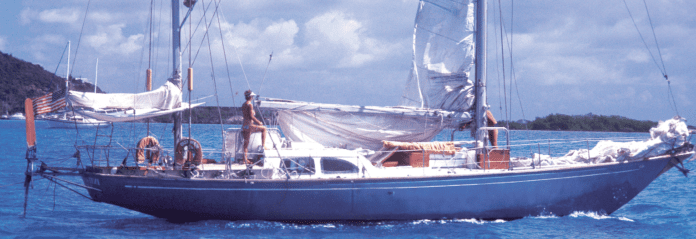

Years ago, one of my first assignments as a sailing editor was to join the famous sailor and yacht designer Steve Dashew and his wife Linda aboard Beowulf, a 78-foot cruising boat that marked the culmination of their revolutionary quest for the perfect passagemaker. The boat was on a mooring in Newport, RI one of several stops on a publicity tour for Dashew’s design ideas, which were setting in motion today’s trend toward bigger, faster cruisers.

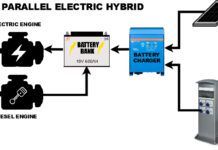

Boiled down, the idea is simple—with experience and conservative seamanship, two people can sail a very big (60-plus foot), very fast boat around the world, permitting them to spend less time exposed to the dangers at sea, and more time comfortably anchored in exotic harbors. The success of this approach relies on hydraulic pumps and electric motors carrying out the work that sailors used to do—from steering to furling sails—and it depends on near flawless seamanship.

This idea was tested in the hands of experienced sailors aboard Dashew’s Deerfoot boats—a line of Dashew

designs introduced in the 1990s ranging from 58 to 72 feet that recorded some very quick passages for their day. Speeds in the teens were frequent; 250-mile days were commonplace. Beowulf needed just 10 days to cover the passage to the Marquesas that took us a month aboard our gaff-rigged ketch Tosca—although I wouldn’t trade a day of that experience for anything. (Speed barely factors into my own notion of a perfect passage.)

On a website now dedicated to promoting a line of power cruisers, you’ll find Dashew’s account of his search for cruising perfection. The article covers his early years as a multihull and small-boat racer through the decades leading up to Beowulf’s exciting launch and early trans-Pacific passages (www.setsail.com/steering-clear-of-trouble-our-search-for-cruising-perfection/).

“What we loved most about Beowulf was how she allowed the two of us to cross oceans on our own. It did take care and prudence, a certain level of physical and mental fitness was required, and we remained aware at all times that Beowulf was ultimately in charge. We had to work together as a team, there was little room for error.”

In the nearly three decades since Beowulf set off on her maiden offshore voyage in 1995, marketing hype has corrupted essential parts of Dashew’s original mission. The emphasis on experience, seamanship, and avoiding risk—lessons that Dashew frequently emphasized, and addressed in depth in a series of books, like Practical Seamanship (www.setsail.com/PracticalSeamanship.pdf)—have been replaced by glowing descriptions of cabin comforts, with barely a nod toward the required sailing experience, and without any mention of the very real

dangers involved.

Even today, the maker of the 66-foot luxury boat involved in tragic fatal accident described in this issue, still advertises boldly in capital letters that “This yacht will be able to guarantee long distances, even with a reduced crew of two people.”

I think Dashew would be quick to state that the sea would never offer such a guarantee to just anyone, no matter how fast or big the boat.