On August 18, a sudden, violent storm ripped through the island of Corsica, packing winds up to 140 mph and tossing once safely moored boats ashore like toys. Live YouTube videos show sailors trying desperately to prevent their boat from getting dragged ashore as they collide with others.

But what exactly can you do, if you get caught off guard by a violent squall that puts your boat in danger and gives you very little time to react? One of the biggest dangers is other boats dragging down on yours. Do you head for open water? Do you try to ride it out?

There is no single right answer. How good is your ground tackle? What’s the bottom like? Can you set a second anchor? What risk do other boats present? Is the anchorage shallow enough that breaking surf might be a risk?

If you opt to leave, can you do this safely before conditions become too severe? Is it night or is visibility dropping? Is the harbor too crowded to navigate in the anticipated conditions? Can you get everything ready for sea and weigh anchor in the time available? Does your boat have the required power, and do you have experience maneuvering in strong squall conditions? All of these questions require answers before you can chose a course of action.

DECIDING TO STAY

Will shallow water result in breakers? Breaking waves are typically brought by longer-lasting storms, not squalls. It takes hours for swells to build. The only prevention is to monitor both the forecast and the sea conditions. Tides can also have play a role.

If onshore wind any stronger than a brisk breeze is forecast, you should probably consider alternatives. Breaking waves are also a risk without wind. A distant storm can generate a swell that turns your anchorage into a surf break. Using one of the many weather products that can predict these events is essential to avoiding these situations (see “A New Era in Weather Forecasting,” PS October 2021). When anchored in an exposed roadstead, you should have an escape route planned out, one that you can navigate in bad visibility. Plotted GPS waypoints are helpful.

Holding ground. An anchor will never be better than the bottom it is attached to. If there is hardpan under the sand, the anchor won’t dig deeper and will drag when the wind gets strong. Weeds will hold only until the roots give way. Rock is fine until the wind shifts and you unhook (See “Anchoring in Bad Bottoms,” PS October 2022).

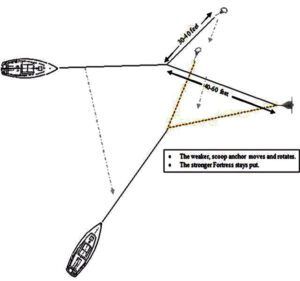

A second anchor. Holding can be improved, particularly in soft mud, through the use of a second anchor in an asymmetrical V-configuration (see “Tandem Anchoring,” PS August 2016 and “Doubling Up; Full Sized Tandem Anchoring,” PS September 2016), but there are down sides. The rig can be difficult to weigh in a hurry if the rodes twist, but they shouldn’t twist if you rig it the way we describe in the two reports.

A V-configuration also presents a 30- to 50-foot wide spread that increases the risk that other dragging boats will get tangled with yours.

We don’t recommend V-anchors for crowded harbors for these reasons. On the other hand, if there are no other boats ahead to worry about, it is one of our favorite soft bottom strategies, and through practice, we have learned how to quickly lay out that second anchor.

SECOND ANCHOR

Cruising boats should always have a second anchor available. A kedge should be on-deck or in the very top of a cockpit locker—not buried somewhere on board. Deploying a kedge can help you escape a dragging boat as well as prevent your own boat from dragging.

If you don’t have an engine, or it lacks enough power to be of any help, wait until your boat swings as far as possible away from the path of the dragger. Lower the anchor from the beam (not bow), and then release some scope on the main anchor. As the scope on this kedge becomes about 3:1, set lightly and take it to the bow to tighten up. This will draw the boat to one side, hopefully enough for the dragging boat to pass. If by some horrible luck he fouled your bower anchor, you can release it on a buoy and use the kedge as your new primary.

DECIDING TO GO

During summer, sailors frequently find themselves on a potential lee shore when thunder starts grumbling or tall clouds appear on the horizon. It’s up to you to do the math, and decide whether the risk of exposure to breaking waves is too great, the anchorage too crowded, or the holding ground too sketchy to stay. A few times, we’ve pulled up anchor and moved, and later learned that boats ended up aground or banging into each other.

