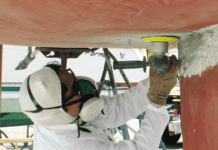

We like premium multi-season paints, particularly for sailors who sail year round. The copper leaches into the water more slowly than single season paints and the costs of hauling, scraping, sanding, and repainting are reduced by half. Yes, the paint costs a little more, and two coats are applied, but there is also less buildup and less to strip years later.

But no paint is perfect, and even the best paints require regular diver cleanings in high fouling waters like San Francisco. Chesapeake Bay boats generally stay clean the first year, but some scrubbing is generally required the second year. See “Bottom Paint Care” and “Cleaning Your Hull,” Practical Sailor, April 2018. (Search “bottom paint” on the PS website for an extensive archive of multiple test reports.)

In northern climates, once the water cools below 45F, growth slows, and soft growth and slime fall away when the temperatures near freezing. But in the spring, fueled by long days and nutrient-rich waters from spring floods, growth takes off like a rocket. The first cleaning is often due when the water is in the 50s, far too cold for swimming without a wet suit or dry suit.

Harbors aren’t always the cleanest places; there are oil leaks, failed septic tanks, and boaters that don’t follow pump-out rules. (See PS “Coexisting with No Discharge,” June 2020.) Electric shock drowning is a serious concern in fresh water (see “Electric Shock at the Dock,” Practical Sailor, August 2019). And then there is the bug factor. Every time we emerge after hull cleaning we are covered from head to food with the critters that live in the soft growth. Wearing a balaclava keeps them out of our ears and hair, but we’re sure they get some places they shouldn’t. We try not to think about it.

Enter the Scrubbis from Davis Instruments ($65). Consisting of a 4- to 10-foot (adjustable) aluminum handle, with a 12-inch dogleg bend and a 4-inch x 15-inch scrubbing head on the end. I was a skeptic and dragged my feet on testing for several years. What good could be accomplished with a handle that long and no leverage? To make things worse, my trimaran has terrible access problems caused by the trampolines connecting the three hulls. As it turns out, it really works!

TESTING

First, we waited until month 26 on West Marine PCA Gold (two coats, sailed every 1-3 weeks year round). A very few barnacles had started growing few months before, but not so many we couldn’t just pop them off with a thumb. Fast sailing was no longer keeping the soft growth completely in check. We’d given it one light wipe down a month before, following PS recommendations for 2-year soft paint maintenance, but the slime was thriving and a few dozen small barnacles had moved in. Just 15 minutes with the squeegee-like standard head Scrubbis got it clean, including the bits where access was blocked by the tramps.

Winter passed, and we gave it another go at month 33. It was late May, the water was warming, growth was starting, and surely the paint was nearly done. Again, the Scrubbis took off the emerging slime and baby barnacles in about 15 minutes. I was impressed and thrilled, because I’d left my dry suit at home and 60F water is overly invigorating for my tastes.

OBSERVATIONS

Unplug the boat and the neighboring boats. You will be reaching into the water with an aluminum pole and we have experienced a tingle before while swimming in a marina. All it takes is a boat with bad wiring. But with your feet on deck or dock, it’s obviously safer than swimming and the only safe option for in-marina use by freshwater sailors. Rubber insulating gloves and dry shoes can add grip and safety. A non-conductive hose over the handle wouldn’t be dumb.

Use the Groovy cleaning head. The stiff bristles on this optional cleaning head ($45) make short work of soft growth, it conforms well to curves, and washes off easily with a hose or just bouncing it on the surface of the water. The standard head is easier on the paint, but if there is significant hull curvature, the contact patch is rather small.

Let the float do the work. Instead of scrubbing hard using the pole, push the brush down first, under the boat, and let the float do the work on the upstroke. We measured the float buoyancy at 6.7 pounds, which seems a good compromise between cleaning effectiveness, maneuverability, and paint preservation. We doubt a swimmer could press any harder. Most of the cleaning is actually accomplished on the up-stroke.

Of course, the buoyancy only works when it is under the curve of the hull, or in the case of the keel, when there is a significant angle between where the handle is held and the vertical surface.

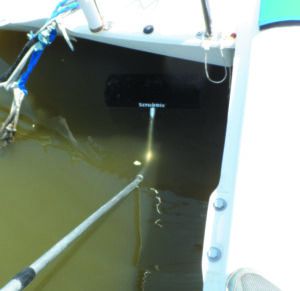

We were able to reach the entire underside of our test trimaran, including both floats and the entire center hull, by using the buoyancy of the float to scrub areas far under the trampolines. There were only two areas that gave us trouble; the waterline and the centerboard case opening. The former can be scrubbed from a dinghy, by reaching down, or using the Scrubbis Waterline Brush (not tested). The centerboard case, and likewise props, through hulls, and speed sensors, will always require occasional hand detailing with a brush, plastic scraper, screw driver to keep them clean and clear of barnacles, but that takes only a few minutes and can be neglected during the cold water season, since barnacles stop growing.

Don’t expect miracles with barnacles. Babies come off with the slime, but once they are established, a plastic scraper is the only solution (see “Cleaning Your Hull,” Practical Sailor, April 2018.) But you can delay their appearance on hard paint with a regular scrubbing.

Just because it is easy, don’t scrub too often. Scrubbing soft paints, even with a soft rag or gloved hand, removes some paint and dramatically reduces the life expectancy of the paint. Hard paints, on the other hand, can better withstand scrubbing, and regular cleaning can actually extend the paint’s useful life.

Wonderful review article! feeling lucky that I have found this site. very informative.