Whether you want to cruise the higher latitudes or extend your sailing season this winter, you’ll need to think about clothing. Over the years, Practical Sailor has published a number of tests and reports on garments that we can count on to keep us warm when the wind chill dips toward freezing. In this report, we’ll take a broader look at the essentials, focusing on the first principles; under layers, accessories, how to wear them, and what materials stay dry.

As a supplement to our previous reports on the various categories of individual garment (hats, gloves, under-layers, boots, foul weather gear, etc.), this study focuses on field trials and the experiences of high-latitude sailors, including racing teams, adventurers, commercial mariners, and Practical Sailor contributors who have decades of experience sailing in the cold. As much as possible, we’ve looked for affordable, time-proven alternatives to the often over-priced tech clothing.

THE BASICS

Staying warm isn’t just about clothing. Keep moving. When conditions allow, stand up, stretch your legs, clap you hands, coil some rope, check sail trim. In the fight against cold, your hands are tied if you’re sitting still. Keeping busy can also help stave off seasickness.

Air leaks. As it grows colder, air leaks matter more than insulation. Separate jacket and pants allow helpful ventilation in mid-range temperatures. This exchange of air keeps you warm by preventing condensation that will make you colder when temperatures drop. In near-freezing temperatures, however, one-piece outer layers are more efficient than two-piece, jacket and pants. Colder temperatures mean drier air, so the chill, rather than dampness, is your chief enemy. Even in the rain, 32F air has only 10 percent relative humidity when warmed to 80F within your clothing. Yes, you still need ventilation, but you must be able to control it.

Full coverage. More insulation on your core is less effective than coverage from head to foot. A hat conserves more BTUs than adding a second sweater. A fleece layer on your legs adds more warmth than a third top layer. Learn to work with gloves. Dress evenly.

Head gear. Wearing a hat is not about just keeping your ears warm. Cape Horn navigator Skip Novak likes his Andean chullo in alpaca wool. High-latitude racers prefer water-repellent synthetic balaclavas made for sea-kayaking. These keep your head dry and seal the neck against drafts. You can wear a ball cap over it to help retain the hood, or a fleece cap if it is really cold; the balaclava helps keep other hats in place.

Eye wear: It’s not summer, but you’ll still need eyewear. Ski goggles help warm your nose and cheeks by keeping the top half of your face warm. Look for bronze, polarized lenses, which offer an effective combination of UV protection and ability to cut surface glare, even in low light.

Gloves. Sailing gloves are fine for summer, but for winter you’ll want better repellency and insulation in your winter sailing gloves. And because work like hauling anchors and mooring lines can tear up more comfortable insulated gloves worn on passage, you’ll also want some heavier work gloves.

High-gauntlet PVC gloves used by Alaskan fishermen are inexpensive, dry, and relatively durable, but they are only as warm as the inside liner. Some sailors also like these gloves for the helm, but they are bulky and hard to use when handling lines or winches. Knit freezer gloves, with only the fingers and palms coated get soaked easily, but they dry fast and are good choice for hauling on cold, wet chain or rope.

Gore-Tex ski gloves can do well, though most can’t repel constant soakings and are hard to dry. Two-piece systems, incorporating an insulated outer shell and an inner liner, are popular with mountaineers because they are easier to dry. A leather or rubber-faced liner that doubles as a glove can be quite handy in severely cold weather. You can remove the insulated layer, and wear only the liner for tasks requiring better dexterity.

Neoprene dive gloves (3 millimeter) are warmer when wet than most winter sailing offerings, but they don’t hold up to rope handing. Waterproof, they are a good choice for long nights at the helm. Whatever gloves you choose, don’t forget spares.

Room for socks. Whether you’re wearing boots or deck shoes, cold toes can bring misery. Footwear for the winter season should be a larger size than summer wear. For winter sailing, we often wear a drysuit with neoprene dinghy boots, leaving enough room in our boots for both the drysuit-feet and a pair of fleece socks. We also have a pair of deck shoes that are a half-size larger for wearing with fleece socks in cold weather.

Seaboots. Boots for winter should have room for a liner sock and two pairs of fleece socks. Comfort is important. For occasional cold-weather sailors with a tight budget, light duty, Gore-Tex-lined hiking shoes with non-marking soles can make good cold weather footwear. For wetter offshore conditions, you’ll want good sea boots.

