The underappreciated winch is a sailors best friend-and if Sir Isaac Newton was around today, he would give the ubiquitous selftailer a nod of approval. Yacht designers, naval architects, and mechanical engineers have put Newtons mechanical principles to good use, and the handy hardware offers a lesson in mechanical energy transfer.

Newton would be especially pleased with the current array of manual winches: simple machines that transfer rotary force into a straight-line pull. Sailing is all about tensioning and easing lines, and ever since the first ratchet-controlled drum on a spindle made its way aboard the Americas Cup sloop Reliance in 1903, theres been a concerted effort to improve input-to-output efficiency.

In this first installment of a two-part look at winches, we present an overview of market trends, an in-depth look at two product innovations, and a retrospective look at how some of the older technology has been holding up.

Background

Early sailboat winches were little more than a lever-rotated, rod-and-spool contrivance with pawl-like teeth ensuring one-way drum rotation. The winch handle behaved as a rotary lever, and with no gearing involved, the power ratio was simply calculated by dividing the winch handle length by the drum radius. Each rotation of the handle resulted in a full rotation of the drum, and the sheet or halyard moved a distance equal to the circumference of the drum (Pi x drum diameter). Eventually, gears were added, and now two-, three-, and even four-speed winches augment line hauling.

These ratio changes, afforded by varied-diameter gearing, are a sequel to an automobiles transmission. However, in this case, the engine is the sailor grasping the winch handle, and attaining more horsepower requires more gym time.

Bronze bushings were originally used to lessen friction at the drum-to-spindle interface, and the net effect was an increase in line-pulling power. The single-speed antiques made clicking sounds as the drum rotated clockwise and held fast as line tension tried to turn the drum in the opposite direction. The same ratchet concept is used today, but bearing sophistication includes ball, needle, and roller bearings of metal and composite materials. Winch-derived hauling power eclipsed what was gained with a block and tackle, validating Newtons mechanical principles and plummeting block and tackle sales.

Figuring efficiency

Its easy to put some empirical numbers to winch efficiency. For example, a 10-inch winch handle turning a 2-inch-radius rope drum yields a 5-to-1 power increase. It also causes a five-fold decrease in the rate of line movement (the no free lunch rule). This example is based on a non-geared, one-speed winch. Theoretically, we can assume that 35 pounds applied at a right angle to the winch handle would turn into 175 pounds (5 x 35) of line tension. If we want more pull and are willing to put up with a little less line-hauling speed, we could upgrade to a 12-inch double handle winch handle that would give us a 6-to-1 ratio. The double-handle grip would allow us to up our human power input to 45 pounds of rotary force. So, with a greater ratio and more force, we up the torque going into the winch, and the result is a 65-percent increase in line pull (6 x 45 = 270 pounds).

The power-ratio calculation also involves the gear ratio, which functions to lower or raise the line retrieval rate in order to increase or lower pulling power. In essence, you can design a winch with a ratio that hauls a sheet in faster or you can design the winch to pull harder, but you can’t do both at the same time while keeping the input energy constant.

The simple formula to calculate the power ratio of a geared winch is (winch handle length x gear ratio) / radius of drum = power ratio. The power ratio times the force applied to the handle gives the theoretical output pulling power of the winch. Sadly, we must also factor in the role of friction, a fact of life in all mechanical systems. Its a downside that gets worse as a winch approaches its load limit, as time and poor maintenance wear out bushing surfaces, and as salt and grit invade the spaces between moving parts.

Some years ago, we watched a singlehander bring a traditional, heavy-displacement cutter alongside and use a spring line led to a cockpit winch to nudge her the final bit. The winch was an ornate bronze artifact, and just as he started to haul in the spring line, the modest bit of tension caused his winching effort to stall, and the handsome chunk of bronze delivered negative mechanical advantage. We later had a chance to autopsy that winch and discovered that overly narrow, small-diameter, solid-bronze spindle was slightly bent and was to blame,.The drum spun nicely when no load was applied. But as soon as tension built up in a sheet or docking line, the skirt of the drum was forced against the non-turning base, creating a brake-like effect rather than the smooth spin of a roulette wheel. The winch industry has responded to such design flaws with stronger shaft material and better spindle and tower designs; some have even added bushing or bearing surfaces to the drum skirts.

