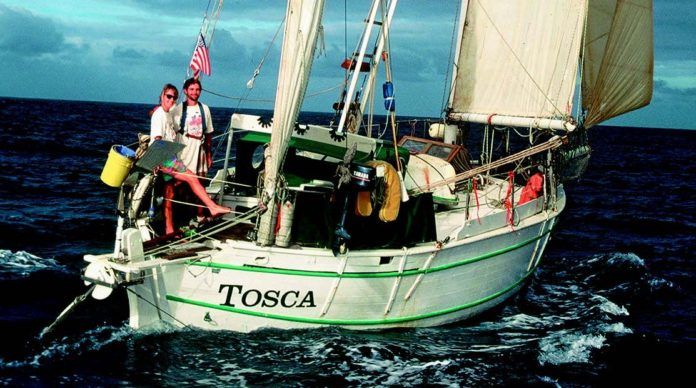

I feel for the crew of Tanda Malaika, a family of six whose 46-foot Leopard catamaran was lost on a reef on the southwest corner of Huahine in French Polynesia in July this year. The loss is especially acute because, as the captain himself points out, it could have been avoided. The account of the wreck, provided by the skipper/owner Dan Govatos, and recorded in the podcast Slow Boat Sailing offers important lessons for cruising sailors.

The first error Govatos made was in planning the 80-nautical mile passage between Moorea and the anchorage Huahine. Anticipating the forecast winds of 20 knots from astern for most of the passage, he estimated about 10 hours for the passage, an average speed of 9-10 knots putting their arrival at 4 p.m., with plenty of light to enter Huahines reef pass. When the winds didn’t materialize, the crew ended up motorsailing for much of the passage-not reaching the southwest corner of Huahine until 9 p.m., well after dark. To complicate matters, the strong trades finally kicked in that night, creating an uncomfortable ride as they approached the island.

Lessons: Be extremely conservative when estimating speeds for a passage. It is much better and err on the slow side. You can almost always slow down or even heave-to, but it is much harder or impossible to make up for lost time. Likewise, allow a healthy margin for error in weather forecasts, particular in areas where meteorological data is spotty.

The second error was in the actual navigation. As the winds increased, Gavatos steered the catamaran close to Huahine and its steep-to fringing reef to get some shelter from the sea. According to him, the Navionics charts he was using misplaced the reef by about 1/4-mile. So instead of 200 feet of water, they found themselves on the reef.

The atolls and volcanic islands of the Pacific rise steeply from the ocean floor, offering little warning. As our special report on navigation pointed out (see GPS Accuracy Can’t Replace the Navigator, PS July 2015) even charts of more thoroughly surveyed errors can have gross errors that put sailors at risk.

As Gavatos relates, he saw the sounder indicate 85 feet and then decrease intermittently from there. At first, he assumed the sounder was incorrect-that some anomaly was creating a false reading (as had happened before).

Lessons: When navigating unfamiliar coral reefs at night, 1/4-mile is cutting it far too close. Better to stand well offshore one mile or more (some reefs are mis-charted by more than one mile). If you absolutely must hug the reef (dangerous) or tuck behind for a lee (also risky), you’ll want multiple navigation sources to confirm your position-your own senses being among them. Eyes and ears on deck. You’ll need a better reason than it’s “more comfortable” to expose yourself to the added risk. it’s safer just to stay clear. Closed cockpits on big cats can take your senses out of action, a potential handicap during landfalls (see Multihull Special Report, PS August 2017).

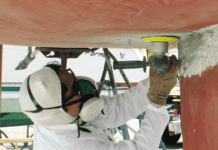

Although some boats can be salvaged from reefs, the Leopards cored laminate, an imperative on most multihulls, had no chance against the impact of a reef. I can only imagine the heartbreak of the crew as it filled with water.

For the average cruiser, the half-day passages are the hardest to plan. The temptation is to leave early and knock it out in daylight, but as the crew races against time, exhaustion can set in and the bad decisions multiply. Very often a better option is a night sail, leaving plenty of daylight hours to navigate into the new port.