When Hurricane Irma plowed through the Florida Keys, it left behind both a trail of destruction and a wealth of information for us to learn from. One of the most instructional episodes took place at the municipal mooring field at Boot Key in Islamorada.

Installed in 2006-2009, the fields 226 helix (screw-type) moorings were fitted with special elastic downlines. As Irma approached, there were 220 boats secured to them, facing the full brunt of the storm. Fifty-four boats stayed on their moorings, and the rest ended up sunk, on the beach, or in the mangroves. A number of boats anchored nearby also dragged through the mooring field, adding to the damage.

Only two helix anchors failed, a testament to conservative engineering and good installation. One anchor snapped seven feet below the sand, well into the coral rock below, after two boats drifted back on the tenant boat.

None of the elastic StormSoft downlines failed. Combining the strength and chafe resistance of polyester with the elasticity of rubber, the downlines at Boot Key have a tensile strength of 24,000 pounds and the ability to stretch from 13 feet to about 17 feet under storm conditions. (StormSoft downlines physical characteristics can be varied to suit the location).

Photo by Carolyn Shearlock

The downlines were linked to 8-foot by 1-inch nylon three-strand pendants. Four of these failed, either due to other boats drifting down on the tenant boat and overloading the pendant, or the pendant chafing through when it snagged on an anchor or roller.

The boat is attached to the 1-inch diameter pendant with an owner-provided pendant no more than 8 feet long. Not surprisingly, this final link, the area that experiences the most chafe, was where failure typically occurred. The StormSoft downlines, and one-inch nylon pendants were exceptionally reliable.

Failure Analysis

To focus on preventable failures, we discarded losses that occurred when another boat dragged down on the lost vessel. The remaining failures occurred either because the cleats pulled out of the deck (about ten boats), the pendant was overloaded, or-as in more than 90 percent of the cases-the pendant chafed on some surfaces of the boat.

Was the force transmitted to the yachts simply too great? A few boats had their cleats ripped from the deck. If we compare the American Boat and Yacht Councils nominal working load limit for a 1-inch nylon pendant (2,795 pounds) and its working load limit required for the deck fittings for mooring a 35-foot yacht (2,700 pounds), the two are fairly matched. This suggests that there would have been more pendant failures if the loads had exceeded the ABYC basis by a significant amount.

However, as Practical Sailors past tests of actual rode and snubber loads revealed, the real-life loads at various windspeeds is generally much less than the ABYC predictions (see Anchor Snubber Shock Load Test, Practical Sailor November 2013 and What is Ideal Snubber Size, March 2016). In reality, the ABYC standard is conservative. It includes both an 8:1 safety factor for nylon rope and about a 2:1 safety factor for its deck fitting working loads.

Often the limiting factor related to hardware is not strength, but size. How many 35-foot yachts have cleats and chocks that can accommodate 1-inch nylon rope with chafing gear, and how many have cleats and backing plates have a breaking strength of 10,800 pounds (four times the anticipated loads based on the ABYC data)?

In fact, most 35-foot production yachts can accommodate only 5/8-inch line plus chafe gear. One smart alternative is to use a bridle, which splits the load between two cleats. However, yawing puts most of the load on one leg of the bridle, requiring a design load of approximately 75-percent of 2,700 pounds-and that still requires 7/8-inch rope. The logical answer to the abrasion-strength dilemma is to use a short length of abrasion-resistant Dyneema where the pendant passes through the chocks (more on this later). But that still does not solve the cleat strength issue.

What is the actual storm load on a 35-foot yacht? The wind load alone, based on Practical Sailor testing and that of many others (see Anchor Testing and Rode Loads, May 2012) is probably about 25 percent of the ABYC value in the adjacent table Estimated Mooring Loads. However, the wind speed that the ABYC uses to estimate storm loads is 60 knots. The estimated wind-only load at 100 knots would be about 1,875 pounds-without any waves.

When you add wave height and account for the very short scope (about 2.5:1 to 3:1, depending on freeboard, water depth), you could expect frequent peak loads of up to 4,000 pounds. Four-thousand pounds of load is not enough to cause widespread failure of one-inch nylon pendants, particularly not when they are connected to more vulnerable owner-supplied pendants, but it does exceed the ABYC limits that guide builders.

We don’t know the actual forces that the boats in Boot Key experienced during Irma, but it seems probable that the forces transmitted to the boats did not greatly exceed the ABYC guidelines for loads in a storm wind. Any attachment points that did not match the ABYC standards would break or tear away from the boat if the pendant itself did not break. This is a graphic reminder that ABYC specs, like most that guide the marine industry, are minimums.

