We wouldn’t describe ourselves as huge fans of composting/desiccation heads (see “Dissecting the Desiccating Head,” PS July 2021). We’re not encouraging people to rip out what they have or even to go that way with replacements; a properly installed and maintained holding tank system works very well and fits the needs of most sailors. We see composting/desiccating heads as a solution when pump out facilities are sparse or non-existent as in some lakes and rivers, to save weight and space in small boats, for day sailing when head use is minimal, and for severe winter situations when freezing becomes a problem.

Some people are offended by the very idea of composting heads, or can’t see themselves using such a system. As a result, any disposal option for composted waste offends them. Taste, however, does not determine the “rightness” of either system, and neither is perfect. What matters is that each disposal method is carried out safely without an undue risk to the user or the communities impacted.

The waste from composting toilets in continuous use is not true compost. It is partially digested, desiccated solid waste. This designation is the source of some of most objections to common disposal methods, which is to throw the desiccated waste into the nearest dumpster. In the minds of many, solid waste belongs only at a solid waste treatment facility. But we’ve long accepted some forms of waste disposal that don’t meet this standard. Dumpsters legally accept diapers, bathroom waste, household infectious waste and household sharps (needles), as well as dog and cat waste. There is no expectation or requirement to restrict dumpster waste to stuff you can safely swim in.

It is worth noting that waste removed at a pump-out station also comes with some health risks. Sewers legally accept human infectious waste and even hazardous waste within certain industrial permits, a nasty mix that sewer and treatment plant workers are in contact with every day. Workers who pump out portable toilets deal with this through a combination of personal protection equipment, hand washing, and vaccines.

When you pump out your holding tank into a municipal systems, that’s not the end of it. When it rains, municipal systems overflow into local waters, and even separate sewer lift stations can overflow due to mechanical and power problems. The difference between your composting head and municipal systems is that everything related to municipal sewage is defined and regulated. Since the rules for disposing composted waste are still nebulous, it is up to us, the community of users, to develop safe and responsible best practices for composting toilets.

ISOLATED PROBLEMS

After interviewing fellow cruisers and researching the topic, we found remarkably few reports of controversy over disposal of composted waste. We also were unable to find many rules that had been introduced to help manage any conflicts linked to disposal of composted waste. Here are examples of the isolated problems we found.

ANNAPOLIS HARBOR

Located in our local cruising area, we’ve spoken with the harbor master on several occasions. The root of the problem is a few individuals who dump their waste in the typical coffee cup waste bins located alongside the park benches at the dinghy dock, instead of walking their waste a mere 50 yards to the city dock dumpster serving the municipal marina. The cans fill up, overflow, and townspeople, not unreasonably, complain. The result is a city requirement that all visiting boats use the pump-out service at least once every two weeks, or they will be asked to leave.

CANYONLANDS

Desert campers placed too many WAG bags in small bins at Canyonlands National Park, which ruptured when the trash compactor squeezed them. This really should not have been a surprise, because just weeks earlier the Park Service issued a new mandate requiring all campers to carry out their waste. I’m sure the cans at the trail head seemed to be the logical receptacle, placed there for that reason. The Park Service immediately labeled the cans “No WAG Bags” instead of recognizing they triggered the problem. Note that WAG bags contain liquid waste as well as solids, use less absorbent, and are sealed immediately after each use, which prevents the natural desiccating process. The waste in a wag-bag is very different from composting/desiccating toilet waste.

CANAL AND RIVER TRUST, UK

The canal system is home to many liveaboards, the pump out system (Elsan) is relatively expensive ($20-$30 per use versus $5-$10 in the US), and is not always convenient to boats that don’t move constantly. Combine that with small waste bins, the contents of which are manually sorted for recycling (no separate recycling containers), and it has become a practical problem. The Canal Trust, a non-profit which manages the canal and trail system issued a position statement March 2021 requesting that solid waste not go in their bins and that boats convert to holding tank systems. Diapers are still permitted.

BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES

By adhering to best management practices for composting heads we can prevent this sort of blowback. Based on our research, the following is what we’d consider safe, reasonable practices.

