The 1666 London Fire. The 1871 Chicago Fire. The 1906 San Francisco Fire. Common factors shared by all of these disasters were inadequate spacing between buildings, lack of fire stops, and narrow roads. Flames spread from building to building and leapt across roads with little delay. Access for firefighters was terrible. In each case, a manageable fire started in one structure, but soon spread and there was no stopping it once multiple units were involved. As a result, fire codes changed, introducing requirements for spacing, limitations on the use of combustible materials, street and alley widths, and fire stops between structures, but this logic is still foreign to many boatyards.

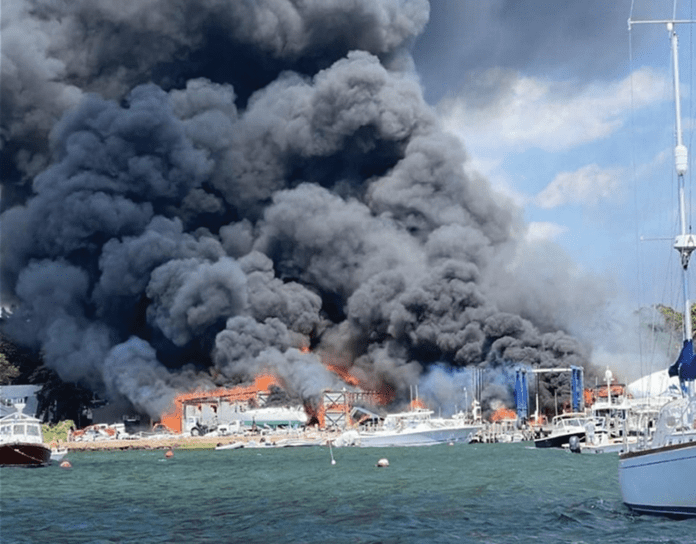

At the Mattapoisett Boatyard, on August 19, 2022, an explosion and fire broke out in a boat repair building. Investigators concluded it was caused by the spark ignition of gasoline vapors in a repair building. From there the fire spread to boats that were placed tightly up against the building, and to rows of boats placed just a foot or two apart. Stands collapsed, boats piled together, and a fire storm ensued, destroying all of the structures and most of the boats. More than 100 firefighters, dozens of trucks and three fire boats responded, but little survived.

Barely three months after the Mattapoisett Fire, a similarly devastating fire raged through Seaport Marine in Mystic, CT. Both fires follow a smaller, but destructive fire at a boatyard in Wickford, RI.

According to fire investigators at Mattapoisett, a spark ignited gasoline vapors causing an explosion and fire that seriously injured a worker. Winds up to 25 mph spread the fire to nearby buildings, vehicles, and boats. Three firefighters also suffered injuries related to smoke inhalation and heat exhaustion. According to fire officials, gasoline was linked to more than 900 fires in Massachusetts over the past decade, highlighting the dangers when dealing with flammables.

“Many of us use gasoline in our daily lives, but we can’t lose sight of the fire and explosion hazard associated with it,” Massachusetts State Fire Marshal Peter Ostroskey said. “Gasoline vapors can travel a great distance to an ignition point, especially indoors.”

The fire reached six alarms, drawing mutual aid from across southeastern Massachusetts and additional task forces through the Statewide Fire Mobilization Plan. In total, more than 100 firefighters battled the fire with 19 engines, 12 tankers, three fireboats, and two ladder trucks before it was knocked down around 6 p.m.

FIRE CODES

In general, the IFC (International Fire Code) and NFPA 30 (National Fire Prevention Association) require a minimum of 1/3 the tank diameter (4 feet for a 12-foot diameter tank) for combustible liquids, such as diesel fuel (NFPA 30 table 22.4.2.1), and the tank must be made of steel or other non-combustible material. Tank support structures must have a fire rating of at least 2 hours (NFPA 30 22.5.2.4)—a standard that most common boat stands do not meet. When we place combustible fiberglass yachts just a few feet apart, there is no access for fighting the fire, flames will jump, and soon the stands will fail, resulting in a burning pile of fiberglass boats laying on each other.

OWNER ACTIONS

Along with a visual survey of combustible storage and use patterns at the yard, take precautions on your own boat. There should be no unattended boat heaters. All it takes is something combustible to fall on a heater for fire to start. Do not leave electrical cords plugged-in when your boat is unattended. Clean-up combustible rags and trash every night (oil and solvent soaked rags can spontaneously combust—I have witnessed this multiple times in my work). Tightly close all solvent and paint containers. Respect gasoline; fueling a boat is not the same as fueling a car. In addition to safeguards built into today’s cars, gas stations have several fireproofing protections—passive grounding through the conductive hose, a non-sparking nozzle, vapor recovery through the nozzle, remote flash-protected tank vents, and breakaway hoses that seal.

There should be no one smoking in the yard. Any dedicated smoking areas should be far away from the boats and work areas. There should be a dedicated fire watch for any hot work that generates sparks (welding, use of torch, etc.).

When storing your boat, insist that the yard allow adequate spacing from other boats—6 feet is a good minimum—more is better. If it is a yacht club, ask yourself if cramming in a few more boats is worth the risk. Can you or contractors safely and easily access the topsides for cleaning and painting?

Storm damage is also more contagious when boats are too close together. Closely spaced boats fall like dominoes. Masts can clash. We think 6 feet is a good minimum, and the yard should explain why they feel less is safe.

An automated fire suppression system won’t protect your boat from a devastating boatyard fire ignited on another boat, or nearby work areas, but it can prevent one from starting on your own boat. In 2020, we reviewed several popular —and expensive—systems designed to activate automatically once a certain temperature is reached (see “New Fire Prevention Tools, PS April 2020).

The first line of defense against fire is meticulous installation following ABYC guidelines. Next is maintenance. Corroded and faulty bilge pump wiring is probably the most common cause of fires in unattended boats. Or perhaps it’s an engine or galley fire. If you are leaving your boat for a long period, you should carefully inspect these high risk areas and take any preventative measures to reduce the risk of fire. Removing moving all flammable materials is an obvious first step.

The systems we looked at had remote tanks of fire suppression material with tubes that could be located in these high-risk areas. These systems are not fool-proof. They need to be inspected and replaced at designated intervals. They also need to be sized appropriately. For more on this topic, see the original report April 2020, and search “fire prevention” on the Practical Sailor website.