Windsuit or soft shell. Non-waterproof shells breathe far better than heavy rain gear ever will. A lightweight water-repellent wind suit (top and bottom) takes no space, dries instantly, and is comfortable when working hard in dry weather. With the right inner layers, this light suit can also provide adequate protection in colder temperatures-provided it’s not too wet.

LAYERING

An insulated jacket is handy for spring and fall sailing, but for multi-day cold weather trips, the insulation will become progressively sodden even if it doesn’t leak. When moisture leaves your skin it is transported outward until it reaches a surface that is below the dew point. In a fleece-lined nylon jacket, this is the inside surface of the outer shell. This moisture will condense on the inside of the jacket, often convincing the wearer their expensive coat is leaking, though it actually is not. Separate layers can prevent this build-up, and if the inner layer becomes wet, you can more easily dry it out. An insulated jacket, on the other hand, will gradually become sodden, not drying until you get home.

Shed layers. There is no combination that will keep you warm when sitting and sweat-free while working. Open a vent, zip open a shell, remove a layer—all of these are options depending on conditions. Sometimes the easiest option for a short task is to take off your hat; your ears might get cold, but you won’t overheat.

Odor control. Smelling nice is less important that staying warm, but if you can keep the boat odors tolerable, it will make life more pleasant for everyone on board. Many synthetics are treated with anti-bacterial treatments claiming to control odor, but in our experience the treatments fade after a season of washes.

Typically, the odor is most severe where clothing touches skin. Synthetics for socks, base layers, and all mid-layers will help keep odor at bay. A top undergarment of merino wool also helps control odor. For the low-budget daysailor who wants to control odor, cotton tee shirts will work just fine as an underlayer—despite what all the experts say. They will also insulate well on dry days, but the insulation value is next to nothing when wet.

Stay dry. One main problem with wool is that it takes much longer to dry. Our testing with socks (PS November 2008) tells us that the wool insulates, wet or dry, but dry is always preferable to wet. Cotton is a terrible insulator when wet.

Durability. Wool insulates, but it doesn’t match synthetics against abrasion. We’ve had safety harness straps wear right through a wool pullover. Expensive wool socks won’t last long unless they contain about 15 percent synthetic fiber for reinforcement, but more than 25 percent synthetic effectively negates the insulating properties.

WARM AND WET

Invariably, a cold-weather sailor will be caught out in wet and cold conditions, and not have the opportunity to change into dry cloths. This is why synthetic mid-layer materials that dry quickly with body heat and still provide warmth are essential. This is not the most comfortable tactic, but it works. In the case of mid-layers, a synthetic fleece blend is the economical, practical choice. Wool takes too long to dry. Synthetic base layers are also preferable for the same reason.

No jeans or cotton sweatpants. Although cotton underwear can be used in cold weather, cotton is a poor choice for outerwear—and certainly anywhere you will get wet. Denim and cotton pile lose all insulation value when wet, and they are very slow to dry. Cotton sweatsuits can be nice for evenings and sleeping, but they must be kept dry. We like cotton sheets, but most of our blankets are synthetic. Sleeping bags should have high quality synthetic insulation. Dampness and down don’t mix.

Mid-layers. Our favorite mid-layers are synthetic and wicking, for these can be worn on their own, serving double duty. Soccer training pants and fleece pants both make excellent mid-layers and can even be worn to a casual dock gathering. To keep the knees from wearing through, you can put knee pads over them (see PS August 2018). Some soccer goalkeeper pants already have thin padding on the knees and hips that will stay in place. These garments wick perspiration well and dry very quickly.

Top mid-layers are fleece jackets, with an emphasis on a long, slender torso and good freedom of movement in the shoulders. Sailing gear works great, but there are often less expensive options available through mountain outfitters. The needs of mountaineers and other sports are virtually identical to those of sailors.

Diaper cream. Cold and dry weather can cause the skin to chap, peel, and crack. Applied liberally to face and hands, a zinc oxide cream like Desitin will prevent chapping. There will to be times when you can’t get warm and dry, and can’t face a shower or even sponge bath. If you don’t do something to protect your skin, it can chap and chafe, making for a miserable passage.