Market Snapshot

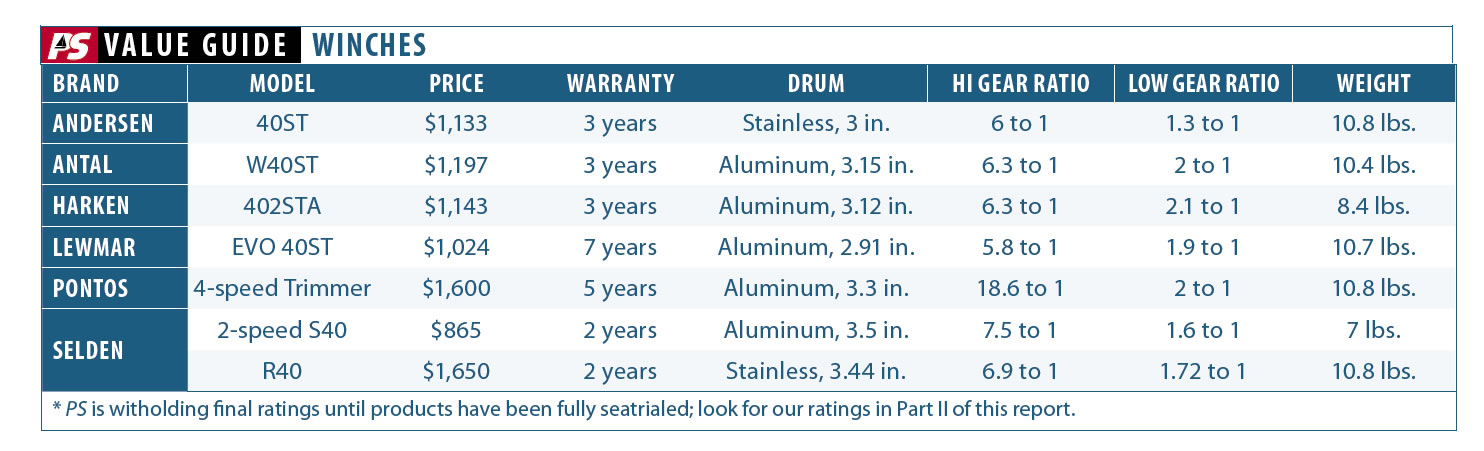

In researching this report, we were surprised to see quite a few winch upgrades, improvements in efficiency, and downright major advancements in a technology thats been around for over a century. Testers evaluated current winch offerings from marine hardware makers Andersen, Antal, Harken, Lewmar, Pontos, and Selden.

Made by the Denmark-based Andersen Winches, the 40ST winch comprises a stainless-steel base, drum, and spindle. The drum, which contains vertical ribs rather than an abrasive surface, is fabricated with an aluminum bronze core, the same material that the upper base plate is made from. Isolating various dissimilar and galvanically reactive metals has become an artform, one that Andersen seems to have mastered.

The drum ribs add enough line friction-and do so with less abrasion than conventional knurled and abraded drum surfaces. Testers found that Andersens Power Rib drum makes sheet easing and tensioning an efficient process.

Italian manufacturer Antal has a full lineup of conventional and self-tailing winches. Its W40STAL has a nicely sculpted anodized aluminum drum and an aluminum base cut using Computer Numerical Control (CNC). Antal uses a 316 stainless-steel spindle, bronze gears, and roller bearings. The line lead and self-tailer are ergonomic and provide efficient sheet handling for line diameters ranging from 8 to 14 millimeters. The drum is also available in bronze and chrome bronze.

Based in Wisconsin, Harken has been a major player in winch development ever since it brought the Barbarossa line to the U.S. Today, its offerings range from the tried-and-proven Radial to the competitive edge Performa, which is favored by many racing sailors. The company also services the esoteric, ultra tech, carbon-fiber winch, custom boat end of the spectrum. For this comparison, we tested-and liked-Harkens mainstream, diagonal-rib, aluminum drum 40.2STA with composite self-tailer jaws and 17-4 PH stainless-steel gears and pins. This winch model handles 8 to 12 millimeter line and also comes in a chrome bronze drum alternative.

Lewmar hardware is a British tradition that for decades has held sway in the U.S. market. Its winches once stood alongside Barient, Barlow, and Barbarossa, but with the B-team now gone, Lewmar is holding its own with a new crew of innovative winch makers. While many manufacturers are moving toward molded plastic composite winch parts, Lewmars Evo line, an update of its Ocean series, retains a bronze frame and tower, bronze gears and pawl assemblies, and a stainless-steel drive spindle. Caged, stainless roller bearings ride on the bronze spindle housing. The drum (available in several materials) simply slides over the central spindle, and a robust bronze drive gear engages with a toothed ring surrounding the lower, inside portion of the winch drum.

