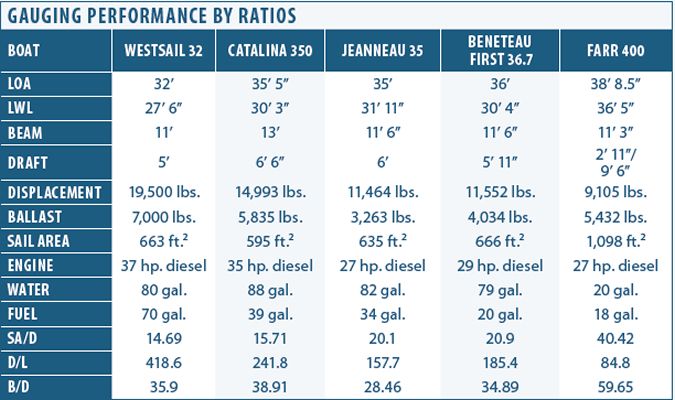

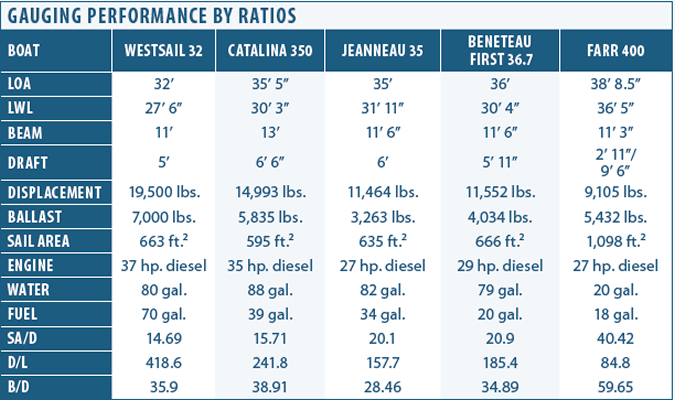

Sailboat performance varies based on the eye of the beholder. Racers want light-air alacrity and a willingness to plane while cruisers want directional stability and reasonable speed with moderate sail area. A boats design dimensions and a few simple ratios give some hints about these attributes.

Most performance-oriented boat designs focus on around-the-buoy racing; these assume that there will be a large crew to keep sail area and trim optimized and to provide movable ballast and that the boat must cope with windward and leeward legs of a race course. Offshore, point-to-point race boat designs are greatly influenced by racings handicapping rules. In either case, these rules penalize performance, and design factors like ultra-wide beam-intended to leverage crew weight for righting moment-are of little value to shorthanded cruisers. Make sure that the boat youre looking for is fast in the context under which it will be sailed.

The sail area-to-displacement ratio (SA/D) compares energy and resistance-much like a horsepower-to-weight comparison in an automobile. As the SA/D ratio grows higher, so does the vessels potential speed under sail. However, too much sail area and too little righting moment means a very tender boat. Too little sail area and too much displacement means you can brag about carrying full sail in 20 knots, but your boat will move like a sea buoy in 7 or 8 knots of breeze.

The ballast-to-displacement ratio (B/D) of a boat tells you how much secondary righting moment to expect from the keel. The smaller and lighter the vessel, the more important it is for this number to be higher for stability as well as for performance reasons. Bulbs and other keel-tip shapes lower the vessels center of gravity (CG) and can lessen the need for a 40-percent B/D ratio. A deeper draft can also lower the CG and can improve on-the-wind performance.

A boats displacement-to-length ratio (D/L) has a lot to do with the resistance of a hull shape moving through the water, and since skin drag is the big enemy at lower speeds, the D/L ratio tells us a lot about a boats light-air performance. By increasing the boat length and keeping the displacement the same, decreasing displacement, or doing both, the D/L ratio decreases, and the boat will go faster in light air. Wave-making kicks in as the major resistance at higher speeds, and the implications of the D/L ratio lessen.

In a nutshell, when it comes to performance under sail, light displacement is fast; deep-keel boats point higher and sail more efficiently to weather; full, flat sections aft cause a boat to plane sooner; and more sail area delivers more power. When it comes to delivering the goods in an open-ocean context, seakeeping ability is an important factor in performance as is the amount of punishment the boat and crew can endure.

Ordered by sail-area-displacement (SA/D), this table illustrates a progression from a heavy-displacement cruiser (Westsail 32) to a fast and light racer (Farr 400). Note how the designers altered ballast, sail area, and displacement to reach their goals.