PROFESSIONAL KITS

Foul weather gear for tough ocean conditions in cold waters demands incredible durability, functionality, water tightness, and breathability. Expect to spend a lot for a good set, upwards of $1,000. Start with a three-layer Gore-Tex laminate. The fabric is heavy, stiff, noisy, and quite durable. Lightweight gear often uses a two-layer breathable system, but the thin inner liner is vulnerable to internal chafe. Some styles of pants and jacket are protected by a loose internal liner, but this liner slows drying, makes clothing frustrating to put on wet, and is fragile. Look for wear patches on the knees, seat, and elbows.

Keep wind out. Water- and wind-tightness are a must. Adjustable neoprene wrist and neck seals reduce water ingress, though not as completely as a drysuit. A snug bib, with elastic or an adjustable internal belt helps keep drafts out. A high collar and hood that moves with your head is vital to ensuring good peripheral vision. Pockets are valuable, but some designs are less useful than others (see PS, February 2015).

DRYSUITS

For prolonged cold ocean sails, it is hard to beat a drysuit. Fabrics and construction are very similar, generally with fewer pockets and no hood (some have hoods). Water tightness is complete, providing better protection from hypothermia if you go overboard. Tech editor Drew Frye once spent 6 hours in 32F water (US Coast Guard standard for an immersion suit) in order to test drysuit performance compared to that of an immersion suit that meets the USCG standard.

Look for styles that focus on watertight integrity and function rather than pockets and gadgets. The down side of a drysuit is reduced breathability, limiting its use to temperatures below 55F unless it is very wet. Fitting can be difficult for people outside typical athletic body size and shape.

Good seals. Tight seals at the neck and wrists are essential for good drysuit performance, but seals with rough seams that pinch can be irritating over the long haul. In really wet weather, bad seals will lead to the slow drip-drip of water down the neck, or the sudden rush of ice water to the arm pits when you reach up. For this reason, we like dry suits for extreme conditions and even sustained cold rain.

Traditionally, dive suit seals were black latex and were always supplied too tight, with tapered openings that the wearer could trim to fit snugly, but not too tight. Some drysuits are now offered with adjustable, Velcro cuffs and seals. Although we’re sure these will work for some people, we prefer simpler latex seals, the same material used in the suits preferred by most Volvo sailors.

Although quite thin, the latex material is very stretchy and provides a perfect seal with minimum pressure. Compared with scuba dry-suits, which are very snug at the neck and cuffs, sailors require only minimal pressure- enough to keep out the rain and prevent leaks while swimming on the surface.

To ensure the right fit, wear the top of the suit for a few days to break in the latex seal, then store them for a few weeks with something relatively large stuffed in each opening (a two-liter soda bottle fits the neck and smaller sports bottles will fit the wrists), and then trim very carefully along the provided guidelines with sharp scissors. If the seal has been trimmed correctly, you will hardly notice the seals after a while. Someday they will tear, but they are not difficult to replace.

Reinforced latex. Reziseal, a type of reinforced latex used at the seals of Zhik dry suits and others, offer the promise of longer life, but at the cost of reduced resilience and a less watertight fit.

Adjustable neoprene. Similar to wetsuit material but thinner, adjustable neoprene seals last longer than latex, but they are less comfortable unless fitted so loosely that they leak just a little. They generally last the life of the suit, but are not easily replaced or repaired.

Foulie fit. Fit is essential for foul weather gear. First, make sure the underlayers and accessories fit first; you’ll need to wear all of these when you try on foul weather gear. You will also need to try the gear wearing only the T-shirt and shorts you’ll wear in warmer weather.

In cold weather, baggy isn’t warm at all, but in warmer weather you need room for air to circulate. The pants must not grab at the knees (a fault in loose pants as well as tight) nor hang down at the crotch or puff out at the hips. You must be able to reach and stretch without binding, and the hood must fit well enough to turn with your head.

Although oversized clothing will never pinch or bind, it is prone to snagging, gets in the way, is cold, and will slow you down. This is an important justification for close-fitting under layers accessories; the slimmer the fit under the suit, the less need for excessive bagginess.

Dry suit fit. To check fit on a dry suit, squat in a tight ball before zipping the last inch to expel excess air; this is how they are worn. A drysuit typically fits more closely than traditional foul weather gear.

