Perhaps nothing on boats has developed as steadily and soundly as line-holding devices—cams, clams, jams, clutches, stoppers and plain old horned cleats.

There were some dismal failures along the way. However, keeping pace with the never-ending improvements has been a pleasant pursuit for Practical Sailor .

One of the most important PS reports was the August 1, 1992 slippage and strength tests done on 16 varieties of cam cleats. We cranked most of them up to 1,000 lbs. Found best were the Harken Cam-Matic, the Holt-Allen, the Ronstan C-Cleat and the Schaefer Sure Grip. The carbon-fiber Ronstans were the Best Buy with Harken close behind.

Clutches were most recently evaluated in the May 1, 1996 issue. Lewmar’s Superlock was the winner; Garhauer was the Best Buy.

Another major report was the August 1, 1997 tests, which involved nearly two dozen different line-holding devices. The intent was to cleat and uncleat a line thousands of times to see which device best resisted wear. The winner was the Clamcleat™, with all clam-type devices being easier on the line. Of the cam cleats, the Ronstan C-Cleat (the Best Buy) and Harken Carbo-Cam best resisted wear, both on the device and the line.

Boat owners know that the danger when using these cleats is that if the line tension increases (after the line has been cleated) it may become impossible for one person to free the line by hand, in which case a winch (or a knife) becomes necessary.

A cam cleat that attempted to deal with the problem was the very well-made Nash Trigger Cleat, invented by a Californian named Douglas B. Nash. A line could be released or adjusted by pulling down on the line against a protruding lip that operated a rocker arm that opened the cams. Our test (in the June 15, 1993 issue) of the Trigger Cleat indicated that the line could be released up to about 220 lbs. That was some help with the problem. However, pulling down on the line was not always possible. A new cut at a solution was introduced recently by Spinlock, the British company that bills itself as “the experts in rope holding.” The new cleat is called a PX Power Cleat. It’s made largely of carbon fiber, with two stainless axles, three springs and two ring-like inserts to reduce wear from rope abrasion.

Using a single serrated cam against a curved serrated base (which gives it a large gripping surface), the PX has slanted ridges on the movable, hinged housing that, when lifted up by the line, act to move small wheels on the ends of the cam axle and swivel the cam up and away from the line. When the line is lowered, the spring forces the cam back down to grasp the line.

Spinlock calls the cam mechanism “Rolacam” and has applied for patents. It is ingenious engineering utilizing some interesting geometry.

How well does it work?

We mounted one of each size, and jerked them around unmercifully over several weeks but could not induce a malfunction of any kind. As stated by the warning on the package (which doubles as a drilling template), you don’t want to have your fingers close to the PX when you lift up. This is true of any device holding a line under considerable tension.

The PX comes in two sizes—for 4-6 mm (5/32″-1/4″) line and 6-11 mm (1/4″-7/16″) line. The small version ($26.50) has a safe working load of 140 kg (about 300 lbs.) and a breaking strength of 280 kg (about 600 pounds). The large version ($30) goes 200 kg/440 lbs. and 400 kg/880 lbs. The strengths are roughly equal to Harken cams and Ronstan C-Cleats.

They are available in singles and doubles, with optional wedges, adapters for block arrangements and, for those who like color coding, have easily installed inserts in red, yellow and blue. The cam, if it wears, can be replaced easily. (Spinlock USA/Maritime Supply, 12 Plains Rd., Essex, CT 06426; 860/767-0468.)

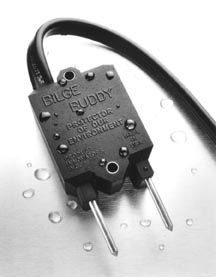

Electronic Bilge Pump Switch

The ubiquitous bilge pump switch is one of those things that seems simple in concept, but is difficult to implement in a reliable design. All of us have suffered from jammed, failed, or broken switches. Sometimes we get lucky and it happens while we are onboard to correct the problem. Other times, a broken switch can literally sink your boat. One friend’s boat sank when the wine cork replacement float on the bilge pump switch jammed on, leaving the pump on constantly on a leaky wooden boat, thereby draining the battery.

The bilge is one of the more inhospitable places on the boat to place a sensor. There have been numerous designs used for automatic bilge pump switches—floats connected to switches, air pressure changes caused by changing bilge water levels, and optical sensors looking at light attenuation. All have their strengths and weaknesses, and it is a fallacy to think that any one sensor will always work in the miserable bilge environment.

The Bilge Buddy from Product Innovators, Inc. addresses the automatic bilge pump switch in an electronic fashion. The Bilge Buddy is encapsulated in a black polyurethane casting with two brass prongs protruding from the bottom of it. The main body of the Bilge Buddy is 2.93″ H x 2″ W x 1.1″ D. It appears to be well-sealed. The prongs protrude 1″ below the bottom of the case. It has two brass bushings through the case that will accommodate #10 mounting screws (not supplied). Coming out of the top of the case is a 1 meter 14 AWG 3-conductor cable with prestripped ends. The brass prongs have a thin acrylic coating to retard corrosion. Caution: The acrylic coating is easily scratched and will breakdown in UV light (not that the light ever shines in our bilge).

