,000. Depending on condition, you could buy one for less. Any way you cut it, the Vega represents a good value—an ocean-going vessel for minimal investment.

Our 1976 Vega was our ‘learner’ boat and it was a great choice because of its great sailing qualities. If was also an affordable size with 5 quarts in a gallon functionality. Omissions in the review: The table had ‘S’ shaped legs, allowing it to be swiveled easily both in the cabin and cockpit, yet was sturdy unlike pedestal-hung contraptions. A typically Swedish clever design. No anchor locker, which was a pain. Engine access was given both through the cockpit sole and with the companion way ladder aside, better than almost any boat I’ve been aboard. And it definitely is a boat you can take to sea. It took us rookies all around the Southern California coast and 4 of the Channel Islands as a family of three, in comfort and safety. And along with John Neal’s many observations about the boat, don’t miss reading Log of the Mahina. We had a chance to show John our Vega when he was back from the Pacific and then we met out in the Pacific Islands 33 years later. He is quite the role model.