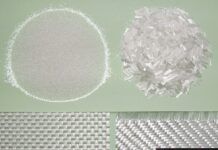

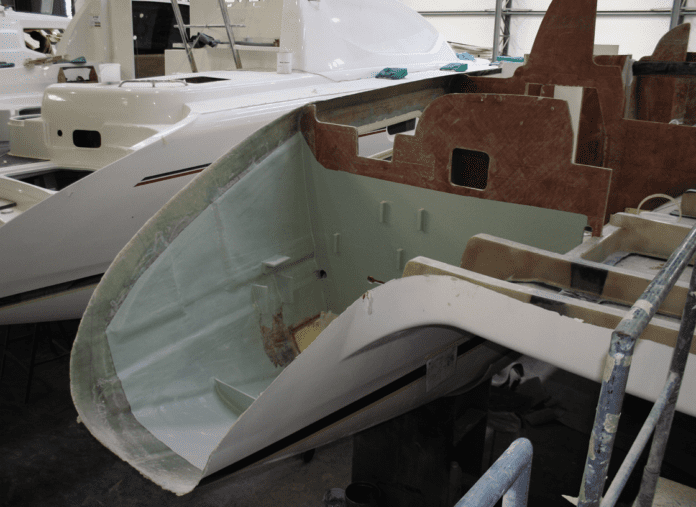

In a stick-built boat, a shipwright builds piece-by-piece the interior furnishing—lockers, berths, settees, etc. The interior structures on contemporary boats, by comparison, are often pre-molded into one or more large “pans,” fiberglass liners, usually finished with gelcoat on the facing surface, that are bonded into place.

The use of a pan accelerates construction and reduces cost, but it also complicates modifications, and can render invisible or inaccessible parts of the bilge. Even on a boat touting a “non-structural” liner, cutting willy-nilly through the liner to make room for ducts and stereo speakers runs the risk of weakening the boat’s original stiffness. Doing so can begin a cascade of failures that can become expensive if ignored.

Like pan-liner boats, stick-built boats are susceptible to weathering, age, and the persistent bending and flexing that can weaken structural bonds.

It’s easy to forget that behind the boat’s fine joinery are the resins and glues of another era, and that the hull, keel, rudder, and rig depend on these adhesives retaining their original properties. How long can these glues last? Could any suffer the fate of the adhesive sealant 3M 4000 UV, which reverted to goo at just the five-year mark during our testing? (See PS Seeking Reports of 3M 4000 UV Failure, PS April 2022).

We’ve not heard of any sudden failures of the time-tested structural adhesives used in hull-deck joints today, but there have been plenty of bedding compounds and elastometric sealants on older boats that dried out, cracked or sheered after years of flexing.

More often, the question is not which resin or glue the builder relied on—but how the builder used them. Is the adhesive a temporary measure until fiberglass tape or through-bolts are used to reinforce a rugged joint? Or is the glue the sole bonding agent?

More frequently, it is the latter case—with the miraculous methyl methacrylate (Plexus) alone keeping parts of our boat together. Overall, the record of methyl methacrylate adhesives (MMA), two-part epoxies, and marine-grade sealants is impressive. The problems arise when we choose the wrong glue, or flub the application. I’m not sure how much re-sealing I have ahead. The real test with Opal, my 1970 Yankee 30, will be in a heavy seaway, when the dribbles and drips at the joints let me know that the boat is really working—perhaps a little more than it should.

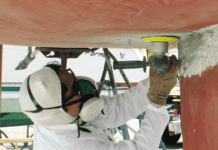

And this brings me to my final point —and Dad-joke setup. Not every deck leak is due to a simple glue-line failure that can be plugged. On an old boat, the leaky port, mast step, or hatch often needs more than just another dollop of putty. The core and laminate around it might require stiffening with additional laminate, stringers, or new core material. The aim is to prevent the area around the seam from flexing too much, which prevents a good seal and can lead to more serious repairs.

As Dad liked to say, “A stick in time saves nine.” (You were warned.)