Swedish hardware and spar maker Selden is known for its effective use of investment-cast stainless steel throughout its hardware lineup. Its popular S40 two-speed winch is the lightest one weve found in this size range thanks to Seldens use of aluminum alloy and composite plastic parts. Disassembling the winch, we discovered a composite skirt covering the drive gears and a cast alloy base frame. A composite portion of the vertical tower was held in compression by two, long, stainless-steel machine screws, and the alloy drum rotated as drive gears delivered torque to the drum via contact with a toothed ring on the internal side of the drum skirt.

We last looked at two-speed, self-tailing winches in the June 2006 and Aug. 15, 2000 issues; in both of those tests, stainless-drum winches from Andersen (No. 40 and 28ST) were the top picks.

Topping our innovation list

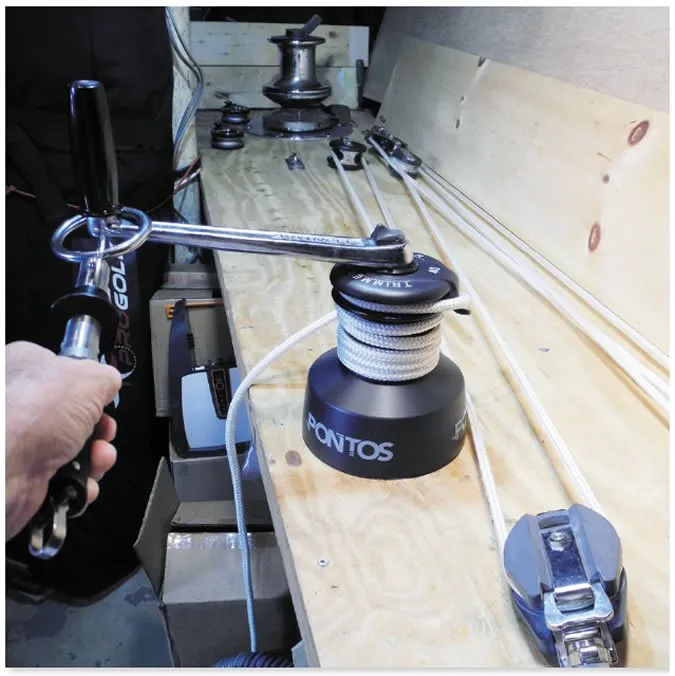

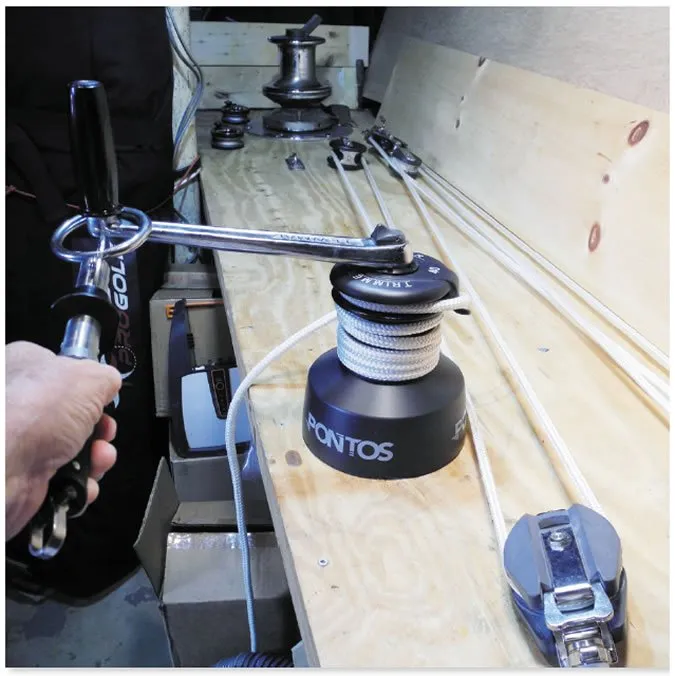

Pontos is a French winch design built in Italy thats been making waves around the world. After we got our first look at the Pontos winches during the Annapolis Sailboat Show, the company loaned us two models to disassemble and bench test for this report. Both are about the size of a two-speed conventional 40 winch, but each incorporates a four-speed, auto-shifting gear train. The big difference between the two self-tailers is the rate at which they can haul line.

