The air surrounding us on the surface of the earth weighs about 1.2 kilos per cubic meter, and when we stack up these invisible building blocks of the atmosphere, they add up to tons of pressure pushing down upon us. Its little wonder that when air at the surface starts moving sideways, it has a profound effect on sails and the sea surface.

In addition to air mass influence on sail performance, sailors have learned how atmospheric pressure trends can hint to changes in the weather. Normally, the mean pressure reading at sea level is 29.92 inches of mercury, which equates to 1,013.25 millibars. Early on, mariners learned that tracking trends in pressure paid off. These semi-random variations depict whats going on with evolving weather systems, and the barometer has become the tool of choice for measuring changes in pressure.

Over the years, the instruments design has evolved, but the information it offers has remained the same. The aneroid barometer is an outgrowth of pressure sensing using liquid columns (water, oil, or mercury) that responded to changes in atmospheric pressure.

Famous French philosopher and scientist Rene Descartes first noted the relationship between pressure in the atmosphere and the height of a liquid trapped in a closed-top, narrow cylinder that had its open end immersed in a dish of similar fluid. In Descartes experiment, atmospheric pressure, caused by the weight of the air mass above the makeshift barometer, pressed down on the fluid in the dish and forced the column of liquid to rise. Conversely, when less dense, lower-pressure air was above the dish, the liquid in the column descended slightly. This direct relationship with atmospheric pressure led 17th-century inventors and proto-meteorologists to take a close look at how the behavior of the mercury column correlated with what was going on in the atmosphere around them. Mariners of the time became interested when they discovered how such trends hinted to weather changes at sea.

With the sailors rising interest in reading the glass came a need for a less cumbersome and less damage-prone instrument. Recognizing that all surfaces feel the effect of the ocean of air that sits above us, a new crop of inventors began dabbling with small, sealed, can-like enclosures with flexible walls. These partially air-evacuated cells minutely changed shape and volume with each slight change in atmospheric pressure. The small copper or beryllium tanks were linked to dial faces via a series of levers, linkages, and sprockets. The movement of this mechanical linkage magnified the tiny variation in the shape of the aneroid cell so that the pointer connected to the linkages covered a wider arc. The better the engineering, the more accurate the relationship between atmospheric pressure and changes in the barometers reading. Mariners learned to tap the glass to help the pointer linkage overcome any residual friction that might cause the barometer pointer to stick on a reading that was either too high or too low.

A barometer can be a very useful weather predictor in temperate latitudes. Here, a constant parade of highs and lows marches from west to east, dragging along the associated ridges, troughs, and warm and cold fronts. Changes in air pressure announce the arrival and departure of such air masses, and the savvy sailor quickly learns that its not just how low or high the pressure reading happens to be that really matters, but how quickly such change takes place.

For example, low pressure is often associated with wind, rain, and building seas, while high pressure brings sunshine and a happy crew. However, too much of a good thing does not always arrive with a friendly countenance. A rapidly rising barometer can signify a fair-weather gale, conditions in which the pressure gradient is so steep that despite the fact that the sky is clear, the wind is blowing as hard as it was when the cold front rolled through, albeit from a different direction.

Each isobar represents a 4-millibar change in pressure, and when these stack up on the leading edge of a high-pressure system, it can pack as much punch as the gusts in the low-pressure system. In the Northern Hemisphere, a rapidly rising barometer heralds the passage of a cold front and is often the harbinger of cold air ushered in by a biting northwest wind. In late fall, winter, and early spring, these can deliver gale-force conditions that last for well over 24 hours.

Many parts of the world exhibit a small diurnal swing in barometric pressure that can be linked to the heating and cooling of local landmasses and the onshore and offshore winds that occur daily. This is not a fluctuation thats linked to weather changes, but one that represents a daily oscillation. When stormy weather approaches, the change is more long term and usually much greater. The fluctuation involves a drop and eventual rise, and the wind will veer (clockwise) or back (counterclockwise), according to the proximity and location of a low- or high-pressure system.