PFD and harness.Your PFD/harness or harness must have enough adjustability to fit you well while you’re wearing a T-shirt, and while you’re wearing full winter gear. Crotch straps are required; no matter how tightly you wear your PFD or harness, they will slide.

| Cold Weather Clothing Price Comparisons | |

|---|---|

| Mainstream foul weather gear | |

| Helly Hansen HP Foil | $400 |

| Cyclone Light Jacket | $80 |

| Pier 3.0 Coastal Sailing Jacket | $259 |

| Zhik Isotak 2 Smock | $779 |

| Gill OS2 Men's | $375 |

| Grunden Superwatch | $115 |

| Hooded Anorak | |

| Drysuit | |

| Gill | $645 |

| Atacama Sport Sailing | $359 |

| SEAC | $1,349 |

| Shik Isotak X Drysuit | $699 |

| Racing Foul Weather Gear | |

| Musto HPX Pro Ocean Smock | $1,500 |

| Musto HPX | $1,800 |

| Zhik Isotak 2 | $799 |

| Gill OS13 Ocean Jacket | $650 |

| Base Layer | |

| Nike Dri-Fit Player Shirt | $84.97 |

| Nike Dri-Fit Pants | $90 |

| Diadora Padova Pants | $49 |

| Mid-Layer | |

| Marmut Reactor Fleece | $105 |

| Bluesmith's Kula Hoodie | $275 |

| Gill Thermogrid Fleece | $69.99 |

| Flotation Suit | |

| Fladen First Watch | $499.95 |

| Mustang Survival Anti-Exposure | $689 |

| Accessories | |

| Uline Freezer Gloves | $75 |

| Smith Anthem Ski Goggles | $49.99 |

| Chulla Hat | $60 |

| Kotat Surfskin Balaclava | $40 |

| Sealskinz Socks | $43.61 |

| Smart Wool Crew Socks | $16 |

Tailor for the boat. Not every boat is a canting keel ocean racer, playing submarine and exposing the crew to frequent green water on deck. On a boat with a hard top, enclosure, or large dodger, you can stay dry and warm in some particularly rough conditions, but its better to be safe. The deck watch should always be prepared for prolonged exposure on deck in an emergency.

WORKBOAT FLOTATION SUITS

Beyond the realm of yacht wear, there are many options.

Fishing Rain Gear. Many sailors wear Grundens, a popular brand among commercial fisherman. These kits are durable, absolutely waterproof, but a little stiff and lacking the refinements of foul weather gear costing five times as much. The hoods are less functional, neck and wrist seals are lacking, and they don’t dry fast. That said, with the right layers underneath, this gear is well proven in cold waters.

Flotation suits. No to be confused with immersion suits (see Immersion Suit Test, July 2007) which anticipate going in the water, flotation suits are insulated, one or two-piece suits designed for occupations where going overboard is a very real possibility. Numerous European companies make them, and some are available in the US (look for those certified under ISO-15027-1 and EN 393). These typically provide less flotation than a PFD, but if you subtract the weight of the foul weather gear they replace, the difference is minor. They won’t turn a swimmer face-up, though some have inflatable head rests.

As with a dry suit, flotation suits provide protection from hypothermia, allowing a person wearing one to survive several hours in cold water without succumbing to heat loss. They are waterproof, provide insulation even when wet, and, importantly to Baltic fishermen, they cost far less that top-of-the-line dry suits or foul weather gear.

On the downside, they are bulky, and if the air temperature rises above about 50F an active person will sweat profusely, since there is little way to reduce the insulation value. Some are only listed as flotation aides, leaving the question open as to whether to wear a PFD as well.

The target market is primarily fisherman and commercial boaters in the North Sea and Baltic Sea, where cold water and gloomy days are a year-round reality. A harness and tether makes no sense for fishing or working commercial shipping, so falling is a constant possibility.

A flotation suit will keep you warm and dry in extreme conditions, but for sailors, it is less practical than layering with a drysuit. The prevalence of drysuits among Volvo racers confirms this wisdom. Price is a consideration. Drysuits range from $750-$2,100 versus $175 to $480 for an flotation suit.