The Trimmer model is all about pull power, while its cousin, the Grinder, has an overdrive initial speed that hauls in line at a blistering rate of 2.6 drum circumferences of line per rotation of the winch handle. (Thats up to five times faster than some similar-sized, two-speed winches.) Turning the handle in the opposite direction delivers a slower .75 drum circumference of line per rotation of the winch handle. And when the energy it takes to crank the handle exceeds about 25 pounds, theres a clicking sound, and the winch automatically downshifts, offering two even lower gear ratios that deliver slower rates of line retrieval but generate greater pulling power. In our testing, we found that it took 19 pounds of handle pull to create 500 pounds of sheet-hauling tension. The Grinder is the right choice for a racer looking for fast ,on-the-fly jibes and quick trims after a tack. (Plus its a great way to tire out a teenage crew.)

The Trimmer is a shorthanded cruisers dream come true. In our duplication of the low-gear tension test mentioned above, we were able to reach 500 pounds with just under 8 pounds of tension on the winch handle. The tradeoff is at the other end of the scale where fastest retrieval rate is a virtue. The Trimmers top end gearing is a relatively standard two rotations of the winch handle to haul in one drum circumference of line. This is just fine for a cruiser whos much more interested in getting more for less when it comes to sheeting home the big genoa or getting real tension in a mainsail halyard.

Not only are the Pontos winches solid performers, but they are engineered and built with a critical eye to detail. Machined bronze and stainless gears mesh with a careful fit, and the unique, torque-sensing shifter rises vertically on the spindle housing as handle pressure increases. The auto shift occurs at the right time (about 25 pounds of handle pressure), and if sheet tension decreases-resulting in a big reduction in the force it takes to turn the winch handle-the unit will auto shift back into the high range.

Testers also found that the drum surface offered a good grip but did not present an overly abrasive surface. The line lead and self-tailing jaws made wrapping and releasing a sheet quick and precise. Testers liked the ease with which the winch came apart and the straightforward reassembly process. One of the more unique features was the ring-type, roller-bearing race that fit into the bottom of the drums inner skirt. It provided a large-diameter bearing support in a region that often deforms under pressure.

Selden also earned innovation recognition for its reversible, two-speed R40 winch, which is well engineered, well constructed, and operates as advertised. Testers liked the investment-cast stainless frame and drive-gear holder, along with the stainless-to-stainless line lead locator. During testing in low gear, the 500-pound line tension threshold was crossed with the spring gauge on the winch handle reading only 16 pounds.

Not all sailors need a winch that can ease as well trim a sail with the sheet left in the self-tailer. But those who sail shorthanded and take proper trim seriously will find the pushbutton in the center of 40Rs custom winch handle to be a handy aid. Depressing the button turns winch cranking from the usual trimming function to a controlled ease. This allows a shorthanded crew to quickly respond to each minor oscillation or course change.

Conclusion

Winch design continues to evolve, and some of the latest trends hold significant value to consumers. However, looking back at some of the successes of the past, one can’t help but note how much longevity was, intentionally or unintentionally, built into older products. Replacement parts remained available, and with a set of bearings, pawls, and springs, many an old relic lives on.

When choosing a new winch, look for its Achilles heel. It may be a top-cover screw with an odd-sized fine thread or a plastic part that just might shear. Invest in an extra set of highly vulnerable parts, and if youre headed to sea, make sure you have the tools to replace them.

Stay tuned for our bench test report and a closer look at the winches profiled in this article.