The big three trends that an experienced mariner learns to track are changes in wind direction and velocity, changes in cloud cover, and changes in barometric readings. Together, these telltales announce the approach of good or bad weather and give some indication of the severity of the approaching storms.

What We Tested

In our last test of barometers, we used the Weems & Plath Atlantis as a benchmark, and it remains a favorite among cruising sailors. (See PS September 1998 online.) Although the digital trend continues unabated, don’t give up on traditional aneroid barometers. Like the magnetic compass, the aneroid barometer has a very low failure rate, doesn’t require batteries, wireless links, or a network cable, and is still worth having onboard. During an offshore passage or race, a well-trained crew learns to record time, position, and a barometer reading when they hourly jot an entry into the log.

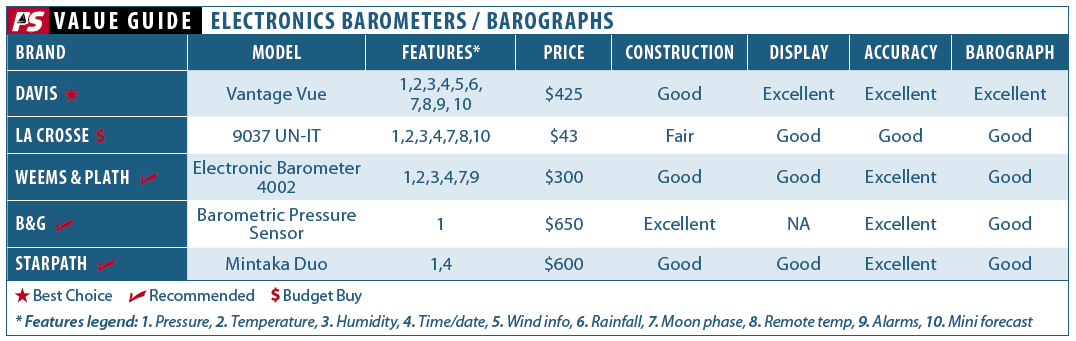

For this report, we tested three mid-range digital barometers from recognized names in weather sensing: La Crosse Technology, Davis Instruments, and Weems & Plath. Prices ranged from $43 to $425. We also looked at two other network options for receiving and displaying barographic data: one from B&G and one from Starpath.

La Crosse, like the Weather Channel, has done much to mainstream weather awareness. The weather-sensor companys user-friendly technology simplifies direct weather system measurement. Its less expensive products (under $80) use a wireless sensor to record temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure, and to send those readings back to the base unit. For more serious weather aficionados, theres a professional line of more complex gear that measures wind speed/direction, rainfall, and temperature using wireless remote sensors.

Weems & Plath is a familiar name in conventional aneroid barometers. Its electronic barometer expands on those capabilities with tracking and alarm features.

From Davis, a longtime player in this field, we tested the Davis Vantage Vue Wireless Weather Station. Although it is also a predominantly shore-based product, the Davis Vantage Vue is rugged enough to find a home on board.

Although our study focused on three examples of popular digital barometers, we also dipped into the field of networked electronic barometers that integrate with existing onboard multifunction displays, built-in barometers that are incorporated into common marine electronics, and some smartphone apps that are changing the way we monitor barometric pressure.

La Crosse

The user-friendly La Crosse 9037 UN-IT we tested is optimized as an indoor, land-based, temperature/pressure, moon-phase weather system. The single remote sensor communicates wirelessly on 915 MHz and is a big plus to users ashore, especially when placed in a backyard shed. However, a remote sensor for both indoor and outdoor data isn’t such a big deal on a boat, where the basic climate data like barometric pressure and humidity isn’t that different inside or out. Nevertheless, this is an information-rich, simple unit, and it gives budget-minded users a means of gaining barographic data without breaking the bank.