POWER ESTIMATES

Do you have the power? There are many variables (windage, sea state, hull shape), but some estimates are possible. The wind-only load (based on PS anchoring studies) is roughly 1/5 the figures used by the ABYC to estimate design loads for deck hardware at fixed windspeed (see “The Load on Your Rode,” PS September 2004).

Waves will add 20-35 percent, depending on the amount of exposure and the depth of the water; shallow harbors are bad in onshore conditions, and breaking conditions are deadly. A typical engine produces about 25 pounds of thrust per horsepower, although this can be greatly reduced by pitching. Outboards are 10-30 percent less powerful, depending on the prop and the gearing.

A modern 35-foot boat, in winds of 60 knots, would need at least 540 pounds of thrust (2,700 pounds/5) or about 21 hp just to just hold station, assuming it has a powerful, three-bladed prop. This produces no forward motion and does not account for waves. If the boat turns sideways it will be pushed downwind. To make sufficient headway, you’ll need at least 70 percent more power, or about 35 hp. These are very rough estimates, and will vary greatly by the boat’s weight, hull shape, and amount of wetted surface.

There are more challenges. The boat will need to be held steady over the anchor as you recover it. With a twin-engine multihull this is not too difficult; instead of steering with the wheel, you play the throttles, keeping the wind dead ahead.

An outboard-powered boat can steer with the engine if it is accessible. But a single screw monohull is nearly impossible to hold steady into the wind and waves while making no way. You risk getting sideways and taking off at a gallop. You’ll need enough extra power to regain control of the boat. The wind may also increase while you are in the middle of all this.

The only real way to know your boat’s limits is through trial and error. Next time you find yourself in a squall with room to experiment, practice going slowly, holding station, and motoring at different angles. Stop, let the bow fall off, and see how hard it is to regain control.

How much does the wind slow you? How much throttle does a given windspeed require for good maneuvering, remembering that the difference between 1/2 throttle and full throttle is much less than 50 percent more thrust.

ANTICIPATING POOR VISIBILITY

At night, it will be dark as the inside of a cow, with no moon or stars. Even at mid-day, visibility can drop to 20 feet or less, and that hardly matters, because with 70 knots winds and horizontal rain, you can’t look into it anyway. Sure, you can wear goggles or a swim mask, but you still won’t be able to see much beyond the bow of the boat.

CHESAPEAKE SQUALL

Just this past summer I experienced the most extreme white-out squall in my 40-years of sailing. I was single-handing an F-24 trimaran, which was anchored off the beach in four feet of water. I was lounging below and didn’t see the saw the squall until I poked my head up because something didn’t feel quite right. Not an opening puff, just something not right.

Less than a mile away I saw a white wall, with zero visibility under the storm. I quickly battened everything down, weighed anchor, and pulled on a Gore-tex paddling jacket, knowing the rest of me was going to get soaked. The last thing I did was try to memorize the range and relative bearing of every boat, swim platform, and boat within 1/2–mile. I knew that when the storm reached, they disappear from view. I had only enough time to motor a few hundred yards into a clear area before the rain hit.

Within seconds I could just barely make out the pulpit, and looking astern, I could see just about the same distance—20 feet at most. I had swim goggles, but there was no point in facing forward. Instead, I mostly I faced aft, steering with the outboard, keeping the boat oriented into the wind and intentionally making no way.

I’ve also weighed anchor and left an anchorage at night, but only when I was sure I could navigate the passage to open water. I’ve never weighed anchor with the wind above 30 knots. In those conditions, I rigged a second anchor and sat it out. During one such storm, the hail was big enough to break car windows and fill the cockpit with iceballs two inches deep, but the anchors held. It took nearly an hour to free my Fortress anchor from the bottom.

CONCLUSION

If there are thunderstorms in the forecast, or if it is even just the sort of unstable weather that can produce them, consider staying onboard or very near the boat. Anchor like you mean to ride out whatever comes. Anchor in water deep enough that the waves can’t get steep. Use long scope, no matter how the naysayers feel. Use a long snubber to buffer the jolts, and do the same even on a mooring. Yaw-prevention measures should be in place.

Few of the boats in the Corsica event had any option except to hope that their mooring or anchor held, and that no boat would drag down on them. Their only option was to focus on keeping their crew safe. You can’t fully plan for such incidents, but it is good to think about them each time we set the anchor.