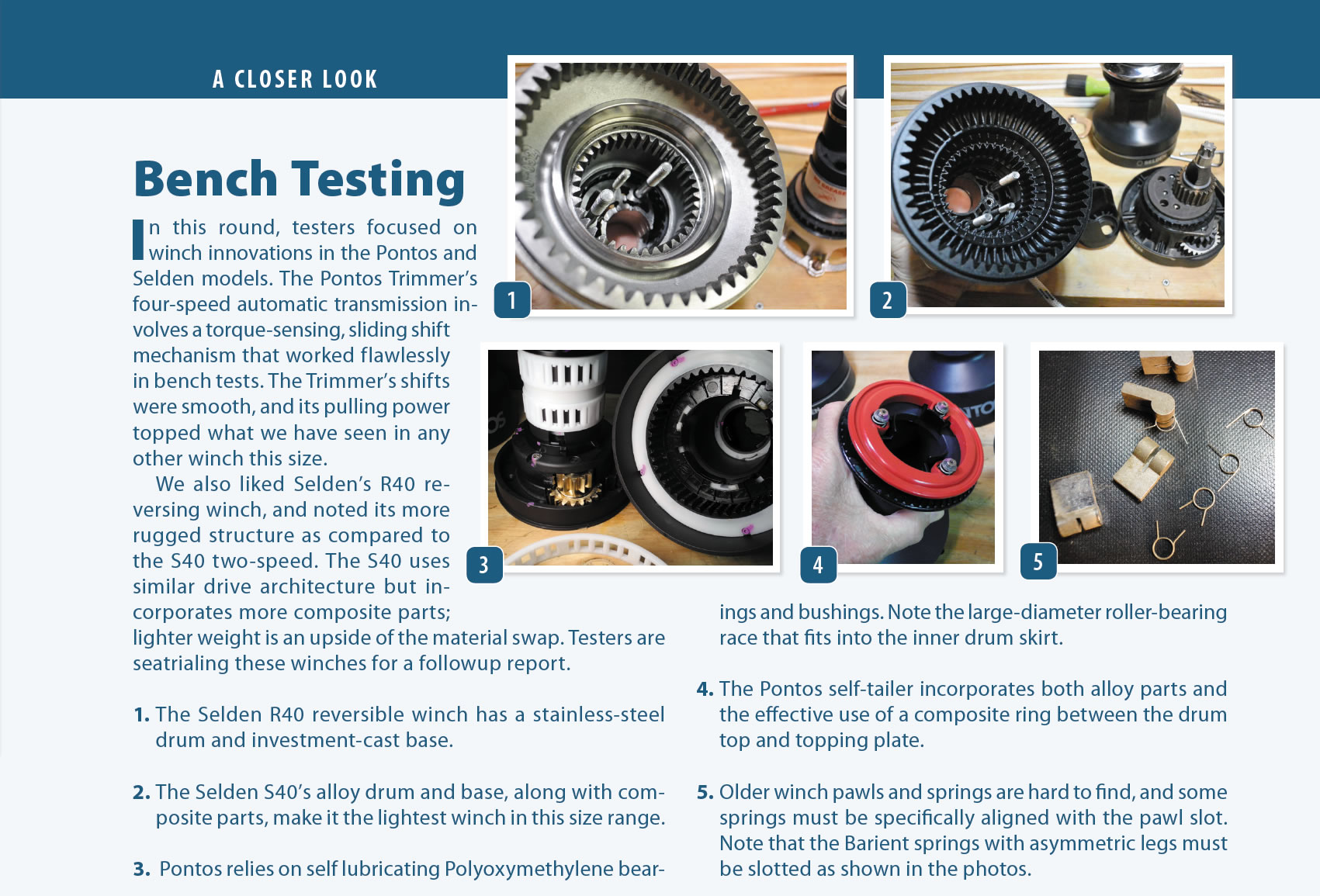

In this round, testers focused on winch innovations in the Pontos and Selden models. The Pontos Trimmer’s four-speed automatic transmission involves a torque-sensing, sliding shift mechanism that worked flawlessly in bench tests. The Trimmer’s shifts were smooth, and its pulling power topped what we have seen in any other winch this size.

We also liked Selden’s R40 reversing winch, and noted its more rugged structure as compared to the S40 two-speed. The S40 uses similar drive architecture but incorporates more composite parts; lighter weight is an upside of the material swap. Testers are seatrialing these winches for a followup report.

1. The Selden R40 reversible winch has a stainless-steel drum and investment-cast base.

2. The Selden S40’s alloy drum and base, along with composite parts, make it the lightest winch in this size range.

3. Pontos relies on self lubricating Polyoxymethylene bearings and bushings. Note the large-diameter roller-bearing race that fits into the inner drum skirt.

4. The Pontos self-tailer incorporates both alloy parts and the effective use of a composite ring between the drum top and topping plate.

5. Older winch pawls and springs are hard to find, and some springs must be specifically aligned with the pawl slot. Note that the Barient springs with asymmetric legs must be slotted as shown in the photos.