Those interested in more data will want to look at some of La Crosses higher-priced units, featuring more sophisticated sensing ability. The base stations for these units have enough computing capability to provide gust, wind chill, in/out humidity, 24- to 72-hour pressure graphing, and weather warning alerts. These higher-end units (priced from $160 to $300) can operate as miniature weather stations rather than home-based operations. The companys latest top-of-the-line unit sports a signal-emitting rainfall sensor, a solar-powered wireless wind speed/direction transducer, and a temperature/humidity sensor.

Bottom line: La Crosses 9037 UN-IT is a little fragile for marine use, but if care and creativity are used in securing it, its operation will gain sea legs. Its our Budget Buy.

Weems & Plath

The Weems & Plath 4002 electronic barometer tracks pressure over time. It has an alarm function that is triggered by rapid changes in pressure and warns of impending bad weather. The unit we tested was designed to be vessel-mounted. It will also work under internal battery power. A lead from the house bank or from the AC to DC converter is provided with the unit. It can be easily bracket- or flush-mounted, and we found its alarm system to be a handy feature, an unmistakable warning that bad weather was approaching.

The unit measures the same environmental features as the La Crosse 9037, but includes a couple of other useful features, like a race-start countdown buzzer, a gale alarm (based upon an adjustable rate of pressure change), and a handy means of connecting a DC power source. The construction quality was more rugged than the La Crosse unit; the three-level nightlight feature works well; and the unit is justifiably dubbed a marine-use instrument, but one that needs to be mounted below rather than out in the elements.

Bottom line: Our experience with the Weems & Plath electronic barometer was extremely positive. However, the setup procedure initially seemed a bit arcane. Fortunately, the toggling directions are clear enough to make the learning curve less daunting. Its Recommended.

Davis

The Davis Vantage Vue has a crisp display that gives very detailed graphic information about barometric trends and other tracked stats. The solar-powered sensor array can be mounted on a pole or arch, and cruisers sailing without masthead wind instruments will at least have useful wind data while at anchor. (The vortices off the leech of the mainsail diminish the accuracy of wind-direction/windspeed information recorded underway.)

Although its rain gauge isn’t much use on a boat that heels, the Vantage Vue system offers lots of useful weather-sensing bells and whistles beside barometric pressure. Its wireless remote sensing is capable of communicating with a base station up to 1,000 feet away using wide spectrum, frequency-shifting technology that increases data-handling speed and allows for 2.5-second updates. It has 22 user-selectable alarms. For about $150 more, users can upgrade to the more sophisticated console, the Vantage Pro 2, which delivers more detailed data and allows you to wirelessly connect to a computer via its WeatherLink software. Its a system for those more than casually interested in weather and those impacted by its changes.

Bottom line: A good combination of easy installation and sea-ready ruggedness, the Davis Vantage Vue is our Best Choice.