OPERATION

Proper head operation is vital not only to eliminate odor and maintain user satisfaction, but also to ensure that waste products are stable and non-objectionable. Urine must be separated from the solids through careful use of the separating seat. Mixing urine with solids increases odors and results in a sloppy product.

An anti-odor treatment, such as vinegar, citric acid, or Nilodor will keep the urine inoffensive when disposed in a rest room (see “Additives Fight Urine Odor,” and “Wood Ash Absorbs Odor Best,” PS July 2021). Sufficient effective absorbent and adequate ventilation results in a desiccated product with minimal odor and reduced spill potential. Do not wait until the head is overfull, since a little extra absorbent should be added prior to disposal. Adjust these recommendations to suit your specific equipment and situation.

DISPOSAL

Responsible management and discreet disposal are the goal.

Urine Container. Disposal in a public restroom is the preferred option; treated urine is nearly odor free. Disposal in the woods, well away from the water, is acceptable in remote areas.

Solids. Adding our solid waste to a composting system is the best option for solids when practical. I’ve done this with land-based systems, but not on the boat. Because our test boat is primarily day sailed, the head is used only a few times each year. If I cruised locally and lived near the boat, we would add our boat waste to our compost pile. Mixing with partially composted yard waste for daily ground cover is fine, but you want to control run-off by avoiding use near a drain or gutter. Thin layers of cover above ground are better than an in-ground pit.

Time. One year is recommended time required for passive composting. This is about the same time period as passive composting for mixed yard waste.

COMPOSTABLE BAGS

Biodegradable is not the same as compostable. Most biodegradable bags require UV to break down, so once you bury them they won’t decompose. Compostable bags, on the other hand, should break down, but they will slow the composting process by blocking oxygen transfer. Testing says most compostable bags will not fully degrade within a year in some piles. Compostable bags tend to be a little thin, so you will want to contain them in something during transport. You should not use them for bucket liners for extended periods for obvious reasons.

BAGS FOR DISPOSAL AS TRASH

Bags bound for the dumpster should be double-bagged and well sealed. Commercial WAG bags are typically 1-2 mil inner and 2-3 mil outer, with a generous allowance for tie-off of the inner bag (electrical cables ties work very well), a zip-lock closure on the outer bag, and an odor barrier or absorbent gel (an aluminized bag is one approach).

There should be no chance of rupture transporting or in the dumpster before compacting. If you don’t want to splurge for a wag bag, or the industrial 1 mil heavy-duty kitchen bag inner bag and 2-3 mil heavy-duty outer waste bag with secure closures is acceptable. For longer trips without a chance for disposal, double-layer bags, like the “double doodie” bag (see “Controlling Porta Potty Odor, PS September 2018).

SOLID WASTE DISPOSAL

Use only dumpsters handled by machine, not small waste cans or wheeled bins. These provide maximum dilution with other waste and minimum handling. In general, cruisers should dispose of their trash in large bins rather than overfill smaller trash cans.

CONCLUSION

Outside the 3-mile limit, overboard disposal of both liquid and solid waste is legal and responsible. Nature will take care of it. The best management practices described above apply to inland and coastal waters. As onboard composting becomes more common, failing to follow these common sense steps will wear out the welcome that cruisers before have carefully cultivated.

1. The small bag from Cleanwaste fits right inside our portable, taking the mess out of solid waste disposal. We also tested a variety of anti-odor treatments for porta-potties (see “Controlling Porta Potty Odor,” PS September 2018).

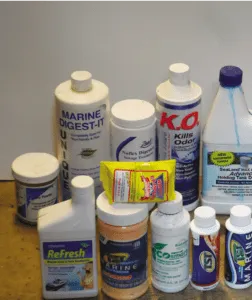

2. PS has tested a wide range of odor-fighting, cleaning, and maintenance products for boat and RV heads and holding tanks (see “Stopping Holding Tank Odors,” Part II, PS December 2012)

3. Even mild acids like vinegar, when overused, can harm joker valves on marine toilets (see “Clean Potty Overkill,” PS December 2019).

Thanks for the information. I have just purchased a boat with a composting head. I knew nothing about them. Now I know a little more.