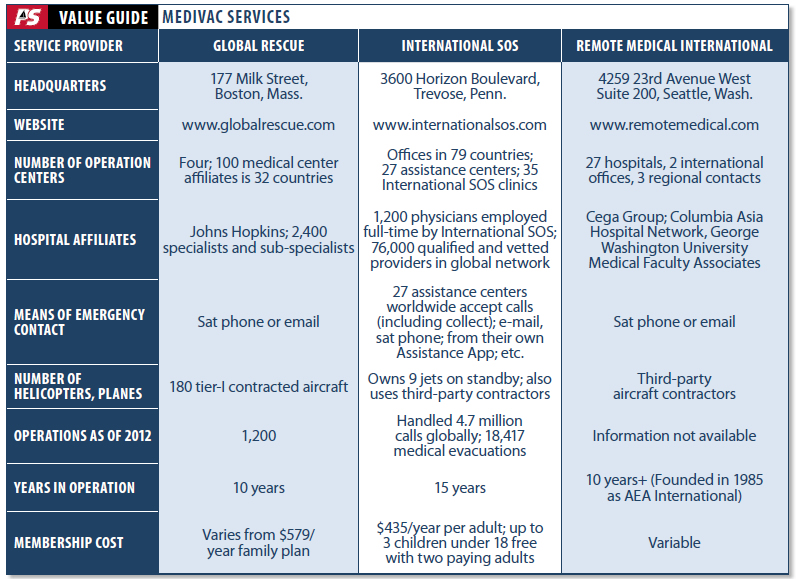

Editors note: Although we recognize that only a handful of our readers ever venture to remote regions of the planet, we know that many dream of doing so. The advent of affordable satellite communications has introduced an array of medivac and telemedical services for remote travelers that were impractical only a few years ago. We decided to find out more about these services. Because a balanced test seemed impossible, we submitted detailed questionnaires to three principal providers, and tabulated relevant information that could be used for comparison. As each company spokesperson indicates, which service-if any-suits your proposed adventure will depend on a number of individual factors that you will need to discuss with prospective providers.

Imagine youre sailing off the coast of Patagonia, Africa, or Indonesia, when a crew member complains of abdominal pain so severe it could be a sign of appendicitis.

Knowing appendicitis can be fatal if left untreated, the captain uses his satellite phone to reach the pre-contracted service in the United States that provides medical advice, air-ambulance service, and remote evacuation, if needed.

Since the boat is several hundred miles from land, a helicopter wont be coming to the rescue. Besides, hoisting a seriously ill or injured person from a sailboat is dangerous business for all involved. The company operations center says it can arrange a medical flight once the patient is ashore. Meanwhile, the ailing sailor must be stabilized while the boat heads toward an acceptable harbor. And even then, the nearest surgical hospital where Western-style medicine is practiced will likely require a long, bumpy road trip.

As this emergency unfolds, the skipper must decide on a course of action that will, in many respects, be predicated by decisions made weeks or months before setting out on the expedition- when captain and crew met with the contracted companys staff of emergency medicine, communication, and survival experts. The meetings were essential because while evacuation by air might be part of the service contract, implementing one isn’t always possible.

Such pre-planning can include the assembling of comprehensive medical kits capable of addressing a wide range of sicknesses and injuries, from broken bones and lacerations to dental emergencies and malaria. The most useful kits are stocked with prescription drugs matched to the medical conditions of those aboard. These drugs are commonly used to treat asthma, high blood pressure, hypertension, heart disease, or diabetes.

Some remote evacuation companies employ ex-military personnel-often Navy SEALs and Army Rangers-to oversee assembly of these medical kits, provide crew members with emergency medical training, and teach them how to operate the satellite phone and other communications equipment aboard. After all, there may be circumstances like the one described in which the company cannot deploy rescue personnel to the location due to distance, weather, location, or war, so the thoroughly equipped and trained sailor stands a better chance of survival. Thats where the importance of telemedicine enters the picture.

Although the technology behind telemedicine is rapidly advancing, its still not a matter of pushing a button to activate a two-way video transmission in real time between the sailboat and a team of doctors. Its not Star Trek-at least not yet.