We’ve explored ways to set a second anchor in multiple other reports in the past. You can improve holding, particularly in soft mud, through the use of a second anchor.

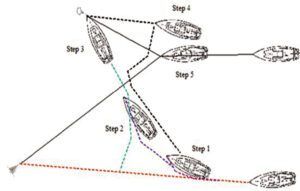

2. Motor toward new anchor spot.

3. Drop secondary anchor.

4. Set secondary anchor using engine.

5. Attach 2nd rode to primary rode.

6. Back down on primary rode.

1. If you have enough power to maneuver and are worried about a conventional twin-anchor rig getting tangled, an asymmetrical rig is an option. There are couple proven ways to attach the secondary rode to the primary rode (see “Tandem Anchoring,” PS August 2016 and “Doubling Up; Full Sized Tandem Anchoring,” PS September 2016)

2. If one anchor in an asymmentrical V-tandem rig drags, it is unlikely to tangle with the other.

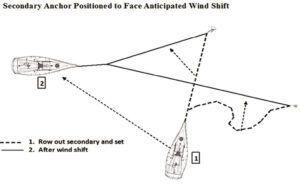

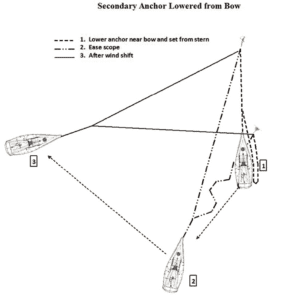

3. If you have enough time in advance of the foul weather, you can row or motor the anchor out in the direction of the anticipated wind shift.

2. Ease scope.

3. After wind shift.

4. In a V-tandem the secondary anchor should provide improved holding and in position so that both anchors will carry the load of the wind shift brought by the storm.

What about a discussion or investigation on anchoring from the stern in major storms? I have been creating a Jorden Series Drogue for my ketch for at sea storm survival. The drogue attaches via a very stout rope bridle to two points on the stern and has a very good track record going stern to in hurricane force winds. Its called the “the sailor’s airbag”.

Dan Jordan the aeronautical engineer who developed the Jordan Series Drogue also investigated anchoring from the stern in hurricane and high wind type events. There is a very good article on it at this site. https://www.jordanseriesdrogue.com/D_14.htm

I have not tried it yet, but will be experimenting with my Jorden Drogue attachments points for stern anchoring. The concept is to use a dedicated “boat length” long rope drogue bridle attached at the stern. This bridle and line becomes a long “anchor snubber”. Shackle this long snubber to the anchor chain or anchor rope at the bow and then let out another 2 plus boat lengths of chain and the boat will swing 180 degrees and be stern to the wind. This lets you use the traditional bow windlass and primary anchor/s for both the bow and stern. With this method there is a loop of chain hanging under the boat that might get caught on the bottom in shallow anchorages so addition rigging might be needed to hold the chain under the boat up off the bottom. In very light winds this “long snubber” method is also used to hold the boat at any required angle to the sun to make better use of solar panels.

Even my full keel ketch with the mizzen sail up swings on anchor in serious winds and I could see how chaff and stress would be an issue in a big storm. Anchoring from the stern might calm it right down.

Our suggestion is to try it in more benign conditions and see what you learn. We did investigate this and concluded that although stern anchoring damps yawing, there are many downsides.

https://www.practical-sailor.com/sails-rigging-deckgear/the-science-of-stern-anchoring

Bridle lengths for drogues and JSDs are typically 2-3x the beam. Greater lengths lead to single leg loading and rapid fatigue of the line (ropes do not like load-slack-load cycling). Long legs can also lead to tangles. Additionally, a nylon bridle is NOT recommended for JSDs. It is too chafe prone and the shock absorption does not help. The JSD bridle should be either polyester DB, or preferably, Dyneema. Later experence, with Don Jordan’s aproval, suggests that polyester and Dyneema are also better rode materials, since they are more durable, reduce recoil, and because rode stretch is not actually desirable. Unlike ground anchors, the JSD moves through the water, absorbing shock through its movement. The tail weight, for example, has proven very important and should not be reduced.

For anchoring with all-chain rode you will want a nylon bridle.