More Electronic Barographs

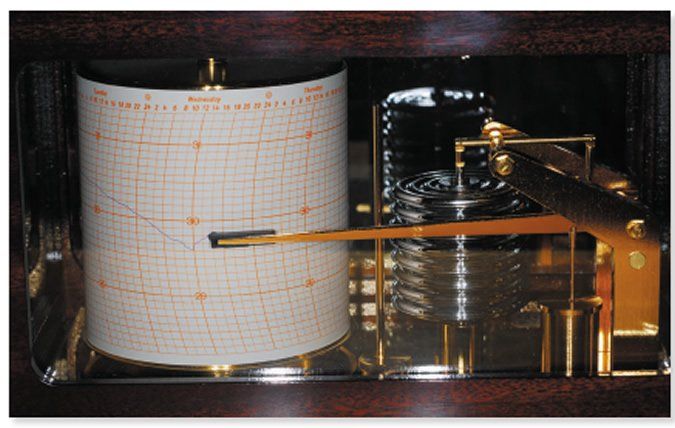

The old mechanical barograph remains more than a sidelined conversation piece. Kept inked and wound, it tirelessly tracks the perturbations of the atmosphere. Mechanical barographs are basically a bellows-like aneroid tank with an ink-laden stylus at the end of a linked lever arm, and their clockwork-driven drum rotates a cylindrical paper graph that displays pressure changes over time. Many have been sidelined by electronic barographs like Clipper MeteoMan ($305) and Aquatechs DBX 1 ($500). The switch to electronic readouts is partially because of the classic barographs price tag ($1,000 or more), and partially due to the no-ink-hassle operation of electronic sequels.

Bottom line: If a barograph is what you are looking for, the Starpath School of Navigation offers a Mintaka dual-sensor barograph ($595) thats compact, accurate, and simple to operate. In our opinion, it offers a good blend of features and pressure trend display. We Recommend it.

Network Barographs

In addition to the standalone electronic barometer/barographs that we tested, we also liked the B&G approach, which allows users to record real-time pressure trends and compare them with weather analysis and forecasts received via Sirius radio. They offer a barometer transducer thats a sequel to other plug-ins in their lineup such as depth-sounder transducers, wind-instrument sensors, or temperature-measuring probes. The pressure-sensing transducer (690-00-007) sends a B&G Zeus multifunction display a string of code accurately depicting real-time pressure, and time-based changes can be displayed in bold, graphic detail.

Bottom line: Those with a B&G system on board should look into the barometer sensor option-if the discount house price tag of $642 is in the budget. Recommended.

Smart Phones, ETC.

There are also some interesting alternative ways to capture electronic barometric readings. Among the take-your-own-readings regime are sensors that turn a smart phone or tablet computer into a weather station. Products like the indoor and outdoor sensors from Netatmo Weather can be set up to electronically link to your phone or tablet. Incidentally, the new iPhone 6 has built-in barometric sensing capability. Even Simrads two versions of RS-25 VHF radios have built-in barometer-sensing capabilities that allow a user to scroll to a real-time pressure reading and pull up a profile of how the glass has been trending over the last 24 hours.

Not only are we seeing more and more electronic equipment capable of measuring atmospheric pressure, but sailors are surrounded by a fleet of buoys from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association that are keeping track of the ever-changing sea surface air pressure. Simply listen to local VHF weather broadcasts or pull up the National Data Buoy Center webpage (www.ndbc.noaa.gov), and youll get a nearby buoy reading. Just make sure you note the time that the observation was made.

Conclusion

In our testing, we found that electronic barometers and barographs, like their mechanical antecedents, need to be checked to make sure that they coincide with an accurate pressure reading at a nearby official National Weather Service weather station. Just go to the National Data Buoy Center online, and select the closest weather-reporting buoy or shore station. Follow the manufacturers guidelines on how to set your barometer mechanically or electronically, and use the most recent pressure reading of the buoy nearest you.

In settled weather, a 10- or 15-minute lag between the current time and the time of the reading at the respective buoy will not make any difference.

Its mostly a matter of choice as to whether you track atmospheric pressure trends in inches or millibars. Incidentally, the latter is equal to hectopascals (hPa), and some scales use it as the metric reference. Those who sail in other parts of the world will quickly discover that the millibar reading is the scale of choice. Whichever scale you prefer, keep in mind that its the rate of change that defines how much wind will soon be causing the rigging to hum.

So whether youre a purist with a Fischer aneroid barometer who manually logs readings each hour or youve chosen a Weems & Plath electronic barometer, Starpath Mintaka Duo, or have hitched up your B&G Zeus to a pressure sensor, what you will get is accurate, time-specific pressure readings. The B&G interface offers an impressive barograph display, but the lower-priced gear still affords useful plots of pressure trends. It seems clear that as technology evolves, we can expect more ways to interface sensors with a variety of displays-whether they are MFDs, laptops, digital tablets, or smart phones.