Florida Mooring Laws

Florida leaves it up to the engineers to decide what works in its General Permit to Local Governments for Public Mooring Fields. The rules state: Vessel mooring systems and the installation plans must be designed by a Florida registered professional so that the mooring systems with vessels attached withstand, at a minimum, tropical storm force winds and so that the associated tethers, lines, and buoys do not scour or damage the bottom. The mooring system and associated tethers, lines, and buoys shall be maintained for the life of the facility.

Although tropical storm force winds are used as the baseline for the moorings at Boot Key, the post-Irma assessment suggests that these mooring systems are capable of withstanding more severe conditions and meeting a higher standard.

Maintenance requirements are a separate matter. The moorings are visually inspected after each storm, but unless they are physically damaged, the downlines and pendants remain in place. In the end, four downlines and 15 pendants were replaced due to wear. All the replaced downlines met their engineered strength in post-storm tests. For all her power and fury, Irma had little effect on the strength of the downlines.

The Enemy Chafe

When you eliminate the outliers, virtually all of the boats broke loose because the owner-supplied portion of the pendant failed. In some cases, the line was undersized. In other cases, there was simply no chafe gear, or it slipped out of position. In some cases, the pendant got hooked on the anchor or anchor roller when the boat pitched, and then chafed. Our recommendations:

Strong pendant. Look up the ABYC mooring load requirement for your boat. This is probably considerably larger than your anchor rode or docklines. You may need to switch to Dyneema rope in order to fit a rope of the required strength through the available chocks. Evaluate your cleats and backings to see if they are up to the task.

Chafe protection. Nearly all (95-99 percent) of failures were due to chafe. Although many pendants come with a moveable chafe guard about 18-inches long, we like the idea of covering the first 6 feet with a continuous covering of reinforced chafe protection. (See Round Two: Chafe Gear for Mooring and Dock Lines, PS October 2012 online).

A longer pendant is better. Even if the mooring is strong, scope increases shock absorption and allows the bow to rise more easily with the chop. For boats from 35-50 feet, 15 feet is a good starting point. Some marinas will allow only 8 feet, in the interest of limiting swing circles.

Use a bridle. As the boat pitches, the bow roller, the anchor, and bobstay will chafe without a bridle. A bridle will also limit yawing, which will reduce loads and limit any abrasive motion of the pendant in the chocks. Because it is very likely that one leg will intermittently carry nearly the entire load, the line should be only slightly smaller diameter than what is required for single-line arrangement.

Remove the anchor for major storms. And while you are at it, set up a temporary guard to prevent the bridle line from hooking on the edge of the bow roller. If the pendant passes over the roller, a pin should restrain it from jumping out of the roller and the anchor must be removed.

Double pendants. Attaching two pendants equipped with thimbles to a single shackle can cause chafe. A better approach is to use a Dyneema soft-shackle or strop to combine the pendants and attach them to the shackle (see Reassessing Eye Thimbles, page 11).

Attachment to the mooring pendant. For overnight mooring it is common practice to simply pass the ships mooring line through the mooring pendants eye-an invitation to chafe. The boats mooring line should be a attached with either a steel shackle (with a thimble to prevent chafe), or by luggage-tagging a spliced eye (soft-shackle) made of Amsteel.

U-bolt on the stem. Many catamarans and some monohulls feature a well-engineered U-bolt, or eye at the stem. During storms this can provide a truly chafe-free and strong attachment point. When properly engineered, these have proven very reliable

Minimize chafe at cleats and chocks. If the cleats are within a foot or so of the chock, good chafe gear should suffice. But if they are 3 to 5 feet away, run short leader of Dyneema or a similar high modulus polyethylene (HMPE) through the chocks to the nylon pendant. This prevents friction at the chock caused by stretch. Chafe gear is still required.

Be careful with HMPE. Don’t use an all-Dyneema pendant unless the mooring system is designed for this material. The material is strong, but its lack of elasticity increases the chance of shock loads, especially during a storm.

Conclusion

It’s always best to get out of the way of other boats if you can’t flee a hurricane. If a mooring field is your only option, make sure the moorings are inspected and try to understand the characteristics of the mooring and the location.

If the boat will be on a mooring through real storms, evaluate your mooring cleats and chocks; they are the most important part of your boat. They must be strong, well designed, and probably larger than supplied from the factory. Your pendant must meet ABYC permanent mooring requirements, be exceptionally well protected from chafe, and if the boat is exposed to much weather at all, should be replaced every year, or at least every other year and after every serious storm.

What about the design of the moorings themselves? The durability of helix moorings is undeniable. We are still concerned about the forces transmitted to the boats and are looking forward to future advancements from downlines and pendant manufacturers.