Practical Sailor recently took a look at a handful of global companies that offer telemedical and medical evacuation services for those sailing the less-developed parts of the world. The first step to deciding if membership to a medivac service is right for you is to assess your needs, cruising area, and ability to address medical emergencies or injuries on your own.

We strongly recommend people who are going to sea get some kind of satellite phone, said Dan Richards, founder and chief executive officer at Global Rescue, a U.S.-based company that provides medical advisory services, security, and emergency flights almost anywhere in the world.

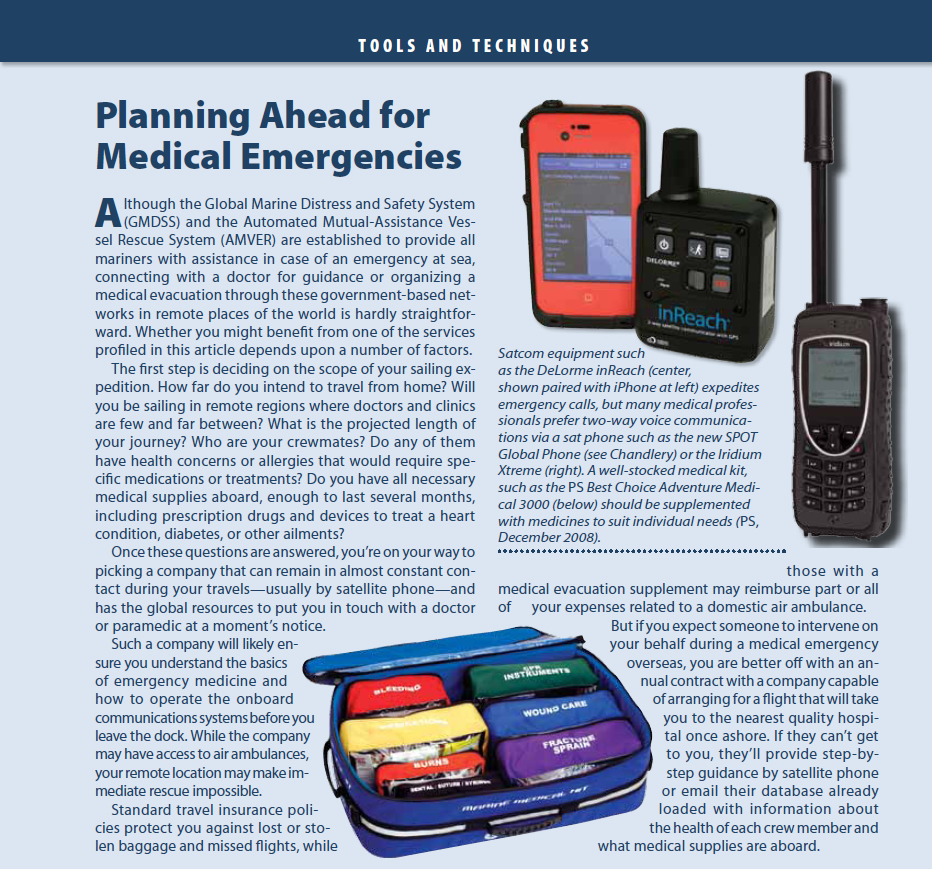

According to Richards, maritime radio communications can pose a challenge when trying to diagnose and treat illnesses, and satellite uplinks afford the most reliable channel. He was reluctant to endorse GPS messenger devices such as the popular SPOT Personal Messenger (PS, September 2008), which can send out alerts to would-be rescuers. Although such devices-called SENDs (satellite emergency notification devices)-relay the senders latitude and longitude to those on the monitoring end, theres no two-way communication as there is with a satellite phone such as the Iridium Extreme and SPOT Global Phone.

Ninety-nine percent of the SPOT alerts we receive are false, Richards said.

Because satellite phones and related transmission charges can be expensive, Richards said some travellers to remote regions are relying on newly developed smart-phone applications and devices such as the DeLorme inReach (PS, March 2013), which links a smart phone with a satellite via Bluetooth.