COST

As you can see by the cost comparison table (updated September, 2024), some of the name brand items on the list are pricey. However, through a mix of thrift shore and non-marine shopping, you may be surprised how far the dollar can stretch. With the exception of a drysuit, you can put together a winter outerwear ensemble for coastal sailing for less than $500-sometimes much less. A few proven ways to reduce the sting:

Ugly fleece is just as warm as pretty fleece. Look for a slim fit that offers full range of motion and can serve double duty as cabin wear and pajamas. Second hand stores in ski country usually abound in good used uppers.

Search for discounts. Last year’s model is often as much as 40 percent off.

Don’t scrimp on footwear, gloves, and head coverings. These represent your contact with the boat and surroundings. They also offer the best BTU/pound savings. More fleece for your torso and legs is cheap.

Choose between a heavy-duty foul weather gear or drysuit, but probably not both. In our view, there should be at least one drysuit on board for in-water emergencies, but most boats don’t require such extreme protection, even in nasty weather. Medium weight foul weather gear is more comfortable and will be durable enough. Choose bibs over pants.

CONCLUSIONS

As much as we’d like to offer a single recommendation, all of the sailing gear is well proven. Commercial gear from Mustang, Fladen, and Grundens offers a lower cost alternative that may or may not meet your cold water sailing needs. Choice boils down to budget, needs, and personal preference.

Test the underlayers and accessories first. How they fit your body both alone and under your foul weather gear is important. Go sailing deeper into the fall, using whatever outer layers you have, remembering that air leaks matter. If your feet are cold, the problem may be your hat or your legs. Only after you’ve figured out what it takes to stay warm all day, through a variety of activities, are you ready to look at the pricey stuff that keeps you dry.

Consider a drysuit as an alternative to foul weather gear in cold conditions. Although drysuits are less breathable, they make agile deckwear in tough conditions, with unbeatable waterproof protection and warmth. They offer superior hypothermia protection in case of immersion, making them vital for kayaking, dinghy rides in rough water, and for in-water access to inspect the hull and untangle fishing gear. In very cold water, you need either a drysuit or immersion suit for each person, and a drysuit offers an opportunity to save duplication. Pair this with lighter coastal-weight foul weather gear for less demanding conditions.

The boat type (is your helm protected?) and expected conditions will likely determine how much you spend. A full kit, top-to-bottom for extreme conditions can cost more than a thousand dollars, but for most sailors, smart layering you can keep you warm and dry for a fraction of that.

In milder conditions, lighter coastal racing gear is suitable outerwear for more limited exposure (good wrist and neck seals are still important). A drysuit can be reserved for kayaking, dinghy rides in freezing water, and of course, the most horrible days underway.

If you’re headed for higher latitudes, comfort is critical, because the best gear is useless if you don’t wear it. While on watch on long passages, you’ll want to be fully dressed or nearly so, ready in case an emergency requires your attention on deck. In heavy weather, the off-watch crew might also need to be dressed and ready. We’ve spent many long nights sleeping during the off-watch in bibs, or even full foul weather gear.

We’ve done a number of tests on cold-weather sailing apparel, keeping track of the many innovations over the years. While many sailors focus on the big ticket items, often it is the less expensive accessories like hats, gloves, and undergarments that determine comfort when the going gets tough.