The Bilge Buddy uses the conductivity of the bilge water to actuate an internal relay. When the two prongs have connectivity because of water (or tools or a sweaty arm), the relay connects the boat’s battery positive terminal to the bilge pump. Oil, diesel, kerosene, gasoline, and distilled water do not have enough conductivity to trigger the switch. If the fluid is not conductive, then the Bilge Buddy will not energize its relay. For example, if there is a significant oil layer on top of the bilge water, the Bilge Buddy will not energize the pump until the water level rises enough to contact the prongs.

For testing purposes, you can also actuate the switch with a wire jumper or screwdriver across the prongs. You can hear and feel the relay actuate, which will aid in debugging problems if they should occur. Once the water level drops below the prong level, the switch keeps the relay energized for an additional 10 seconds to add hysteresis to the system.

In our tests, the Bilge Buddy appears to work as advertised. We set up a 12V power supply, an oscilloscope, a DVM, and an AM radio and proceeded to learn about the innards. All the technical information came from this bench testing, including the relay resistance measurement. We also tried to “trick” the Bilge Buddy by using a piezo lighter near it, hoping that the spark would trip the relay on. On the good side, we couldn’t find any electrical way to trick the Bilge Buddy into an on state.

After the bench testing, we set up an experiment to check the Bilge Buddy’s conductivity sensitivity. We tested the following liquids:

Switch closed relay: tap water, saltwater, milk, coffee.

Switch did not close relay: distilled water, oil, gasoline.

We then checked a mixture of oil and water. We slowly lowered the prongs into the oil. When the prongs broke through the oil/water skin, the Bilge Buddy energized the relay.

We also tested with bilge cleaner mixed with water because other conductivity switches we’ve tested in the past have retained a residue on the sensors and continued to run the bilge pump. Repeating the test with the Bilge Buddy, it turned off the pump after 7 seconds, which we deemed acceptable.

The electronics within the device draw a constant 8 milliamps (mA) at 12 volts while in standby (less than 0.2 amp-hour a day). While energized, the switch draws 73 mA. The relay’s contacts have 0.040-watt resistance. A pump that draws 12 amps will develop a 0.5V drop across the relay, thereby slightly reducing the amount of water discharged by the pump. The switch will handle up to a 20-amp load. The switch is also available in 24V and 120VAC to 240VAC.

The Bilge Buddy comes with a seven-year warranty and is available from West Marine and other chandlers for $39.99. (Product Innovators, Inc., Box 412, Mongaup Valley, NY 12762, 800/793-4122, 914/796-4526.)

Improved Hot Knife

It’s sometimes difficult to work for a publication that looks for flaws in marine products. Just ranking things good, better, best sometimes is not fun. Neither is saying something negative about a particular boat, whose owners, to a man, love them with a passion. It’s like telling a father that his daughter is ugly.

However, what balances off the negative is that there are not-too-infrequent instances where marine gear is improved because of what we do.

A year or so ago, a small chandlery item called attention to the Hot Knife™, a small, inexpensive line cutter fueled by butane.

We liked it, but said that we didn’t like the fact that the gas (and flame) didn’t turn off automatically when released, as in a cigarette lighter. It must be switched off. The risk was considerable that you might lay it down and forget that it was still going.

John Halter and Jim West, who thought up the Hot Knife and got it manufactured, wasted little time. They quickly re-designed, retooled and mailed off the new version. When you’re a small start-up company, you can do that.

The new Hot Knife is an improvement over the original. It has not only what used to be called a “dead man’s switch” but an off lock lever, too. In addition, they made the stainless blade swivel; it swings free, giving access to an exposed flame if needed for other purposes. (Butane burns at several thousand degrees.)

It still sells for $28.95, everything included. (American Business Concepts, 4400 Sunbelt Drive, Dallas, TX 75248, 800/877-4797.)

There’s one other thing that’s extremely enjoyable: Helping ingenious sailors get their ideas out of the basements and garages where the prototypes are cobbled together.

Calendar of Wooden Boats

Okay, most people have already bought their calendars for 2000, but in the event Santa didn’t leave one under your mast, may we mention Benjamin Mendlowitz’s 2000 Calendar of Wooden Boats. It’s one of our perennial favorites.

The 12″ x 12″ page format (12″ W x 24″ H open) features a different boat each month. This year’s selections range from the 55′ gaff ketch Owl; a Bahamian dinghy built by the Joseph Albury Boat Shop in Man-O-War Cay; Foto, a 1929 photo chase boat built for Morris Rosenfeld; and White Horses racing White Wings, two 76′ W-Class sloops designed by Joel White and built by the Brooklin Boat Yard and Rockport Marine, Maine.

The print job is very good; colors are rich and vibrant, which is especially appreciated when viewing the inside of a small shop (Albury’s) or when examining Aida’s brightwork (a 33′ 6″ yawl designed and built by Nathanael Herreshoff). Other shots are backlit, which creates that otherworldly look of quicksilver. As a gift, you just can’t go wrong with this calendar. Price is $14.95 plus $3 shipping and handling. Mendlowitz also sells note cards, T-shirts and several books he has illustrated. The 2001 calendar will be available August 1. (NOAH publications, Reach Rd., Box 14, Brooklin, ME 04616; 800/848-9663)