But you are limited in the number of characters you can text, and if you need immediate medical assistance, texting doesn’t work very well, he said. With a satellite phone, we can put you on speaker (phone).

Texting typically leaves the device user with no free hand to address an injury, help sail, or perform other duties.

Global Rescue, a major player in the remote rescue industry, has 24-7 operation centers in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Thailand, and Pakistan. The company also maintains a partnership with Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Md., where doctors are on standby. Members who subscribe to Global Rescue are provided a phone number and email address to use in an emergency.

When the first phone call comes in, you could be speaking with a paramedic. We get lots of calls per year that involve cuts or bleeding or people experiencing cardiac arrest, Richards said. Its no different on a sailboat. We can walk you through it. Some things you can do on the phone with help from medical professionals. We provide advisory services more often than we evacuate people. Our medical team works with you. If youre in the middle of the Atlantic or the South Pacific, thousands of miles from land, your options are limited. We can walk you through and mobilize resources to move in your direction.

Those resources can include arranging helicopter or plane flights piloted by subcontractors worldwide; setting up ground transportation; staffing a field clinic with paramedics; and identifying the most appropriate hospital in the region.

Were the only company in the world that comes to your location. We did 1,200 ops this year, Richards said, adding that over the past 10 years, his company has provided medical, security, and evacuation services at just about every major global disaster. Earthquakes in Haiti, a tsunami in Japan, the Russian invasion of Georgia province, rioting and political instability in Egypt, terror attacks in Mumbai-these all required Global Rescue evacuations.

Every day, we get folks whose events don’t make the paper-animal attacks in Africa, lions and cheetahs, people who end up in an encounter, Richards said. We had a woman gored by a Cape buffalo in Zimbabwe. We got a call from the safari guide after the woman gave them her Global Rescue card or number. We deployed a helicopter for field rescue, to Victoria Falls, where we got her to a clinic. She was evaluated and stabilized, then a fixed-wing aircraft evacuated her to South Africa, where she stayed in a hospital for three weeks to stabilize before going back to Texas where she lived. We saved her life, although she never regained use of her lower extremities.

A few years before that incident, a recreational sailor in the Bahamas got his leg trapped between the vessel and a pier. His lower leg was broken. There was no clinic on the island. We instructed the people with him (via satellite and cell phones) on how to construct a splint. We actually got some pictures of the guys leg. And we got a fixed-wing aircraft to evacuate him to Miami.

The procedures are much the same at Global Rescues competitor, International SOS, a worldwide provider of medical assistance, security, and evacuation services, with offices in 76 countries.

Patrick Deroose, general manager of International SOSs Corporate Assistance Division, said recreational sailors in remote regions might best bone up on emergency medicine procedures and acquire long-range communication equipment.

If you are sailing off the coast of Mozambique, we would have to get you to a port of call that we use, he said. We would determine if the best care is locally or whether you must be evacuated.

International SOS has nine fixed-wing jets that serve as air ambulances. It also partners with an Iraqi company to extract people from war zones. The company makes use of existing aircraft providers but maintains its own planes in New Guinea, Namibia, Singapore, Beijing, and Africa. And other places where you don’t expect to have aircraft. These are dedicated aircraft waiting on the tarmac for something to happen, he said.

Like Remote Medical, the company charges an annual membership fee based on a variety of factors.

For sailors, it all starts with preparation, said International SOS spokesman Michael Burkhart. A lot depends on where the voyage is going. We provide country guides, city guides, make assessments of whats on board, the crews medical conditions, and any existing problems. We try to get a basic understanding of each guest on board and that information goes into our files. Based on that, we make recommendations for what they should have on board for first aid, depending on the length of the voyage. It could be up to a full paramedic bag.

Burkhart said commercial maritime vessels often have a device on board that can monitor a patients vital signs and transmit the information via a digital base station to doctors who can analyze the data.

Tom Milne, relationship manager for corporate logistics and executive services at Seattle-based Remote Medical, a company providing on-site and telecommunicated emergency medical services in far-flung regions of the world, said sailors must prepare for more than evacuation.

According to Milne, sailors must consider the distance their boat will be from the nearest medical help and take every precaution necessary before embarking on their journey.