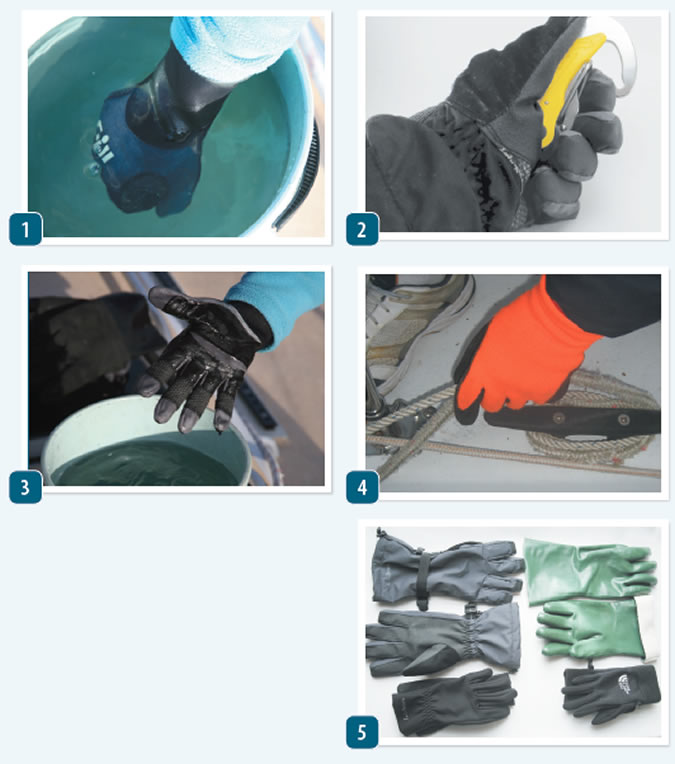

1. A ball cap under a balaclava provides warmth and sun protection. Look for our report on headwear for sailors in an upcoming issue.

2. Glove liners under neoprene Glacier Gloves offer excellent warmth and protection against the wet. The only drawback to neoprene is that it can take longer to dry (see PS November 2008).

3. Fast drying base layers are a first step to keeping out the cold (see PS January 2006).

4. Mustang’s tightly sealed drysuit takes the chill out of 40-degree Lake Superior. Less expensive brands have also proven effective in our tests.

Fit is extremely important when it comes to gloves. Most on deck tasks don’t require fingertip control, but you need to be able to operate locker latches, grind winches, and handle lines.

Over the years, we’ve tested a wide range of gloves. Unlike some other apparel categories, brand-name sailing gloves are not significantly more expensive than comparable gloves designed for other commercial or outdoor pursuits.

1. A Gill neoprene winter-rated glove undergoes an immersion test for our report on cold weather gloves. Only two pairs we examined passed this test.

2. Dexterity is important, especially for deck crew. Check that you can operate small actuators, such as winch handle releases, or latches on snap hooks (shown here).

3. Coated-palm freezer gloves have excellent insulating properties, dexterity, and durability, but they get soaked easily. We keep extra pairs for handling muddy anchor chains and dock lines.

4. Inner and outer gloves offer flexibility and dry more quickly than thicker, heavier insulated gloves. Liner gloves with reinforced grips can also be used alone in moderate conditions.

living/ sailing in bc we cover all range of weather… my choice after a few experimental winters was

silk long underwear…. wool trousers and fisherman’s sweater… dry days wool jacket… and heavy wool socks the longer the better wet days (if necessary)

gortex… (or a guest)…. never had much luck with footwear though a good pair of hiking boots worked well..

For my hand I love my kevlar re-enforced dive gloves. Extremely warm, great wear resistance, and good dexterity.

Blew your credibility when you said cotton is ok for under layers. It just isn’t adequate for cold or damp.

Thanks Jim. I could see how the comments under “odor control” could be misunderstood as referring to insulation properties. The good for “most days” referred to odor control properties. I’ve made that clearer now. In terms of insulation, as our testing of other sports undergarments—especially socks—indicates, cotton isn’t such a bad insulator when dry, but, as you point out, it is a terrible insulator as soon as it gets wet. The report’s text inferred this “cotton pile makes a terrible insulator,” but I’ve now also emphasized this point to make it clearer.

As our recent sock report

https://www.practical-sailor.com/personal-gear-apparel/wool-sock-update

stated:

“Not surprisingly, the data show that cotton is a fair insulator when dry, but when it is wet it performs little better than wearing nothing at all. That squares with our experience.”

“Our experience” in this case includes many, many, hours of field testing by our tech editor and avid winter sailor, and ice climber Drew Frye. His reports have helped re-shape many current products used by sailors, and informed ASTM testing. Most experts regard him as highly credible. We’ve now corrected the article so as not to leave anyone else with the wrong impression.

I rode a motor cycle from Omaha Nebraska to Abilene Texas in February temp 5 deg F take my word for it. It is much better in my opinion it is much better to be dry and a little cold than warm then sweating and

then really cold , when it’s 80 deg F at 60 mph it’s cold when riding for several hours.

Very good article! Thank you!! Shout out to ski goggles. Also, ice-climbing gloves tend to be designed with desiderata we like: toughness, dexterity, effectiveness in cold wet environments. Those under a pair of easy-to-remove shell mittens can be versatile.