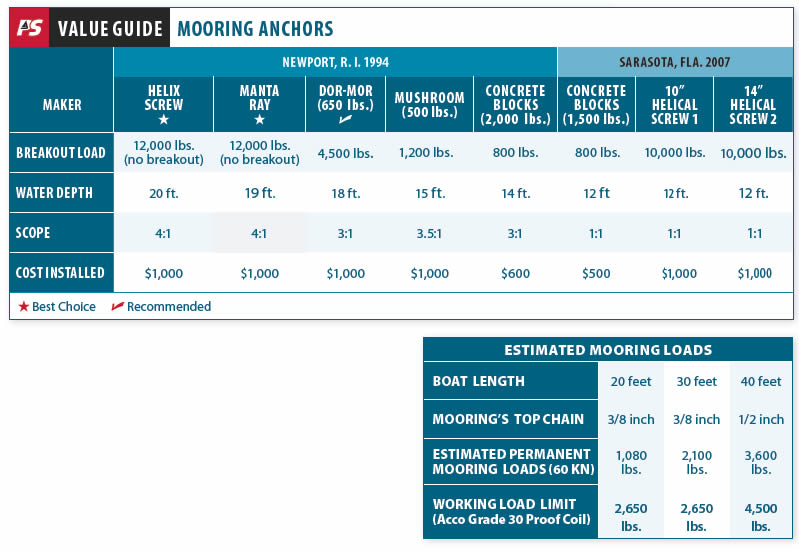

Despite the success of elastic moorings, most moorings are still chain. The table at right, offers estimated normal mooring loads based on Table 1 Design Loads for Sizing Deck Hardware, in section H-40, Anchoring, Mooring and Strong Points, of ABYCs Standards and Technical Reports. Chain working load limits are based on data from chain maker Acco. The right chain size can vary greatly depending on the boat, harbor, and other factors.

Not surprisingly, nearly all of the failures involved chafe at the owner-supplied pendant. In addition to good chafe gear that stays in place, new high-quality rope is important.

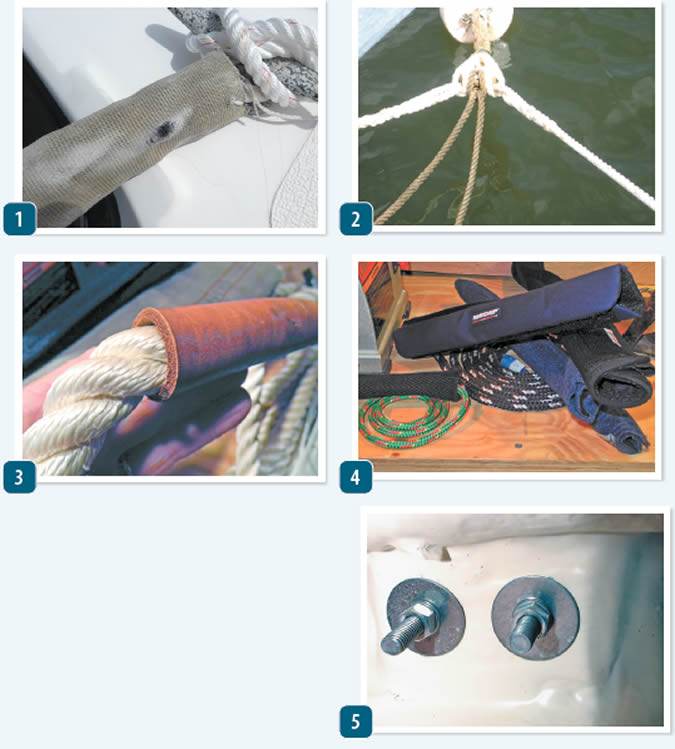

- Double-jacketed fire hose, typically made of nitrile rubber and woven polyester, protected the new three-strand 5/8-inch pendant on Carolyn Shearwater’s Gemini Catamaran.

- A set of back-up lines (center) were led to the boat to reinforced points on the Gemini and left slack.

- Sewn leather chafe gear 3/16-inch thick performed well in our chafe gear test and was one of the least expensive choices (see Practical Sailor October 2012).

- Fjord’s line of heavy-duty chafe protectors offer hook-and-loop closure for easy attachment, even while the line is already in use. They performed outstanding in our chafe protection abrasion resistance test (see Practical Sailor October 2012.)

- Although fender washers can meet ABYC requirements, and they might be adequate to support storm loads on smaller boats, our testing indicated that they are no substitute for a proper backing plate (see Practical Sailor, August 2016).

The system is great but try to get a rode or even an eco band thimble and you will be sorely disappointed. Once you have the system you can’t get parts and your mooring is useless. Be careful when you install this system

It seems that with helical mooring the preferred pull is straight up which would argue for shorter pendant. But none of the articles I’ve seen so far talks about pendant length specifically for helical mooring. Many articles argue for longer pendants to pull sideways instead of straight up on the mooring, but that seems contrary to the physics of how helical mooring work.

Do you have experiences and thoughts on this?

Sincerely

Xavier