We operate in remote areas to provide medical support to our clients. These are locations that don’t have direct access to the Western healthcare structure, he said.

Milne said many travellers mistakenly believe all bases will be covered if they purchase travel insurance that includes a medical evacuation plan. People think, if I get this in place, Im taken care of. That is dangerous thinking, he said.

Remote Medical looks at the integrated package, he said, explaining that training, provisioning, and medical and logistics planning are as important as the evacuation plan.

Its not Disney World. Things go wrong, he said. Evacuation can be part of the mix, but medivac is typically complex, can take a long time, and whether or not you have insurance it can be costly.

To illustrate his point, Milne hypothesizes an accident aboard a sailboat in the South Pacific. If you have the proper training, you can identify what might become a bigger issue later on, he said. For example, you need to know how to treat a wound effectively. In tropical areas, it takes only 12 to 24 hours to become a systemic infection that can be fatal.

Milne offered another scenario. If somebody has an allergy or is stung by an insect, its going to require immediate treatment with the right equipment. If you don’t have (an epinephrine) pen on site, your window of opportunity is closed in 20 minutes. So one of the first things we do at Remote Medical is get people to understand the context of their challenge.

Remote Medical staffers routinely discuss these possibilities with cruisers, he said, adding, We want to understand what their trip is about, their existing capabilities, and what their goals are.

Proper provisioning, multiple medical kits, a logistics support package, and a subscription to an associated telemedicine service are key, as is emergency medical training, Milne said.

Remote Medical will fly an instructor to the yachts location before its crew departs. Typically its a medical instructor. We have a family right now doing a three-year boat trip to South America, the Caribbean, and then the Northwest Passage. We are flying an instructor down to meet them in Southern California. We have flown instructors recently to New Zealand and Fiji, he said.

If a medivac is possible, several considerations will impact its speed and effectiveness, including the availability of the appropriate aircraft; the aircrafts point of origination; the capability of its crew to handle a medical transfer; rules governing medical flights; and any existing airspace issues where the political climate is less collaborative.

You might be a slam dunk and have a plane on site in 24 hours. But in remote areas of the South Pacific or Antarctica, a straight shot with a big plane might be seven hours. And then theres the weather. You can experience no-fly weather in Antarctica for more than a week, Milne said.

When Remote Medical receives a call for a medivac, depending on location, it can contact Cega Group, its UK-based business partner.

Cega owns a variety of air ambulances, Milne explained. The company provides medical and security evacuations on a global scale, doing 50 evacs a month and 2,000 repatriations each year. (Repatriation means moving a person who needs medical care but is not in critical condition).

We can access their medivac assets, he said. People need to understand that in the interest of patients, companies look at the worldwide network of medivac providers. Any provider with a dedicated fleet would be a finite asset. Most important is to have the coordination. People should also understand that some patients are not good to fly. Once we understand a clients circumstances, we can set them up to go to a specific medical facility or pharmacy.

Remote Medical also has the option of diverting patients to another partner, the Columbia Asia network of hospitals.

Whether you should subscribe to one of these services depends on a number of factors, not the least of which is how much risk you are willing to take. Those who are coast-hopping in developed nations will likely be served fine by local rescue agencies. And some health insurance policies include evacuation coverage, but youll want to read all the fine print to make sure you know what exactly is covered and what isn’t. Companies providing global security as well as remote medical evacuations tend to distinguish themselves from those simply in the business of providing travel insurance. All advised taking a hard look at blanket travel policy provisions and restrictions.

Look at your travel policy carefully, Milne said. Our service can begin in the middle of the ocean and doesn’t end until they get you home or to a hospital.

Richards was equally emphatic. We can deploy security personnel to you, evacuate you to a safe location, and bring you home, he said.

Even if you decide to subscribe with one of these medical services, it is important to remember that there is no assurance that they can reach you quickly in some of the most remote regions of the world, such as the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Sailors looking to venture farther afield need to plan ahead by training in emergency medicine and learning how to operate the satellite communications aboard their sailboat so that a doctor back on land can tell them how to proceed.