We all care about different things. I am happy to dress for cold and work with some physical discomfort, but living in a space that reeks of sweaty polyester takes an enormous amount of fun out of it: why go to the trouble to be near nature if I can’t smell nature? To say nothing of putting effort into brewing good coffee and still not being able to taste anything other than stale sweat 🙂 No synthetics on my boat! For anyone who feels similarly, don’t let Darrell talk you out of sailing in the cold. Wool can be very very good! It doesn’t dry quite as fast as synthetics, but several thin-to-moderate layers dry sufficiently quickly. The trade-off might be bringing an extra set or two. In the worst case synthetics might give you a little extra leeway, but many people with a cabin heater and a space to hang things will be fine. I was finding that a 150-weight t-shirt, 2 or 3 200- to 300-weight shirts, and then a more traditional heavy wool sweater (+ waterproof shell, of course), kept my torso happy. Similar regimen for the lower half, although I wish I had a source for what were the world’s best adventure pants: the old Ibex Gallatin. There are a dozen good sources of socks, and I mostly wear a lot of Darn Tough, but if you can afford sailing or even just winter camping, I’ve found that a pair or two of Dachstein socks have a higher benefit/cost ratio than most of my kit.

Possibly another reason for wool: Everywhere—even the polar regions and the last remaining glaciers and the deepest ocean trenches—is covered in microplastics. The cold tourist regions are covered in fleece dandruff. It’s a drop in the bucket, and the ocean dilutes this pollution source, but is that good? I hesitate to mention it because I know that spending effort on individual ethical decisions takes mental effort away from demanding change to pollution-control policy, which is a much more important place to spend energy. But perhaps more demand for adventure wool in a capitalist system pushes on some feedback loops…? So I’ll just leave that there 🙂

A few years ago Backpacking Light magazine reviewed waterproof-breathables. For their purposes, the direct-venting stuff (e.g. eVent) was dramatically better both in theory and in the real world than the best Gore-Tex of the era, and that has been my experience as well—enough so that it made sense to compromise considerably on design to get the better fabric. But Gore-Tex is far more heavily marketed. What’s the scoop for sailing-specific gear? Effectiveness in salt water, etc?

Speaking of waterproof-breathables: there are WPB drysuits, and even divers are talking about them. I have a paddling jacket that uses one, and it’s dramatically better than my old non-breathable one in some weather. Seems like this should be high on the list for a sailing drysuit, but I’ve never tried one of the real ones. Thoughts?

Thanks again for all the great info!

I usually agree with your tests and recommendations, but not this time.

As a long time all year sailer in the Pacific Northwest , British Columbia , we have developed a pretty much foolproof system to stay out in around freezing or just cold and rany temperatures. This system is good for a 6 to 8 hour day mostly outside .

We have floater suits . We would use them to abandon ship , not to keep warm . They cannot keep us warm for long. If a suit restricts air flow too much , it becomes wet from the inside out . Your insulation , what little there is , becomes wet and decreases it’s effectiveness.

This is what we have found most effective for foul cold weather . And it effective for multi day trips .

Wool long underwear , top and bottom . Merino wool is soft and not scratchy.

Wool work shirt and pants .

A wool sweater .

Down pants and coat .

Oil skin tops and bottoms such as Helly Hanson Storm Suit , a size larger then usual to accommodate the down clothing .

Heavy wool socks .

High top felt pack rubber boots . Baffin makes a good set about 13″ high . Get a good set of arch supports and try them on with the arch supports in and heavy socks on . They should be loose , as all of the gear above should be . You are not going hiking , mostly standing around .

A wool scarf .

A heavy souwester rubber hat that will fit over a wool balaclava .

With this set up you will keep dripping and most blowing water out , except blown into the face and dripping down the neck . A wool scarf will limit that . The oil skins will allow enough air flow to take away most of your body moisture.

This gear will all dry out overnight , or during your off watch , if you have anything near an adequate heating system for the purpose .

It is not a cheap system , but it is not all that expensive either . It is durable and needs no short term maintenance. Most of the stuff can be bought at a good work wear store .

I really cannot see the recommended gear in the article keeping a person warm for a long winter day , let alone a long , wet winter day . Our system has kept us warm and happy for many weeks of often wet winter sailing .

Love your magazine. Keep up the good work .

Great article on an important topic.

I totally agree with comments regarding the utility of wool, having recently completed a week long passage in the Southern Ocean and been amazed at how well wool kept me warm. A merino wool singlet, long sleeved merino wool T-shirt with a zip up polar fleece sweater and wool undies and long johns under my offshore wet weather gear during the day. At night an extra T-shirt and cotton tracksuit pants. I will admit the cotton would have been pretty useless if it had gotten wet but I only ever wore it under foulies & over wool longjohns so it served. After wearing the singlet l/s tee and long johns for a week, they simply didn’t smell. My usual smellometer (the missus) asked if I’d actually worn them!

The merino wool, wonderful as it was, did need to have been washed a few times to make it soft enough to not be a bit prickly for some.

The other point to strongly reiterate is the importance of activity. It is so easy to find something to do like coiling a rope and it makes a great difference. And wear a hat, any sort of hat!

This is an excellent article on cold weather sailing gear. For 30 years I have sailed and fished on Lake Erie, Lake Ontario, the Niagara River, and the Gulf of Mexico in cold weather.

I like my Mustang Deluxe Anti-Exposure Coverall (MS21750). It is warm, comfortable, wind proof, water proof, and a USCG approved PFD. On a few overnight sails in cold and rough conditions, I have slept in it. Cons are that it is bulky and it is not breathable.

I also recommend the Gill Helmsman Sailing Gloves. They are insulated, waterproof, and have a large cuff. They can be used on a touch screen. They are curved and comfortable to wear for long periods.

I also recommend the Sperry tall sailing boots with warm wool socks.

What nobody has mentioned yet is that as soon as you get sealed into your warm dry gear you are going to want to pee. Although peeing in your suit may give you a warm feeling for a short time, easy access for peeing is a better solution. What’s your best recommendation?

The dry suit I have (Ocean Rodeo) has front and rear access, so no problem. However, taking it off is probably more reasonable for rear access. That’s nearly true of most heavy rain gear.

Hi Darrell and all,

I have done a moderate amount of higher latitude sailing and tend to push the ends of the seasons and most of the advice rings true, but one thing left out is the importance of being able to heat the boat. Even with the best gear, it is possible to get a chill when, say, on watch for a period of time with little to do.

And, generally said, one makes better decisions and executes those decisions in a safer manner when one’s core is warm.

On Alchemy, a 40-foot sailboat, we have an Eberspracher forced air diesel heater (for underway) and a drip diesel Refleks for at anchor. Even when only bringing the inside boat 15-20 degrees above outside temperatures, this increase in temperature is a big benefit: you wring out the moisture a bit, you can strip off a couple of layers making cooking easier, one’s outside top layers have a chance to air out and dry and be more appealing to put on when the time comes, etc.

I consider the ability to get warm in cold conditions a safety issue as bad decisions get made when one is cold. And, we do not have to be in higher latitudes to get cold: one can get plenty cold on a windy and damp 60-degree day on the water.

My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Re. Odor and the wool vs. synthetic debate, it’s a real conflict. No question.

Personally, I don’t like the feel of damp wool against my skin, and it always gets dampish eventually. This includes the most modern soft products. This is personal. I don’t like that wool takes about 30-100% longer to dry, depending on the conditions (the great the humidity the greater the difference, since it takes more energy for wool to desorbe water). Others may feel the opposite, so only personal experience and preference matters in the end.

I don’t like the smell of polyester, at all. Polyolyfins are even worse, so I have none of that in my wardrobe. Goo products come with an anti-stink treatment, often silver-based, but it only survives about a dozen launderings. One solution is to wear a cotton tee shirt or turtle neck underneath. Yeah, the outward bound leader told you this would kill you, but (a) you shouldn’t get that wet and (b) you are on a boat, not back country, and you can change. I don’t favor the cotton turtle neck because they wick up the sleeves too easily. I always have cotton for cabin wear; again, it’s just more comfortable. One a multi0day cold season trip, the tee shirts progress from cabin wear to underlayer, and so there is always a fresh cotton layer for cabin wear.

Legs don’t pose the same problems for me. Fleece is fine, with soccer training pants being my favorites, because they serve so many purposes (cabin, around town, insulating layer, even sleeping). I’ll have a few pairs.

I think the main thing is practice. Learn what works for you in terms of comfort, drying, stink and so forth.